Before the comics, there were the dime novels of the Belle Époque. Rosicrucians, Theosophists, and occultists were among their most memorable characters.

by Massimo Introvigne

Popular culture emerged, since the late 18th century, as an important vehicle for disseminating novel ideas. Jeffrey Kripal’s “Mutants & Mystics” (2011) showed how comics and TV series popularized esoteric themes and movements. Kripal noticed how modern esoteric organizations became well aware of the role of popular culture, and started placing advertisements in American comics and pulp magazines.

Before comics, however, there were the dime novels. The first were simply novels written as a whole and then cut in chapters sold as weekly instalments. Later, the dime novel adopted the slogan “each instalment a complete story” and, although the main characters remained the same, each 16- or 32-page booklet included a stand-alone illustrated story.

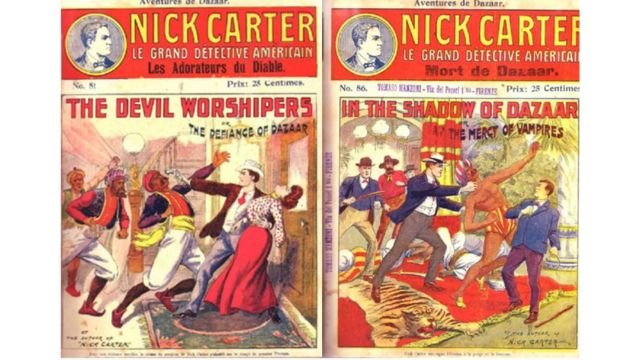

The modern dime novel was created by U.S. publishers Beadle & Adams and Street & Smith. The latter, established in New York in 1855, went on to create a worldwide market through its joint venture with the German company Eichler, which had branches in several countries. The best sold dime novels, featuring the New York detective Nick Carter, reached in 1914, a worldwide weekly readership of 75 million.

After World War I, the dime novel was slowly replaced in the U.S. by pulps (magazines with more than one story) and comics. In Europe, Eichler went bankrupted and its owner committed suicide.

Dead in the U.S., the dime novel continued in Quebec and in Europe throughout the early 1950s, and survived in the Netherlands with one popular character, the gentleman thief Lord Lister, until the 1970s.

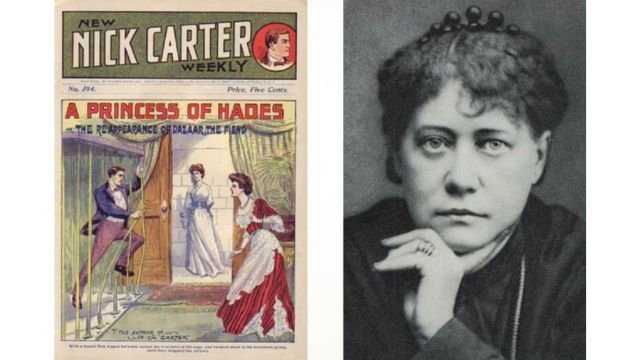

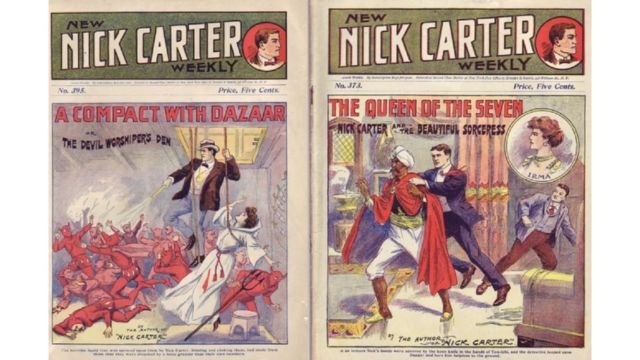

Frederic Van Rensselaer Dey (1861–1922) was not the first, but the main author of the Nick Carter stories. His suicide in 1922 marked the end of the golden era of the dime novels. In 1904, Dey created one of the most intriguing characters of the whole Nick Carter saga, Irma Plavatsky.

