While also exploring Christian Science, the greatest modern Canadian painter became an enthusiastic Theosophist.

by Massimo Introvigne

Article 1 of 5 (published on consecutive Saturdays).

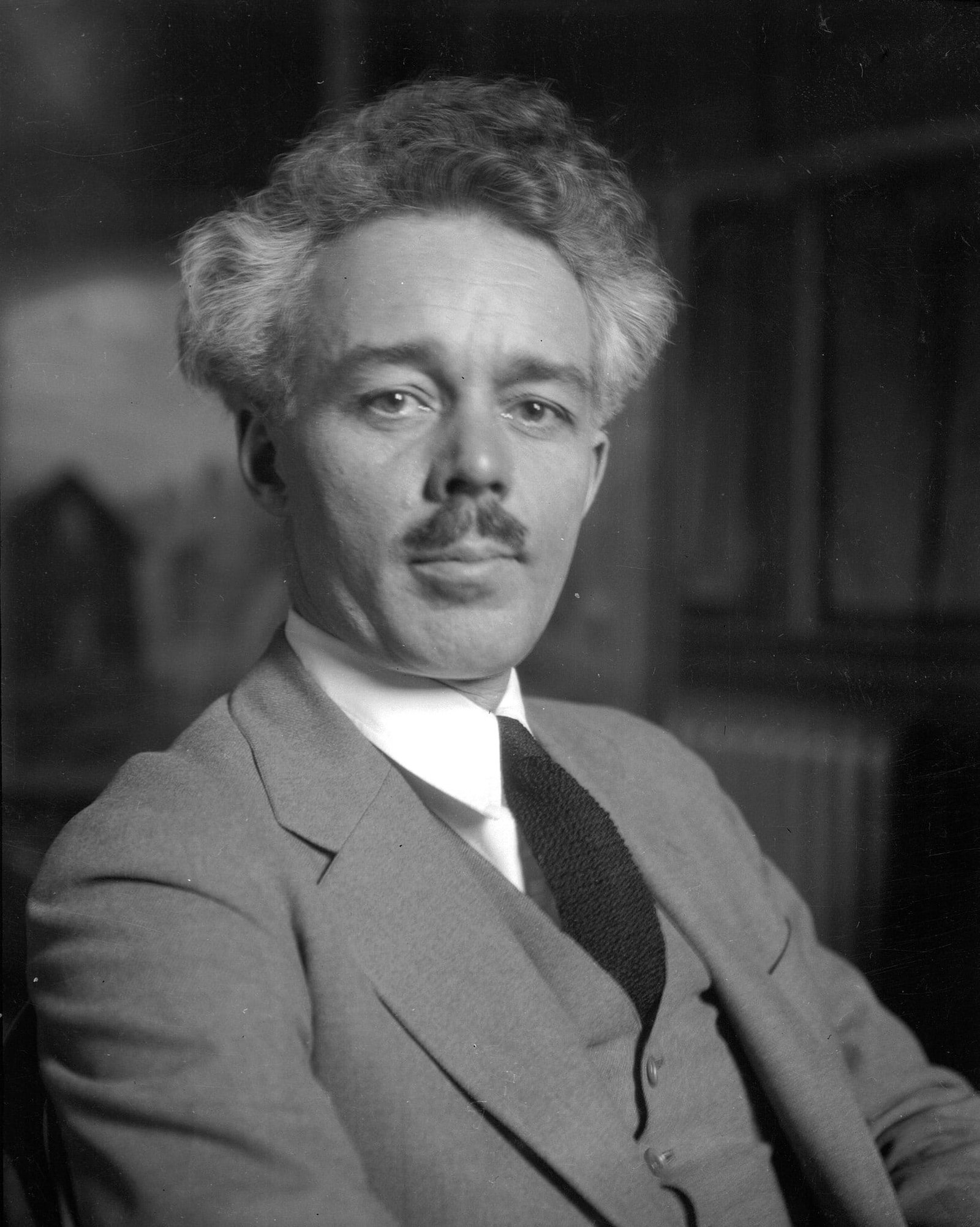

Unlike other Theosophical artists who rarely explored the link between Theosophy and art in-depth, the prominent Canadian painter Lawren Stewart Harris (1885–1970) actively did so. Throughout his career, he produced several articles, manuscripts, and notes on Theosophy.

