From his cabin in California, the artist believed he could communicate with deceased, extraterrestrials, and higher beings through a “mental radio.”

by Massimo Introvigne

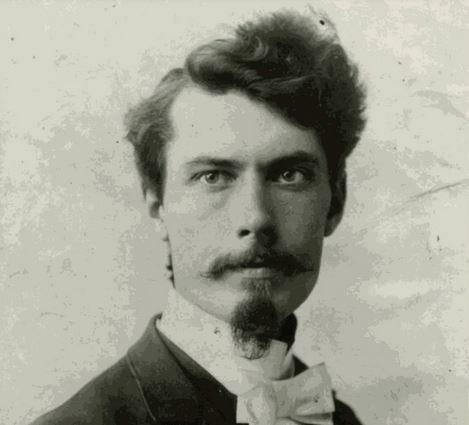

In the quiet hills of Northern California, tucked away in a cabin near Carmel-by-the-Sea, Grant Wallace spent his final decades in communion with spirits, extraterrestrials, and cosmic forces that most of us only glimpse in dreams. A journalist turned mystic, Wallace (1868–1954) was a spiritualist, Theosophist, and self-styled psychic researcher whose art now captivates a new generation of seekers and aesthetes.

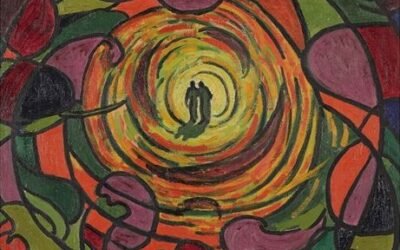

His visionary drawings—exhibited in 2022 at Ricco/Maresca Gallery in New York in the show Over the Psychic Radio and accompanied by a beautiful catalog—are more than artworks. They are transmissions. They are the visual residue of astral conversations, channeled messages, and metaphysical revelations. And they are unlike anything else in American art.

Born in 1868 in Hopkins, Missouri, Wallace’s early life followed a conventional path. He studied at Western Normal College and later at Stanford University, where he developed a passion for languages and literature. He worked as a newspaper editor and war correspondent, covering the Spanish-American War and later serving as a publicist for the Panama-Pacific International Exposition in 1915.

But by the 1920s, Wallace had turned inward—and upward. He became deeply involved in spiritualism, Theosophy, and what he called “psychic” or “mental radio.” He believed that thoughts could be transmitted across space and time, and that specific gifted individuals could tune into these frequencies. Wallace was one of them.

He built a cabin in the woods, surrounded by antennae and experimental devices, and began to receive what he claimed were messages from other planets, dimensions, and lives. He transcribed these messages into elaborate ink and gouache drawings—part diagram, part devotional icon, part cosmic comic strip.

