Through articles, lectures, and radio shows, the artist emerged as the most influential voice for the Theosophical Society in Canada.

by Massimo Introvigne

Article 2 of 5 (published on consecutive Saturdays). Read article 1.

From 1926 to 1933, Harris actively contributed to “The Canadian Theosophist,” Canada’s leading Theosophical magazine, and was involved in the activities and controversies of the Toronto Theosophical Society. The Toronto group maintained notable independence despite the conflicts that fractured the international Theosophical Society in the 1920s and 1930s. In 1895, Judge led most American members into a schism from the Theosophical Society, which had its headquarters in Adyar, India, after Blavatsky’s death, with Colonel Henry Steel Olcott (1832–1907) serving as President. Following Judge’s death in 1896, his American branch faced another schism, where most followed Katherine Tingley (1847–1929), the founder of the Theosophical community in Lomaland, California. A minor faction sided with Ernest Temple Hargrove (1870–1939), Judge’s former secretary.

Many members of the Toronto Lodge, who had historically allied with Judge, including Smythe and Mitchell, spent several years with Hargrove’s branch before rejoining the Adyar Theosophical Society in 1907. The Theosophical Society in Canada experienced significant turbulence. In 1924, just a year after Harris’ formal membership, what Canadian Theosophists referred to as “the split” or “the break” led to the division of Canadian members into two branches, both recognized by Adyar, referred to as the Canadian Section and the Canadian Federation of the Theosophical Society.

In 1926, “The Canadian Theosophist” unveiled a seven-week course by Harris on “Theosophy in Its Relation to Art.” In 1930, the artist contributed to the radio campaign organized by the Theosophical Society and was considered its most influential spokesperson.

A noteworthy incident illustrating Harris’ advocacy for Theosophy involves British Columbia artist Emily Carr (1871–1945). Harris not only helped elevate this relatively unknown local artist to national fame but also sought to pique her interest in Theosophy. Carr first met Harris in Toronto on November 17, 1927. The two maintained regular correspondence for several years, during which Harris asserted that Theosophy could enrich Carr’s life and artistic endeavors. Although Carr never renounced her Protestant faith, she regarded Harris’ views with seriousness and started exploring Theosophical texts. She came to believe that Theosophy encompassed aspects akin to Native American spirituality, a topic she had previously delved into passionately. In her paintings “Nirvana” (1928) and “Blunden Harbour” (1930), Carr expressed her deep affection for Native American culture through a Theosophical lens.

“Grey” (1931) was referred to as “the most Theosophical of her paintings,” depicting the emergence of divine light from the primeval darkness of a Canadian forest.

Lacking any Theosophical lodges in Victoria, Carr sought a faith she viewed as both Christian and similar to Theosophy: Unity School of Christianity, a loosely pantheistic group rooted in New Thought. Nonetheless, her involvement with Unity did not strengthen Carr’s dedication to Theosophy, and she continued to be suspicious of Madame Blavatsky’s criticisms of Christianity. In 1934, she noted in her journal, “Somehow Theosophy makes me shudder now. It was reading H. Blavatsky that did it, her intolerance and particularly her attitude to Christianity.” Ultimately, Carr destroyed her copy of Blavatsky’s “The Key to Theosophy” and told Harris she had chosen to revert to “the beliefs of childhood.”

Harris sent a polite answer, explaining that, as a Theosophist, he believed that “Christianity for the first three centuries was pure Theosophy,” but that later it had become corrupted. Harris also insisted that Theosophy “is not a sect as is Christian Science, Unity, or New Thought, or in the same sense. For it advocates the study of all religions, philosophies, and science. It is the synthesis of all these—that is what makes it difficult.” Carr was not persuaded. Later, she wrote that Theosophy “goes round and round in circles and makes you giddy,” and that it was “a sort of endless voyage with God always way, way beyond… without the love of a real Jesus Christ to bridge the gap.”

