The rediscovery of a Czech Theosophical artist who decorated an extraordinary esoteric home for a friend and produced iconic woodcuts and paintings.

by Massimo Introvigne

The rediscovery of artists who were involved with Theosophy and a variety of esoteric movements has generated a growing interest for Josef Váchal (1884–1969) as well, in the Czech Republic and beyond. I came across Váchal as part of a broader study of Theosophy, Anthroposophy, and the visual arts in the Czech Republic, and visiting the Portmoneum in 2016 was a memorable and truly unique experience.

Josef Váchal was the illegitimate son of sportsman Josef Aleš-Lyžec (1862–1927), one of the pioneers of modern skiing. His father introduced Váchal to Theosophy, and Josef joined the Theosophical Society at age 19 in 1903. Born in Milavče, in the region of Pilsen, Váchal was raised by his grandparents in Písek. His father, however, decided to support his study of bookbinding in Prague and put him in touch with his cousin, the celebrated academic painter Mikoláš Aleš (1852–1913). Váchal emerged as a talented young artist, although he was more interested in German Expressionism than in Aleš’ academic style.

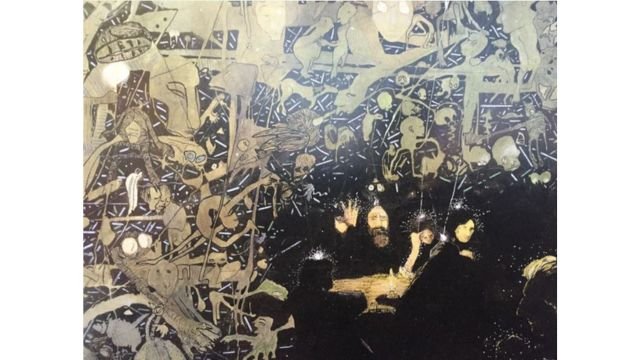

Váchal participated in the gatherings in Prague in the studio of Theosophist and sculptor Ladislav Jan Šaloun (1870–1946), himself an artist with significant esoteric interests and the organizer of Spiritualist séances. Because of his participation in Šaloun’s occult experiments, Váchal started experiencing nocturnal sightings and hearings of beings with misty bodies and feelings of horrible fear. As he later reported, only “when I began to occupy myself with Spiritualism and even with the devil, my fear ceased.” Váchal kept attending Spiritualist séances for years, and the theme never really disappeared from his work.

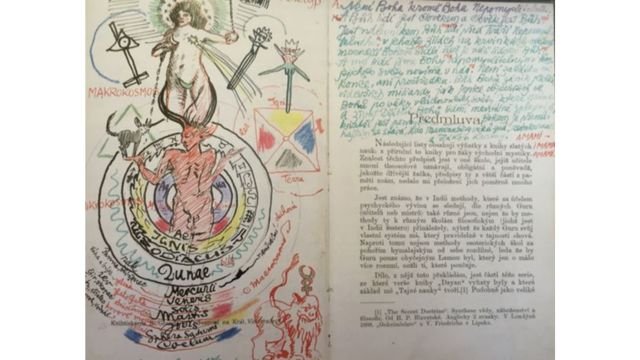

Beyond Spiritualism, the Prague Theosophical Lodge introduced Váchal to a larger tradition of Western and Eastern esotericism. In his 1913 book “Mystics and Visionaries,” he paid homage to the leading figures of Western esotericism, including Jakob Böhme (1575–1624). For seventeen years, from 1903 to 1920, Váchal annotated the Czech edition of Madame Helena Blavatsky’s (1831–1891) book “Foundation of Indian Mysticism” (1898) with comments and fantastic drawings, evidencing his demonological interests. Váchal’s reading of Kabbalah, a recurring theme in his art, was also influenced by Blavatsky.

In 1912, as several other artists did in these years, Váchal produced his own set of divination cards, a variation of the Tarot. Váchal was in touch with the leading exponent of Czech symbolism, František Bilek (1872–1941). Primarily a sculptor (and famous for his “Monument to Comenius,” 1926), Bilek was not a member of the Theosophical Society but was familiar with its literature. Together with Jan Konupek (1883-1950) and others, Váchal founded in Prague in 1910 the Sursum group, devoted to spiritual and occult art and often referred to as the second wave of Czech Symbolism.

Váchal was also influenced by Polish novelist Stanisław Przybyszewski (1868–1927), regarded by Swedish scholar Per Faxneld as the author who “formulated what is likely the first attempt ever to construct a more or less systematic Satanism.” Satanic themes are a constant in Váchal’s work, although serious esoteric allusions often co-exist with the artist’s signature humor.