While kind and benevolent when she was her normal self, Irma Plavatsky was possessed for long periods by the evil Tibetan magician Dazaar and performed the evilest deeds, which she only vaguely remembered after each episode of possession ended.

The name of Irma Plavatsky obviously evoked Madame Blavatsky (1831–1891), and the New York tabloids had often published lurid exposes of the Theosophical Society. In the early 20th century, many Orientalists regarded Tibetan Buddhism as an inferior form of Buddhism or an entirely different religion, “Lamaism,” dominated by superstition and black magic.

Dazaar was a century-old Tibetan “Master” who created a powerful organization, controlling inter alia all “Satanic lodges” in the world. He was one of the members of the Great White Lodge—another Theosophical concept—who always incarnated in male bodies. Dazaar selected a female body, thus violating White Lodge rules and being sanctioned with expulsion.

Incarnating in a young woman creates in the otherwise omnipotent Tibetan Master a crucial weakness, the potential for human love. As Irma Plavatsky, Dazaar falls in love with Nick Carter. In the end, she has the opportunity of killing the detective, but prefers to shot herself.

Madame Blavatsky was a Russian woman who claimed to be guided by mysterious Oriental Masters. The Dazaar stories also implied that there was something sinister in a spiritual organization led by a white woman controlled by Oriental magicians. As a man, the Tibetan Lamaist-Theosophist Dazaar was perhaps a match for the highly moral Victorian hero Nick Carter. When the Master borrowed a female body, neither Theosophy nor Tibetan Buddhism could seriously compete with Carter’s Christianity and Victorian ethos, and Irma Plavatsky was fatally doomed.

In France, the Eichler group had Dey’s Dazaar cycle not only translated, but somewhat rewritten, by Jean Petithuguenin (1878–1939), an author with some interests in Paris’ esoteric subculture. Influenced by Catholic missionary literature against “Lamaism,” but also by intra-esoteric criticism of Theosophical orientalism, Petithuguenin depicted an even bleaker picture of Plavatsky and the Tibetans, going so far as to call them “Tibetan negroes.”

In the French version, Dazaar borrows from the grave the body of Irma Plavatsky, a deceased fiancée of Nick Carter. In the version by Petithuguenin, Plavatsky does not shot herself, but is magically “called back,” or dissolved, by the Great White Lodge she betrayed. Her last words are also different: “All is lost… All has been in vain… I failed to solve the ultimate enigma.”

In the jargon of the anti-Theosophical Rosicrucianism of Joséphin Péladan (1858–1918) the “ultimate enigma” indicated the “eternal woman” and the mystery of love. It was precisely this enigma that Eastern religions and cultures were regarded as unable to solve, because of their allegedly “inferior” moral code.

The anticlerical Kabbalistic Order of the Rosy Cross and Péladan’s Christian (if unorthodox) Catholic Order of the Rosy Cross, of the Temple and the Grail were both established in Paris in the 1880s. The fight between the two groups amused the tabloids and was nicknamed “the War of the Two Roses.”

Crucial to the amusement were the antics of “Sâr” Péladan, the leader of the Christian group, who was often seen in Paris dressed in the most eccentric garbs. Péladan claimed to have inherited the title “Sâr,” “magician-king,” from remote Babylonian ancestors. Easily dismissed as a charlatan, in fact his “Salons de la Rose-Croix” created a significant international network of artists with esoteric interests. His very notoriety made Rosicrucianism well-known among a general public that would otherwise have ignored it.

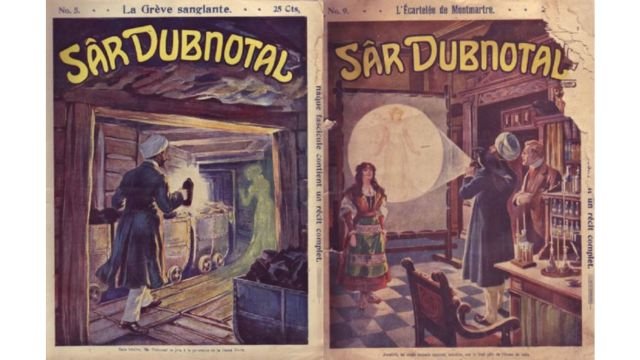

Sâr Péladan became the model for a dime novel character, Sâr Dubnotal, a Rosicrucian who solved several mysteries through Spiritualism and magic. Some claimed that the stories’ author was the respected Norbert Sevestre (1879-1945), but a stylistic analysis shows this as improbable. The series was published by Eichler both in Germany and in France in 1909 and ran for twenty issues only.