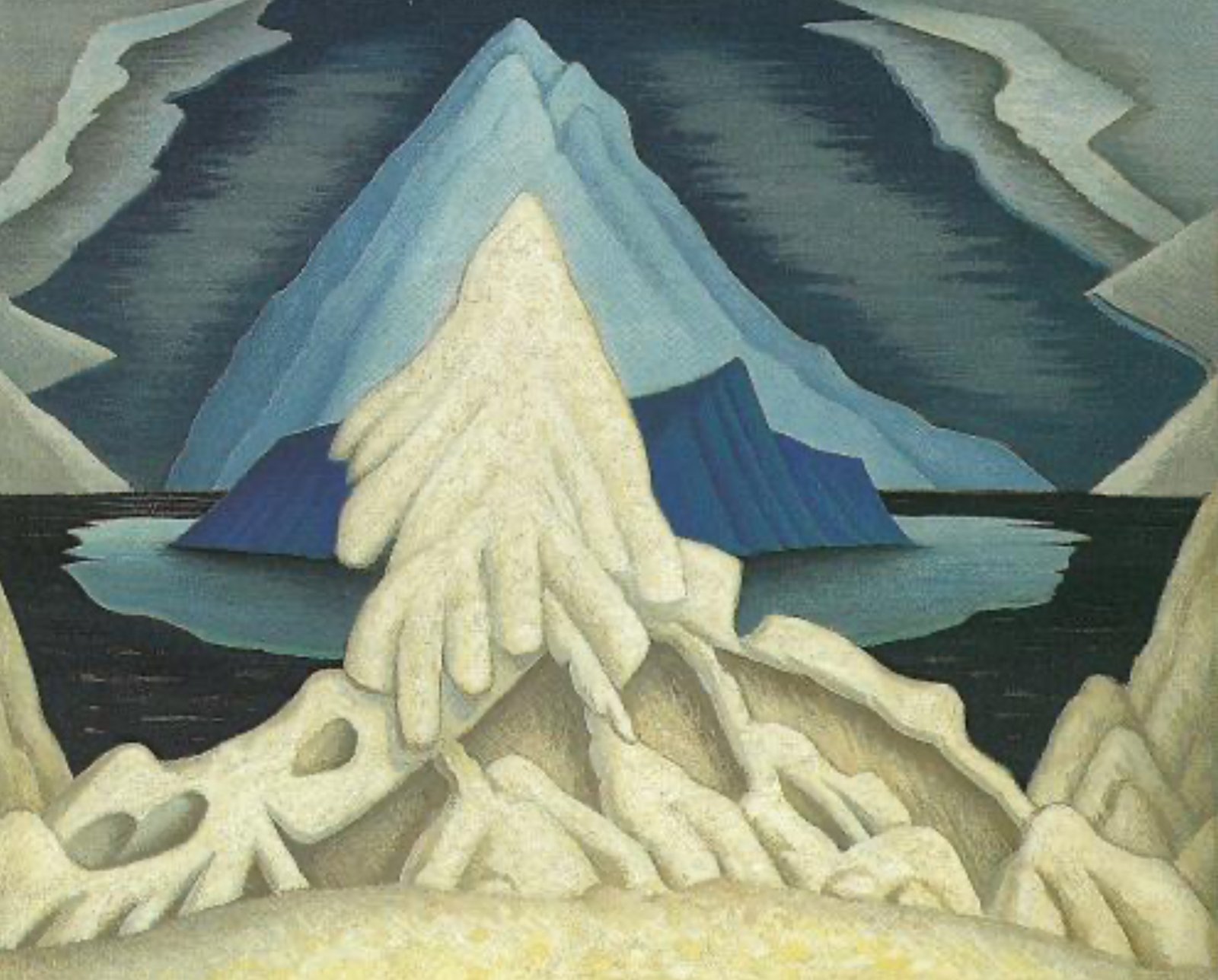

In 1934, shortly after completing some of his most famous paintings, including “Mount Robson” (1929), “Mount Lefroy” (1930), and several Arctic landscapes, Harris went through a significant personal crisis. Some sources suggest he had been in love with Bess Housser, the wife of his friend Frederick Housser, since 1920, when he painted her portrait as “The Christian Scientist.” In 1934, Bess accepted Harris’ offer to move into the apartment where he had his studio. This situation was more than Harris’ wife, Trixie, could endure, leading to the end of their marriage that same year.