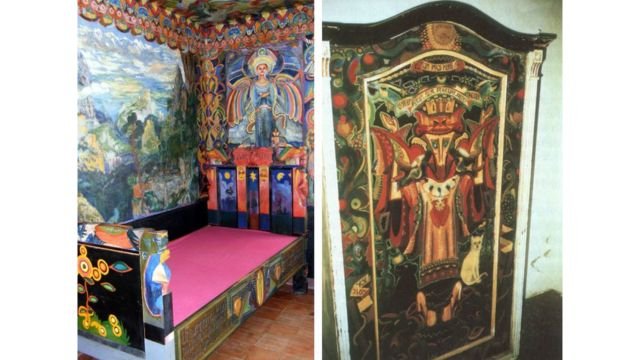

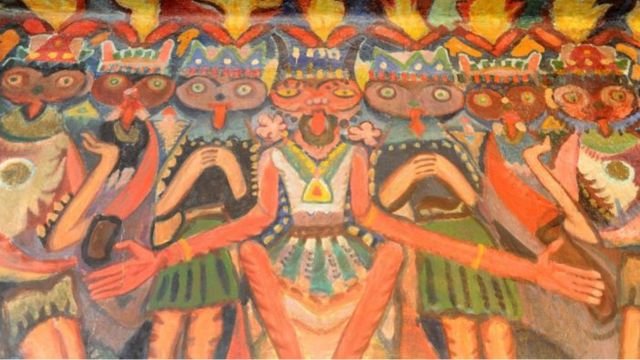

Disturbing satanic, as well as Theosophical and Christian, images were painted by Váchal between 1920 and 1924 in the extraordinary murals in the home of collector Josef Portman (1893–1968), in the Czech city of Litomyšl, where he worked while he was writing his “Blood Novel,” a book including allusions to the home. The Portmoneum is reminiscent of Aleister Crowley’s (1875–1947) Abbey of Thelema in Cefalù, Sicily, but luckily, unlike the Sicilian residence of the British magus, it has been saved from the disrepair into which it felt in Communist times and reopened as a museum in 1993.

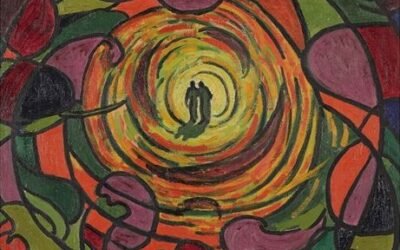

Visiting the Portmoneum, as I did in the Spring of 2016, is like entering a fairy tale, but demons as well as angels lurk in the shadow and there is no guarantee of a happy end. By the time he decorated the Portmoneum, Váchal had become critical of certain secret societies, and one of the murals alludes to the dangers and shortcomings of some of them. Facing the previous mural, another image celebrates the Theosophical unity of all great religions, a pacifying theme overcoming the dangers of the occult.

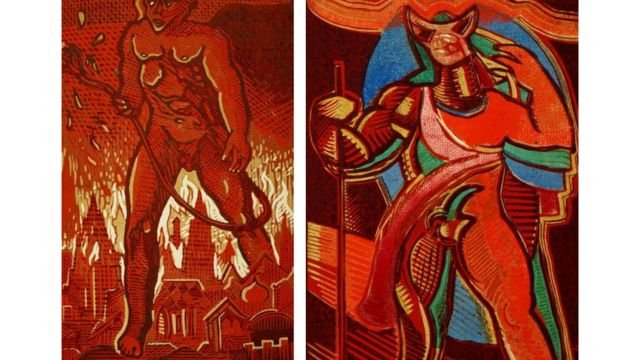

In 1926, Váchal self-published only seventeen copies of a richly illustrated edition of “Hymn to Satan,” by the Italian poet Giosuè Carducci (1835–1907). The poem was in fact a hymn to rationalism, but Váchal interpreted Carducci’s Satan through the lenses of Blavatsky’s comments on Lucifer. The book is currently a collector’s item, commanding high prices in international auctions.

Váchal experimented also with sculpture but was mostly famous for his prints and ex libris woodcuts. During the Communist years, he lived in obscurity and was isolated by the regime, although after the Prague Spring of 1968 he received the medal of “Meritorious Artist” shortly before his death in 1969.

And meritorious, in his own way, he was. Although we can regard some of his artistic experiments as bizarre, he powerfully contributed to the spread of a spiritualist art in what was then Czechoslovakia.

Massimo Introvigne (born June 14, 1955 in Rome) is an Italian sociologist of religions. He is the founder and managing director of the Center for Studies on New Religions (CESNUR), an international network of scholars who study new religious movements. Introvigne is the author of some 70 books and more than 100 articles in the field of sociology of religion. He was the main author of the Enciclopedia delle religioni in Italia (Encyclopedia of Religions in Italy). He is a member of the editorial board for the Interdisciplinary Journal of Research on Religion and of the executive board of University of California Press’ Nova Religio. From January 5 to December 31, 2011, he has served as the “Representative on combating racism, xenophobia and discrimination, with a special focus on discrimination against Christians and members of other religions” of the Organization for Security and Co-operation in Europe (OSCE). From 2012 to 2015 he served as chairperson of the Observatory of Religious Liberty, instituted by the Italian Ministry of Foreign Affairs in order to monitor problems of religious liberty on a worldwide scale.