Rosicrucians had appeared earlier in popular literature. Gothic horror novels exerted a clear influence on dime novels. In 1811, the very gothic “St. Irvyne; or, the Rosicrucian” was published anonymously in London. His author was none other than the famous poet Percy Bysshe Shelley (1792-1822).

Although technically not a Gothic novel, “Zanoni” (1842) by Sir Edward Bulwer-Lytton (1803–1873) remains the most famous Rosicrucian story in English literature. Belgian painter Jean Delville (1867–1953) conceived the idea of bringing “Zanoni” to a larger audience through the theater or even a movie, but nothing came of it.

Sâr Dubnotal was “the Great Psychagogue” and his author borrowed freely from Theosophy, Spiritualism, and Rosicrucianism. Dubnotal was in telepathic contact with an Indian Master, Ranijesti, but at the same time acquired secret knowledge through Spiritualist séances and “psychognosis,” supposedly a Rosicrucian system of alchemy and ritual magic.

Dubnotal contacts Master Ranijesti and several spirits through the Spiritualist medium Annunciata Gianetti, “brunette, thin, and nervous” and obviously “dressed in Italian fashion,” a fictional character inspired by the real Italian medium Eusapia Palladino (1854–1918).

Just as Péladan claimed he had to do, Dubnotal battled a whole “host of pseudo-psychagogues and fake mediums, whose worthless conjuring tricks so often stop us as we are about to cross the sacred threshold of Mystery.” The worst of these black magicians was the Russian hypnotist Tserpchikopf, later revealed to be Jack the Ripper and killed by Annunciata.

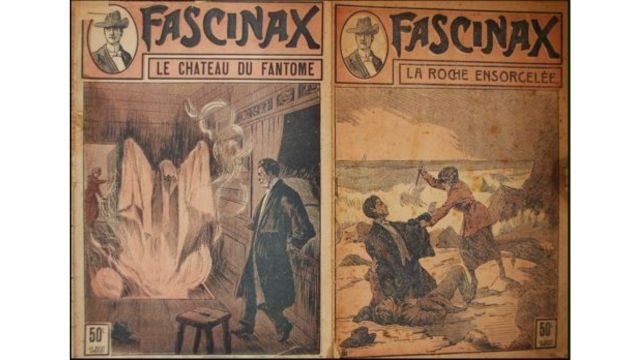

A direct derivation of Sâr Dubnotal (both were schooled by Indian yogis) was a later dime novel hero, Fascinax ,whose stories were possibly authored by the well-known novelist Gustave Le Rouge (1867–1938). The series ran for 22 issues in Paris in 1921 and had two successful Italian translations in 1924 and 1949.

The series started in the Philippines, with the mortal struggle between the benevolent Indian “Buddhist yogi” Nadir Kritchna and the British-born American hypnotist and black magician Numa Pergyll. The latter had Kritchna sentenced to death on false accusations. The yogi was however saved by a British M.D., Dr George Leicester, whom he later initiated into the highest esoteric mysteries and converted into the superhero Fascinax. Pergyll, however, in league with criminals and what the novels called “practitioners of ‘sciences maudites’” of all sorts, continued to fight Fascinax throughout the world.

Fascinax received from an Indian Maharajah as a gift the Stone of Fortune, which confers to his owner mysterious powers. Curiously, the story of Fascinax’s stone was published in Paris shortly before the Russian painter Nicholas Roerich (1874–1947) and his wife Helena (1879–1955), the founders of the Theosophical splinter group Agni Yoga, claimed that the Tibetan Master Morya sent to them, care of a Paris bank, a mysterious package containing a piece of the Stone of Power, Chintamani, a “psychomagnet” transforming its owner and the world through “subtle energies.”

