All of Cornell’s work was but “a variation on the single theme of Christian Science metaphysics,” a statement not by an art historian but by the artist himself.

by Massimo Introvigne

Among the new religious movements that had an important influence on modern art, Christian Science has been less studied than Theosophy. Yet, its role in inspiring artists should not be underestimated. Joseph Cornell (1903–1972) was both the most important Christian Science artist and a crucial figure in the transition from modern to contemporary art.

Cornell came from a well-to-do New York family, but the premature death of his father when he was fourteen left him as the breadwinner for his family, including mother, two younger sisters, and a brother who suffered from cerebral palsy. Joseph himself was tormented by severe stomach pains.

In 1925, he turned to Christian Science, experienced a significant physical healing experience, and became a lifelong active and enthusiastic member of the church. Cornell’s journals make abundantly clear that Christian Science became a primary interest in his life. He credited Christian Science with “the supreme power to meet any human need.”

Cornell turned to art in the 1930s as a way to affirm his faith. In 1951–52, he considered giving up art to devote himself entirely to Christian Science. His collages and “boxes” were his way to organize the world of matter into the purely ideal world advocated by his religion.

Later in life, Cornell stated: “I can’t draw, paint, sculpt, make lithographs.” Self-taught, he was discovered in 1932 by New York gallerist Julien Levy (1906–1981), who introduced him to Salvador Dalí (1904-1989) and other artists and invited him to exhibit with the Surrealists. Cornell produced in 1932 the announcement for Levy’s exhibition “Surréalisme,” and a variation became in 1936 the front cover for Levy’s book “Surrealism.” Mistaken for a Surrealist because of his dreamy boxes, and included in an exhibition of Surrealists at MoMA, the New York Museum of Modern Art, in 1936, he wrote to curator Alfred Barr (1902–1981) that he did not believe he was one, as he was not interested in dreams and the subconscious. For a fervent Christian Scientist, these were dangerously close to the dreaded “animal magnetism.” His boxes and collages were not celebrating chaos but imposing order on it.

However, Cornell wrote to Barr that Surrealism had “healthier possibilities than have been developed.” He probably referred to Marcel Duchamp (1887–1968), whom he admired and befriended. His influence shows in several boxes by Cornell. Cornell agreed with Duchamp’s idea of removing the retinal aspect from art, leaving only the concept, but—as a Christian Scientist—went one step further. He embraced the reality of the object only to prove its ultimate unreality.

Particularly during the celebrations for the hundredth anniversary of his birth (2003), some critics tried to downplay the Christian Science element in Cornell. But in fact, “all [his] work is ultimately a variation on the single theme of Christian Science metaphysics,” a sentence written not by a critic but by Cornell himself. He described the textbook by Christian Science founder Mary Baker Eddy (1821–1910) “Science and Health” as his book “most read of all, exc. Bible.” Separating Cornell’s art from Christian Science is ultimately impossible.

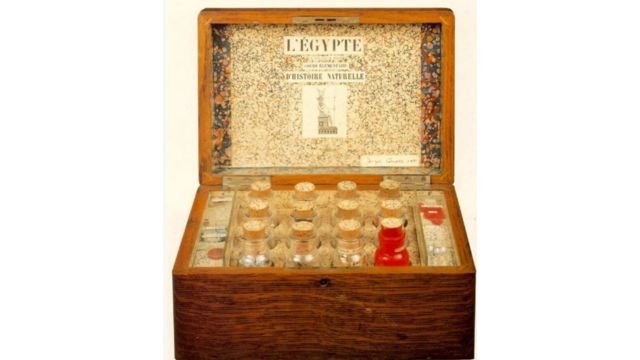

If the absolute was not perceivable by visual perception, it should be looked for beyond the physical confines of traditional art. In addition to boxes, Cornell produced “dossiers” of disparate clippings and objects, and “movies.” These were in fact collages of parts of existing films, starting with “Rose Hobart” (1936), a 19-minute collage film of cuttings from the Universal movie “East of Borneo,” starring Rose Hobart (1906–2000).

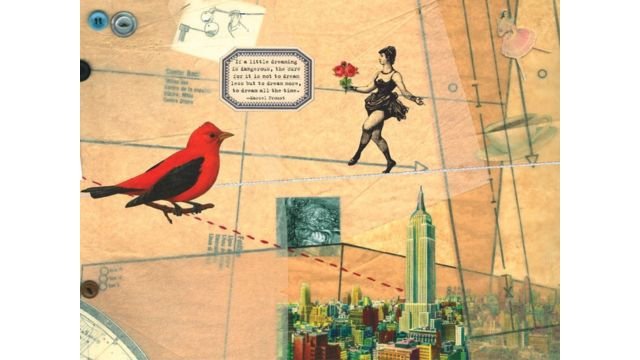

In the assemblage of objects “The Crystal Cage” (1943), Cornell included references to Charles (Émile) Blondin (1824–1897), the French acrobat who crossed more than three hundred times the Niagara Falls on a tightrope. Blondin epitomized for Cornell the Christian Science idea that a trained mind can triumph on physical and material limitations. Blondin was forgotten in the 20th century, but Cornell found a reference to him in Mary Baker Eddy’s “Science and Health”: “Had Blondin believed it impossible to walk the rope over Niagara’s abyss of waters, he could never have done it. His belief that he could do it gave his thought-forces, called muscles, their flexibility and power which the unscientific might attribute to a lubricating oil.”