Many artists in the twentieth century faced poverty. Harris was an exception. Born in Brantford, Ontario, on October 23, 1885, he came from a wealthy family that held significant shares in the Massey-Harris agricultural equipment company. His paternal lineage was Protestant, including several prominent Baptist and Presbyterian ministers. In contrast, his mother was a Christian Scientist, which exposed him to a different religious environment.

In 1884, just a year before Harris’ birth, Toronto journalist Albert Ernest Stafford Smythe (1861–1947) became interested in the Theosophical Society after an unexpected encounter with its American leader, William Quan Judge (1851–1896), while crossing the Atlantic on an ocean liner. Smythe later introduced several Toronto literary elite members to Theosophy, including noted occult enthusiast and novelist Algernon Blackwood (1869–1951). In 1891, Smythe and Blackwood helped establish the Toronto Theosophical Society. As a well-known social figure in Toronto, Smythe enlisted several prominent local literary personalities for this new Society, such as fellow journalist and art critic Frederick Housser (1889–1936) and playwright Roy Mitchell (1884–1944).

Housser, an old friend of Harris from their days as students at St. Andrew’s Presbyterian College, influenced Harris’ decision to seriously pursue Theosophy, which matured after he met Mitchell in 1908. By then, Harris was already established as a painter, thanks to financial support from his affluent family, which enabled him to study the latest European artistic movements in Berlin. He learned from Franz Skarbina (1849–1910), a founder of the Berlin Secession, a group that championed Edvard Munch (1863–1944) against German academic opposition. Skarbina shared his admiration for Munch with Harris and introduced him to prominent Secession artists, including Paul Thiem (1858–1922) and Max Liebermann (1847–1935). Additionally, through Skarbina, Harris encountered the works of Caspar David Friedrich (1774–1840), the Romantic German painter who was a key influence on the Berlin Secession.

Harris, deeply influenced by Thiem and Friedrich, was introduced to what he later called religious “unorthodoxy.” This opportunity allowed the Canadian artist to delve into a spiritual realm beyond Christianity during his travels with journalist Norman Duncan (1871–1916) in the Middle East. Harris created fifty-nine illustrations to accompany Duncan’s articles on his journeys. Upon returning to Toronto, he remained under the sway of his German instructors, focusing on urban landscapes, particularly in very impoverished areas—a pursuit he maintained for several years.

By 1908, he began to emulate Friedrich by venturing North to capture landscapes with snow and towering mountains. He often traveled to Northern Canada with fellow painter Tom Thomson (1877–1917), whom he greatly respected. Tragically, Thomson died in a somewhat mysterious boating accident at Canoe Lake in Ontario’s Nipissing District in 1917. Some critics observed a specific Theosophical influence in Harris’ early landscapes, especially when analyzing what they later termed his cycles of the North.

In the 1910s, Harris was already familiar with Theosophy’s doctrines, although he was initially reluctant to join the Society formally. His skepticism towards organizations played a part in this hesitance, compounded by the fact that his wife, Beatrice (Trixie) Phillips (1886–1962), whom he married in 1910, came from a strict Episcopalian background that viewed Theosophy and similar beliefs as “heresies.” At that time, many of Harris’ closest companions were either members of the Theosophical Society or would become members, including artists James Edward Hervey MacDonald (1873–1932) and Arthur Lismer (1885–1969). MacDonald and Lismer were among the founders of the Group of Seven, which Harris established in 1920 and significantly impacted twentieth-century Canadian art.