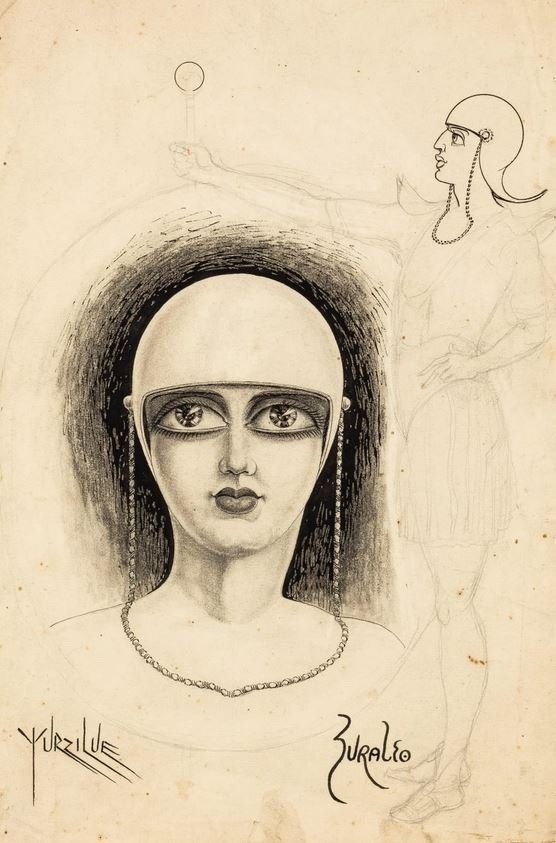

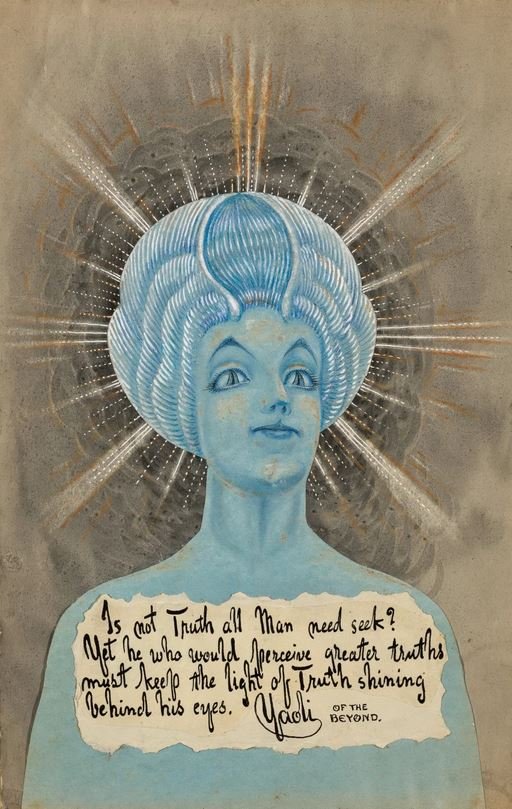

Wallace’s surviving works—thirty-one drawings created between 1919 and 1925—are a kaleidoscope of esoteric symbolism and spiritualist fervor. They feature radiant beings from distant planets, goddesses with flapper hairstyles, and handwritten messages in ornate calligraphy. Many are collaged with torn paper scraps, giving them a raw, urgent energy.

One drawing features a celestial woman named Zuraleo, who is described as an extraterrestrial space traveler. Others show mysterious, radiant figures contacted via the “mental radio.”

These are not idle fantasies. They are spiritual maps. Wallace believed he was documenting real communications from the astral plane, a belief shared by many spiritualists of his era.

Wallace died in 1954, and his work was largely forgotten—until 2021, when his great-grandchildren discovered a trove of drawings and writings in storage. The Ricco/Maresca exhibition, curated with reverence and curiosity, brought his work to light for the first time in decades. The show’s title, Over the Psychic Radio, was taken directly from Wallace’s terminology, a poetic phrase that captured the essence of his practice.

In her essay for the exhibition catalogue, cultural historian Lucy Sante situates Wallace within the broader context of American spiritualism and visionary art. She emphasizes the influence of Theosophy. Wallace’s art and writings clearly reflect Theosophical themes, such as astral travel, cosmic consciousness, and communication with higher beings, and he was familiar with Blavatsky’s writings. No evidence has surfaced, however, that he was a member of the Theosophical Society. Theosophy, for him, was probably more inspiration than affiliation.

But Wallace went beyond Theosophy. Sante notes that Wallace’s “early list of astral contacts includes Egyptians, ancient Greeks, Vikings, Atlanteans; Hippocrates, Thomas Jefferson, Thomas Paine, Charles Dickens, Charles Darwin, and the sociologist Harriet Martineau… Before long, however, he began receiving communications from farther afield, beginning with the other planets of the solar system. He compiled alphabets in Mercurian, Venusian (two social levels), Martian, Jupiterian, Saturnian, Neptunian, and Titanian, pertaining to the largest moon of Uranus. And then he began hearing from entities in the ‘ninth planet,’ Azoth, and eventually from beings on planets of the star Altair, the Pleiades star cluster, and the Andromeda galaxy.”

Today, Wallace’s work feels like a whisper from a deeper source. It invites us to slow down, tune in, and consider the possibility that consciousness is not confined to the brain and that art can be a form of spiritual technology.

For audiences drawn to esoterica, mysticism, and the aesthetics of the unseen, Wallace offers a rare synthesis: the rigor of a journalist, the imagination of a mystic, and the hand of a visionary. His drawings are portals to another world.

And though the Ricco/Maresca exhibition has closed, Wallace’s psychic radio is still broadcasting. All you have to do is listen.

Massimo Introvigne (born June 14, 1955 in Rome) is an Italian sociologist of religions. He is the founder and managing director of the Center for Studies on New Religions (CESNUR), an international network of scholars who study new religious movements. Introvigne is the author of some 70 books and more than 100 articles in the field of sociology of religion. He was the main author of the Enciclopedia delle religioni in Italia (Encyclopedia of Religions in Italy). He is a member of the editorial board for the Interdisciplinary Journal of Research on Religion and of the executive board of University of California Press’ Nova Religio. From January 5 to December 31, 2011, he has served as the “Representative on combating racism, xenophobia and discrimination, with a special focus on discrimination against Christians and members of other religions” of the Organization for Security and Co-operation in Europe (OSCE). From 2012 to 2015 he served as chairperson of the Observatory of Religious Liberty, instituted by the Italian Ministry of Foreign Affairs in order to monitor problems of religious liberty on a worldwide scale.