The friendship between Harris and Frederick Housser persisted despite these complications. Housser had started a relationship with artist and Theosophist Yvonne McKague (1898–1996) and was waiting for Bess to divorce him so he could marry Yvonne. The only person unhappy with this situation was Trixie Harris, who felt abandoned by Lawren while caring for their three children. In 1934, when Harris quickly obtained a divorce in Nevada and married Bess, Trixie argued that an American divorce was not valid in Canada. She and her influential family claimed that Harris had become a bigamist. As previously mentioned, Harris’ marriage to Bess was abstinent, and they both insisted that true couplehood needed chastity, aligning with a higher Theosophical and artistic ideal. According to Harris, he sought a purer form of art and a purer form of love.

Whether through an abstinent marriage or otherwise, the divorce created quite a scandal in Toronto. In a letter sent to Harris in 1934, Bess described the situation using vintage Christian Science language, despite having joined the Theosophical Society in 1922: “Animal magnetism is known with all its brutal and destructive force directed into one’s own life and vision. It seems to create a great vortex and it will with fiendish delight do away with you there if it can.”

Even after 1934, Harris and Bess occasionally referenced Christian Science while asserting that Theosophy presented a higher form of spirituality. This is evident in their correspondence with Yvonne McKague, the second wife of Frederick Housser, who also felt torn between Christian Science and Theosophy. Harris wrote to her, “Yes, I believe that physical health is an effect of thought, but of right emotion just as much as right thought—and I am not at all convinced that Christian Science has an answer to that… To me the philosophical basis is finer—of Theosophy than it is of C[hristian] S[cience]—much broader and more embracing—it answers my inner questions with a more satisfying sweep and grandeur that thrills something inside me.”

Several Christian Scientists were part of Harris’s circle of friends, including Eric Brown (1877–1939), who supported Harris as director of the National Gallery of Canada, and Doris Huestis Speirs (1894–1989), among others. Speirs was a prominent Canadian ornithologist and the former wife of W. Gordon Mills. Bess maintained regular correspondence with Doris for thirty years.

Harris ultimately decided to leave Toronto and move with Bess to Dartmouth College at the University of New Hampshire in Hanover, where he offered to work for free. During his time in Hanover, Harris deepened his interest in abstract art, a passion that grew after meeting Wassily Kandinsky (1866–1944) and Katherine Dreier (1877–1952). Dreier, both an art patron and an artist, managed the Société Anonyme, and Harris became its only Canadian member. She was crucial in increasing Harris’ international recognition and introduced him to her friend and protégé, Marcel Duchamp (1887–1968). Additionally, Dreier had a close connection to the Theosophical Society.

During this period, Duchamp delved into the concept of a fourth spatial dimension. American art historian Linda Dalrymple Henderson highlights the considerable influence of Theosophy and the works of P.D. Ouspensky on the conceptualization of this spatial fourth dimension. She underlines the pivotal contributions of Theosophist and architect Claude Bragdon (1866–1946), who played a crucial role in articulating a framework for understanding this dimensionality. This notion of a spatial fourth dimension should not be conflated with the temporal fourth dimension that gained prominence following Albert Einstein’s (1879–1955) work.

In Hanover, Harris took the opportunity to explore new artistic ideas, leading him to create his first abstract paintings. His work “Winter Comes from the Arctic to the Temperate Zone” (1935) marks a significant transition from depicting Canadian landscapes to embracing abstract art.

Critics have noted that this evolution may have been influenced by the book “Thought-Forms,” written by Theosophical Society leaders Annie Besant (1847–1933) and Charles Webster Leadbeater (1854–1934).

Massimo Introvigne (born June 14, 1955 in Rome) is an Italian sociologist of religions. He is the founder and managing director of the Center for Studies on New Religions (CESNUR), an international network of scholars who study new religious movements. Introvigne is the author of some 70 books and more than 100 articles in the field of sociology of religion. He was the main author of the Enciclopedia delle religioni in Italia (Encyclopedia of Religions in Italy). He is a member of the editorial board for the Interdisciplinary Journal of Research on Religion and of the executive board of University of California Press’ Nova Religio. From January 5 to December 31, 2011, he has served as the “Representative on combating racism, xenophobia and discrimination, with a special focus on discrimination against Christians and members of other religions” of the Organization for Security and Co-operation in Europe (OSCE). From 2012 to 2015 he served as chairperson of the Observatory of Religious Liberty, instituted by the Italian Ministry of Foreign Affairs in order to monitor problems of religious liberty on a worldwide scale.