Her membership in the Theosophical Society is crucial to understand the artist’s themes and idiosyncratic style.

by Massimo Introvigne

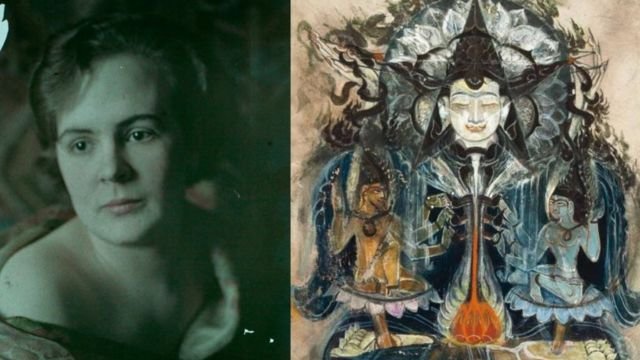

In 2001, an exhibition at the Ateneum Art Museum in Helsinki “rediscovered” the Finnish artist Ilona Harima (1911–1986), whose work is yet another chapter in the long history of the relationships between art and Theosophy.

Ilona Harima, born in 1911 in Vaasa, Finland, was the daughter of Samuli Hohenthal (1879–1962) and Anna Björklund. Samuli, a successful businessman, legally changed his last name into Harima in 1936. The family’s affluence enabled Ilona to pursue art as a career. The family moved to Helsinki in early 1918 due to her father’s work. Ilona attended school there and graduated with a middle-school certificate in 1927. She then briefly studied graphic arts at the Central School of Applied Arts starting in 1928.

She never completed her formal training at the School and abandoned a promising career in advertising to devote herself to the study of esotericism and Eastern religions, and to a very personal style of painting. Ilona joined the Theosophical Society in 1936 and met there her future husband, an architect called Erkki Rautiala, whom she married in 1939.

She became so absorbed by the Theosophical Society’s activities and Eastern religions that she could only explain it with the idea that she had already encountered these doctrines in a previous life.

She also joined the lodge Viisikanta (“Pentagram”: still existing today) of the mixed Freemasonry Le Droit Humain, which had strict connections with Theosophy, and became an active and enthusiastic Freemason.

In 1934, the leading painter and former Theosophist, then Anthroposophist, Hilma af Klint (1962–1944) became aware of Ilona Harima’s activities, praised her work, and wrote to her suggesting that she should study the writings of Rudolf Steiner (1861–1925) and join the Anthroposophical Society. Ilona, however, remained loyal to the spirituality oriented towards the East of the Theosophical Society. She constantly returned to Buddhist and Hindu themes, as evidenced by painting such as “Krishna and Rada” (1953) and “Buddha and Two Bodhisattvas” (1950s).

Although the East was never far away, many paintings by Ilona Harima put together symbols derived from different religious and esoteric traditions, emphasizing the truly Theosophical idea that all religions ultimately converge.

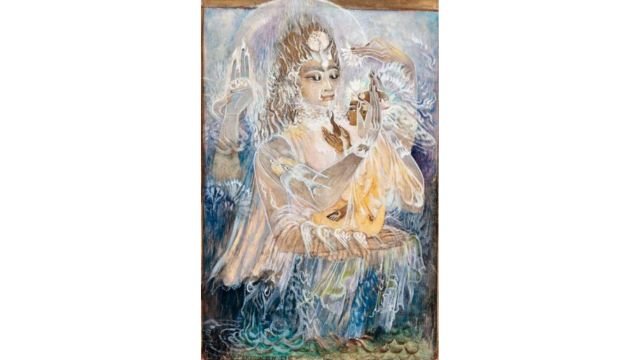

In one of Ilona Harima’s most famous paintings, “Enlightened” (1939), a melancholic girl presents to the Masters a dying bird (the imperfect soul). On the upper right, the bird—the enlightened soul—is alive and well, and ready to fly.

In “Northern Road” (1948) a Master (depicted as Lord Krishna) raises a human soul to awareness, and crowns her with a garland. The enlightened soul deposes its heavier material substance, as she no longer needs it.

Ilona Harima, who was independently wealthy and did not need to sell, rarely exhibited during her lifetime. She died on June 9, 1986. But she was not isolated, her work was praised by art critics, and she felt part of a larger circle of Finnish artists interested in Theosophy and esotericism.

Many of them followed Pekka Ervast (1875-1934), the founder of the Theosophical Society in Finland, who in 1920 seceded from it and founded the independent Rosy Cross Association, in its standard interpretation of the “Kalevala” through Blavatskyan lenses.

Artists in this tradition included Expressionist painter Eemu Myntti (1890–1943) and sculptor Eemil Halonen (1875–1950), followed in a later generation by sculptor Heikki Virolainen (1936–2004).

Massimo Introvigne (born June 14, 1955 in Rome) is an Italian sociologist of religions. He is the founder and managing director of the Center for Studies on New Religions (CESNUR), an international network of scholars who study new religious movements. Introvigne is the author of some 70 books and more than 100 articles in the field of sociology of religion. He was the main author of the Enciclopedia delle religioni in Italia (Encyclopedia of Religions in Italy). He is a member of the editorial board for the Interdisciplinary Journal of Research on Religion and of the executive board of University of California Press’ Nova Religio. From January 5 to December 31, 2011, he has served as the “Representative on combating racism, xenophobia and discrimination, with a special focus on discrimination against Christians and members of other religions” of the Organization for Security and Co-operation in Europe (OSCE). From 2012 to 2015 he served as chairperson of the Observatory of Religious Liberty, instituted by the Italian Ministry of Foreign Affairs in order to monitor problems of religious liberty on a worldwide scale.