The Cultural Revolution was a genocidal time in what China calls Inner Mongolia. Today, it’s a cultural genocide.

by Massimo Introvigne

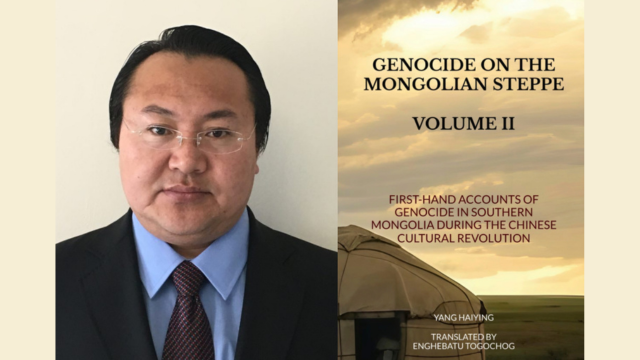

In the vast silence of the Mongolian steppe, history has often been written in whispers—then buried beneath the roar of empire. But with the release of “Genocide on the Mongolian Steppe: First-hand Accounts of Genocide in Southern Mongolia during the Chinese Cultural Revolution (Volume II),” edited by Professor Yan Haiying, translated by Enghebatu Togochog, and published by the Southern Mongolian Human Rights Information Center (SMHRIC), those whispers have become a chorus of remembrance and resistance. China calls “Inner Mongolia” what its local non-Han inhabitants prefer to call “Southern Mongolia.”

This second volume, released in 2025 to mark the centennial of the Inner Mongolian People’s Party, is not merely a continuation of the story—it is a deepening of the wound, and a sharpening of the call for justice. It follows the groundbreaking first volume, published in English in 2017 and based on Yang Haiying’s text, first released in Tokyo in 2009, which exposed the brutal ethnic cleansing campaign launched in 1967 by the Chinese Communist regime. That purge targeted alleged members of the “Southern Mongolian People’s Revolutionary Party,” a phantom organization used as a pretext for mass persecution.

The first volume was a revelation. Drawing on oral histories, interviews, and Yang’s own lived experience, it documented the torture, rape, forced abortions, and executions that left, according to official Chinese sources, nearly 28,000 dead—though independent scholars estimate the toll may be closer to 100,000. Reviewers praised its scholarly rigor and emotional depth, calling it “a rare act of historical recovery.”

Volume II arrives with solemn urgency. It commemorates the 100th anniversary of the Inner Mongolian People’s Party, founded in 1925 as a beacon of national autonomy. That beacon was extinguished in blood during the Cultural Revolution, and this new volume seeks to illuminate the full scope of that darkness.

The book includes newly translated testimonies from survivors, many of whom speak for the first time about the atrocities they endured. These accounts are raw, unfiltered, and often harrowing. One woman recounts being forced to abort her child after being accused of “separatist sympathies.” Another man describes watching his father tortured to death in front of him.

Togochog’s translator’s note frames the book as “a dedication to the hundreds of thousands of Southern Mongolians who lost their lives in the genocide campaign executed by the government of China and Chinese colonial settlers.” But it is also a warning: the genocide continues, albeit in subtler forms.

Today, the battleground is linguistic and cultural. China’s “Second-generation Bilingual Education” policy, introduced in 2020, mandates Mandarin instruction in place of Mongolian in key subjects. This sparked mass protests across Southern Mongolia, with parents, students, and teachers risking arrest to defend their language. The book calls this “cultural genocide”—a term that, while politically charged, captures the existential threat faced by the region’s six million Mongolians.

Volume II documents these contemporary struggles, linking them to the historical trauma of the Cultural Revolution. It argues that the same logic of assimilation and erasure persists, now cloaked in bureaucratic language and educational reform.

What makes this book more than a historical account is its defiance. It insists that Southern Mongolians are not mere footnotes in China’s grand narrative. They are agents of their own history, and their stories—painful, complex, and courageous—deserve to be heard.

While too often geopolitical narratives often drown out indigenous voices, “Genocide on the Mongolian Steppe” is a rare act of reclamation. It challenges readers to confront uncomfortable truths and to recognize that silence, too, can be complicit.

As the centenary of the Inner Mongolian People’s Party reminds us, memory is a tool for survival. And in the windswept steppe, where history was once buried, the voices are rising again.

Massimo Introvigne (born June 14, 1955 in Rome) is an Italian sociologist of religions. He is the founder and managing director of the Center for Studies on New Religions (CESNUR), an international network of scholars who study new religious movements. Introvigne is the author of some 70 books and more than 100 articles in the field of sociology of religion. He was the main author of the Enciclopedia delle religioni in Italia (Encyclopedia of Religions in Italy). He is a member of the editorial board for the Interdisciplinary Journal of Research on Religion and of the executive board of University of California Press’ Nova Religio. From January 5 to December 31, 2011, he has served as the “Representative on combating racism, xenophobia and discrimination, with a special focus on discrimination against Christians and members of other religions” of the Organization for Security and Co-operation in Europe (OSCE). From 2012 to 2015 he served as chairperson of the Observatory of Religious Liberty, instituted by the Italian Ministry of Foreign Affairs in order to monitor problems of religious liberty on a worldwide scale.