The Afghani Hazaras are Shiite, and were repeatedly persecuted by Sunni extremists, leading to four waves of refugees who went to Pakistan.

by Massimo Introvigne

Article 1 of 5

Shiites have been persecuted and targeted by radical Sunni extremists in Pakistan since the 1980s. Although there are Shiites of different ethnicity in the country, one group has paid the heaviest tribute of blood, the Hazaras.

The Hazaras are of Mongolian-Turkic origin, speak a Persian language, and are easily distinguishable for their Mongolian-like facial features. Statistics are in themselves political, but there may be some 700,000 Hazaras in Pakistan, a number that can grow to one million by including refugees from Afghanistan who are not Pakistani citizens.

Hazaras are proud of their Mongolian origins, and like to refer to themselves as descendants of Genghis Khan (ca. 1160–1227). DNA analysis has confirmed that they descend from Mongol soldiers who settled in present-day Afghanistan after the Medieval invasions, but they intermarried with other Turkic and non-Turkic populations. Although there were Hazaras in areas of what its today Pakistan near the Afghan border even before, the Pakistani Hazaras largely derive from comparatively recent migrations from Afghanistan, which started in the 19th century.

Historians have distinguished between four waves of Hazara migration to Pakistan. The first took place in the 1830s and 1840s. It was an economic migration, as Afghan Hazaras were hired by British companies to work in railroad construction and coal mines. Since Hazaras were good warriors, they were also recruited in the British Indian Army, and when service there ended some settled in present-day Pakistan for economic reasons.

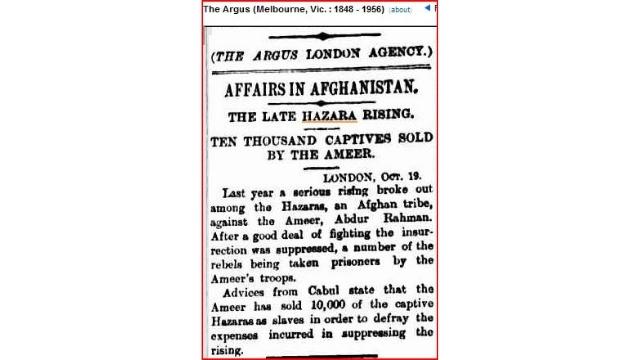

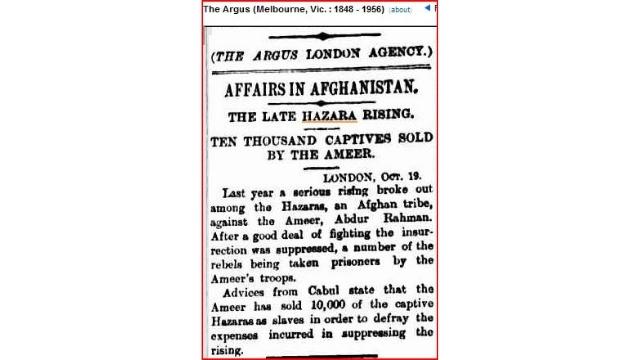

The second migration was of refugees escaping the bloody persecutions of the Amir of Afghanistan Abdul Raman Khan (1844–1901). The Amir is remembered as the father of modern Afghanistan, which he managed to unify and govern with an iron fist. He was also a fanatical Sunni Muslim, who regarded Shi’a as a heresy to be eradicated. In turn, abuses against the Hazara population led to three uprisings against the Amir, in 1888–1890, 1892, and 1893.

Again, statistics are controversial. Historians believe that roughly half of the Hazaras living in Afghanistan were killed, but there was no reliable census of the Afghan population before the 1970s. Reflecting the uncertainty of statistics, estimates of those killed range from 300,000 to 600,000. The numbers fully justify the definition of what happened as a genocide. As in all genocides, there were different motivations for the Amir’s policies, including seizing the properties of well-off Hazaras and a fear that they may side with his relatives who were trying to overthrow him. There was also an old ethnic conflict between the Hazaras and the Pashtuns, the dominant ethnolinguistic group in Afghanistan, which is largely Sunni (although some Shiite Pashtun tribes also exist). However, the religious roots of the genocide, while coexisting with other motivations, cannot be denied.

Britain played an ambiguous role in the Hazara uprisings of the 19th century. British military advisers and some troops helped the Amir. At the same time, the British favored the resettlement of Hazara refugees in British India, while others went to Iran. Of those who remained in Afghanistan and survived the genocide, tens of thousands, particularly women, were sold as slaves. Hazara folklore remembers the story, or legend, of Chehl Dukhtaro, i.e., the “Forty Girls” who committed suicide rather than being captured by the Amir’s soldiers and sold as slaves presumably losing their virginity.

The Hazara community in Pakistan grew with a third wave of refugees, escaping the Communist and Soviet persecution in Afghanistan during the years when the Marxist People’s Democratic Party of Afghanistan (PDPA) was in power, from 1978 to 1992.

Already in 1979, after the arrest of Hazara intellectuals as part of the government’s crackdown on the Muslim elite, the Hazaras demonstrated in Kabul on June 23 and some 2,000 were killed or executed after arrest. At the same time, some Hazaras believed that the Communists would protect them from Sunni persecution, and joined the PDPA. One Hazara, Sultan Ali Keshmand, served twice as Prime Minister during the PDPA years. When the PDPA fell, Keshmand escaped to Russia and then to Britain, where he now advocates for the rights of persecuted Hazaras. Many of the latter never trusted the PDPA, and sought refuge in Pakistan.

The fourth wave of Hazara emigration to Pakistan happened during the civil war and the Taliban era, and continues to this day. The Taliban are part of a Sunni radical movement that regards the Shiite as heretics, and repeatedly carried out massacres of the Hazaras. Hazara sources claim that more than 15,000 have been killed since the fall of the Soviet-backed PDPA regime. Not all have been killed by the Taliban. The so-called Afshar Operation of February 1993 was led by the anti-Taliban Ahmad Shah Massoud (1953–2001) with the aim of eradicating the Shiite militias, including the predominantly Hazara Hezbe Wahdat, which controlled a part of Kabul.

They had fought together with Massoud against the Soviets but now threatened the coalition government. Massoud’s troops entered the Afshar district of Kabul, and the conflict degenerated into a massacre of the Shiite population, both Hazara and non-Hazara. To his credit, Massoud tried to stop the assassination and rape frenzy against the Shiites, but not before hundreds had been killed, and hundreds of women raped.

In August 1998, as a retaliation for the execution of some 3,000 Taliban prisoners in Mazar-i-Sharif (ordered by a Sunni Pashtun commander), the Taliban entered the city and targeted mostly the Hazaras, whom they had declared “non-Muslim” and “infidels.” Estimates of Hazaras killed range from 5,000 to 20,000.

Massacres became routine since the 2010s with the emergence of a new actor, the Islamic State (ISIS), which also regards Shiite as non-Muslim. At least from 2015, ISIS and the Taliban fought each other in Afghanistan. Taliban propaganda occasionally claimed that they were now implementing a politic of toleration of the Hazaras, and massacres were perpetrated by ISIS only. However, as late as 2021, Amnesty International and other NGOs found evidence that the Taliban were slaughtering Hazaras as well. On the other hand, ISIS was responsible of the deadliest incidents, with hundreds of Hazaras strangled, beheaded, or killed by bombs during suicide attacks.

It is not surprising that these incidents led a new wave of Hazara refugees to Pakistan, although some went to the West or to Iran. In Pakistan, these Hazara refugees found the descendants of their co-religionists who had immigrated in the 19th and early 20th century. But they soon discovered they were not safe in Pakistan either.