For the pathologically shy Cornell, the same ability of subduing mental fears was demonstrated by the evolution of ballerinas and actresses before an audience. He devoted several works to movie and ballet stars such as Lauren Bacall (1924–2014), although he also struggled with Eddy’s warning about how easily lust may corrupt admiration for beautiful women and their art. Cornell had a difficult relation with a tyrannical mother. They lived together until she died in 1966, and his invalid brother Robert (1910–1965) also lived in their home. Cornell’s peculiar relationship with this mother explains his problem with women. He had some relationships, including with celebrated Japanese artist Jayoy Kusama (1929–), but they were all short-lived and somewhat platonic, and he reportedly died a virgin.

Ballet, in particular, demonstrated for Cornell the “flexibility and power of the thought-forces called muscles” mentioned by Eddy. He was a great collector of ballet memorabilia. In a small pillbox of 1941 and in other works, he paid homage to Spanish ballerina Rosita Mauri (1850–1923) and to the incident where she reputedly threw her veil at the Russian Czar, disturbed that he was eating caviar with a spoon while admiring her performance.

Later, Cornell became particularly interested in Marilyn Monroe (1926–1962). He started preparing a “dossier” on her when he learned that she had been raised Christian Scientist, first (shortly) by her mother Gladys Baker (1902–1984) and then for five years by her beloved “Aunt Ana,” i.e. Edith Ana E. Lower (1880–1948), a Christian Science practitioner with whom she lived between 1938 and 1942. As a grown-up, Monroe left the faith. She never acknowledged receipt of a box Cornell sent to her. After her tragic death, however, the artist, in his own words, “experienced a totally unexpected revelation,” “a new certainty of Christian Science’s faith in the infinity of divine mind, in death as a pathway to eternal life” and came to believe that Monroe attained in death “an escape from the worldly realm of matter; the triumph of divine spirit.”

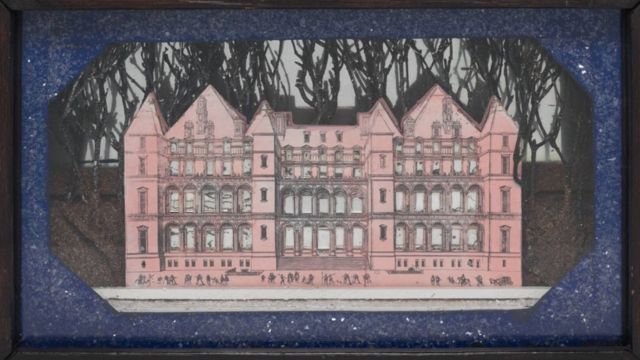

A famous Cornell box, “The Pink Palace” (1946–50) was a reference to the Sleeping Beauty fairy tale (and ballet). The princess awakens after hundred years of sleep, yet she has remained young and beautiful. For Cornell, this related to Christian Science teaching about what Eddy called “the error of thinking that we are growing old, and the benefits of destroying that illusion.” Eddy told the story of a British girl who, “disappointed in love in her early years, […] became insane and lost all account of time. Believing that she was still living in the same hour which parted her from her lover, taking no note of years, she stood daily before the window watching for her lover’s coming. In this mental state, she remained young. Having no consciousness of time, she literally grew no older.” “Years had not made her old, because she had taken no cognizance of passing time nor thought of herself as growing old. The bodily results of her belief that she was young manifested the influence of such a belief. She could not age while believing herself young, for the mental state governed the physical.” This, Eddy believed, was the truth behind the Sleeping Beauty story.

Cornell’s art ultimately aimed at creating “palaces” free of the limitations of the matter and the mortal mind, where the mental state fully governed the physical. Perhaps, this was the true aim of all Christian Science artists, and of Christian Science itself.

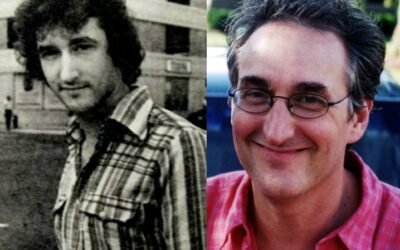

Massimo Introvigne (born June 14, 1955 in Rome) is an Italian sociologist of religions. He is the founder and managing director of the Center for Studies on New Religions (CESNUR), an international network of scholars who study new religious movements. Introvigne is the author of some 70 books and more than 100 articles in the field of sociology of religion. He was the main author of the Enciclopedia delle religioni in Italia (Encyclopedia of Religions in Italy). He is a member of the editorial board for the Interdisciplinary Journal of Research on Religion and of the executive board of University of California Press’ Nova Religio. From January 5 to December 31, 2011, he has served as the “Representative on combating racism, xenophobia and discrimination, with a special focus on discrimination against Christians and members of other religions” of the Organization for Security and Co-operation in Europe (OSCE). From 2012 to 2015 he served as chairperson of the Observatory of Religious Liberty, instituted by the Italian Ministry of Foreign Affairs in order to monitor problems of religious liberty on a worldwide scale.