While Rosicrucianism was a Western esoteric tradition, often critic of Theosophy’s Orientalism, dime novels spiced their Western and Rosicrucian superheroes with an Orientalist touch. Both Dubnotal and Fascinax obtained their superpowers from Oriental Masters, and Fascinax identified himself as “a Buddhist.” Another popular dime novel superhero, Ralf Clifford, obtained his power of becoming invisible from the Indian “fakir” Abukabar.

Fascinax lasted longer than Dubnotal and survived until after World War II by incorporating new themes from popular literature and esotericism, including the idea that black magicians were in league with evil extraterrestrials. Fascinax had to fight an invasion from Planet Mars, although in the end it was revealed to be just another delusion created by Pergyll.

While the happy end was mandatory in the dime novels, the villain could be killed off quite cruelly. Pergyll was subjugated by Fascinax and then killed by Raki, the hero’s almost-human dog. “There is an immanent justice—said Fascinax to the dying black magician—and you have the death you deserve: killed by a dog…”

Dime novels occult superheroes such as Dubnotal and Fascinax are different from occult detectives such as Aleister Crowley (1875–1947)’s Simon Iff and Theosophist Algernon Blackwood (1869–1951)’s John Silence, who have a certain knowledge of magic but are not superheroes.

Dime novels are still influential, besides being collectors’ items, with the scarce Dubnotals commanding exorbitant prices. One popular French author influenced by occult dime novels was Jimmy Guieu (1926–2000), whose career included contacts with Rosicrucian and Neo-Templar organizations, including with the controversial Julien Origas (1920–1983). A lecturer on UFO conspiracies, Guieu introduced Rosicrucian superheroes in his widely read “Knights of the Light” series.

In the original 1927 novel “Belphégor” by Arthur Bernède (1871–1937) a presumed ghost was revealed to be a common criminal. In the immensely successful 1965 TV series “Belphégor,” starring Juliette Gréco, the ghost is still a human woman, but she is hypnotized by “the cult of the Rosy Cross.” Finally, in the 2001 movie “Belphegor” starring Sophie Marceau the young woman is possessed by a real spirit.

In “Mutants & Mystics” Kripal argued that the esoteric is marginalized in mainstream culture because of “religious fundamentalism and scientific materialism, which appear oddly united in their ferocious ‘damning’ of the paranormal,” and is mostly disseminated through the alternative popular culture. Things may change, however, perhaps also thanks to scholars like Kripal himself.

Of this I would call, as my final witness, Scooby-Doo. In its (very mainline) stories the “supernatural” monster of the week was always unmasked as an ordinary human villain. However, just as in the evolution of “Bélphegor,” in more recent Scooby stories quite often the ghost or vampire is exactly in the end what it appeared to be in the beginning. Scooby-addicted children are now told that the paranormal exists. Perhaps the esoteric has been finally mainstreamed.

Massimo Introvigne (born June 14, 1955 in Rome) is an Italian sociologist of religions. He is the founder and managing director of the Center for Studies on New Religions (CESNUR), an international network of scholars who study new religious movements. Introvigne is the author of some 70 books and more than 100 articles in the field of sociology of religion. He was the main author of the Enciclopedia delle religioni in Italia (Encyclopedia of Religions in Italy). He is a member of the editorial board for the Interdisciplinary Journal of Research on Religion and of the executive board of University of California Press’ Nova Religio. From January 5 to December 31, 2011, he has served as the “Representative on combating racism, xenophobia and discrimination, with a special focus on discrimination against Christians and members of other religions” of the Organization for Security and Co-operation in Europe (OSCE). From 2012 to 2015 he served as chairperson of the Observatory of Religious Liberty, instituted by the Italian Ministry of Foreign Affairs in order to monitor problems of religious liberty on a worldwide scale.