The Group of Seven was assembled to foster authentic Canadian art as free as possible from foreign influences. Harris, who was instrumental in selecting its members, also sought to use his means to assist less privileged Canadian artists. Despite its relatively brief existence (disbanding in 1933), the Group greatly impacted twentieth-century Canadian art. The Seven were not only connected by their focus on an independent Canadian art; they also had an interest in alternative spirituality. Three of the original Seven became members of the Theosophical Society, while all shared a basic understanding of and affinity for Theosophical doctrines.

An article by Dennis Reid (1943–2023) from 1968 led several Canadian art historians to recognize the influence of the Theosophical Society on the Group of Seven. However, they often neglected the similar impact of Christian Science, which the artists were exposed to, particularly its fundamental beliefs: that illness does not genuinely exist but is merely a mental error, and that any effort to sway others’ minds embodies a perilous form of “animal magnetism,” which contributes to numerous contemporary ills. Harris’ mother, J.E.H. Macdonald’s wife Joan Lavis (1871–1962), and Frank Hans (Franz) Johnston (1888–1949), one of the Seven, were practitioners of Christian Science. Another Christian Scientist in the proximity of the Seven was Bess Housser (1891–1969), who later became Harris’ cherished second wife and at that time was married to Frederick Housser, a Theosophist and the semi-official publicist and historian for the group. Poet and politician W. Gordon Mills (1886–1960), the closest friend of the Houssers, was also a Christian Scientist.

J.E.H. MacDonald should not be mistaken for James Williamson Galloway “Jock” Macdonald (1897–1969), a later painter influenced by the Group of Seven and by Piotr Demianovitch Ouspensky’s (1878–1945) esoteric ideas. Jock became captivated by Ouspensky’s “A New Model of the Universe,” where the Russian author’s connections to the Theosophical Society are evident. Later, when Harris relocated to Vancouver, he became good friends with Jock Macdonald, noting with delight how the younger artist was intrigued by Eastern religious systems and Theosophical thought.

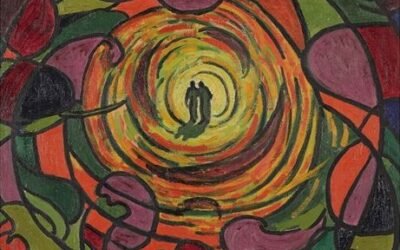

Harris officially became a member of the Theosophical Society in March 1923. However, this does not mean his association with the Society started then. Correspondence shows that several years before 1923, he was already motivating friends to join. In 1922, he was appointed to the Decoration Committee of the Toronto Theosophical Society, serving alongside Mitchell and Lismer. In the years that followed, Harris created his most renowned Canadian landscapes, including famous works like “North Shore, Lake Superior” (1926) and “Isolation Peak” (1929).

His art is characterized by reducing shapes to their essential forms and featuring a stark contrast between light and dark. These elements form part of an aesthetic that Theosophists sought to extract from Madame Helena Blavatsky’s (1831–1891) teachings.

Massimo Introvigne (born June 14, 1955 in Rome) is an Italian sociologist of religions. He is the founder and managing director of the Center for Studies on New Religions (CESNUR), an international network of scholars who study new religious movements. Introvigne is the author of some 70 books and more than 100 articles in the field of sociology of religion. He was the main author of the Enciclopedia delle religioni in Italia (Encyclopedia of Religions in Italy). He is a member of the editorial board for the Interdisciplinary Journal of Research on Religion and of the executive board of University of California Press’ Nova Religio. From January 5 to December 31, 2011, he has served as the “Representative on combating racism, xenophobia and discrimination, with a special focus on discrimination against Christians and members of other religions” of the Organization for Security and Co-operation in Europe (OSCE). From 2012 to 2015 he served as chairperson of the Observatory of Religious Liberty, instituted by the Italian Ministry of Foreign Affairs in order to monitor problems of religious liberty on a worldwide scale.