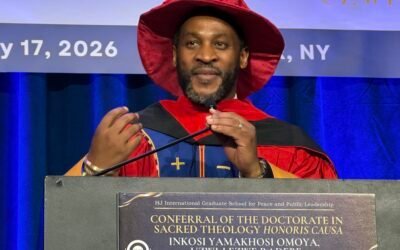

The church will celebrate its centenary in 2026. Its origins explain its success.

by Massimo Introvigne*

*A paper presented at the CESNUR 2025 conference, Cape Town, South Africa, November 18, 2025.

My theme today is not to delve into present controversies about La Luz del Mundo, the second-largest religion in Mexico, but to reflect on its origins in light of the forthcoming centenary celebrations in 2026.

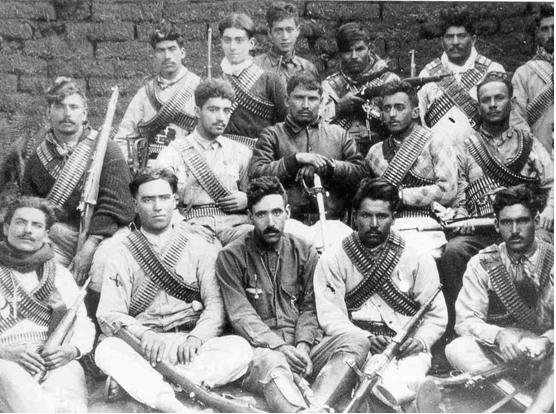

Let us rewind to December 12, 1926. Guadalajara was ablaze with devotion and contradiction. The feast of Our Lady of Guadalupe filled churches with prayer and streets with revelry—dancing, drinking, and even brothel visits. But beneath the incense and tequila, tension simmered. The Cristero War was about to explode. President Plutarco Elías Calles, Mexico’s secularist-in-chief, had declared war on the Catholic Church. Just months earlier, 400 Catholics had occupied a church and exchanged gunfire with federal troops. Eighteen died. The city braced for rebellion.

Into this combustible mix walked a ragged preacher from Monterrey, accompanied by his wife, Elisa. His name was Eusebio Joaquín González, though he had recently adopted the biblical name Aarón. Few noticed him. Fewer still suspected that this quiet man carried the seed of what would become Mexico’s second-largest religious organization.

To understand Aarón’s journey, we must first revisit the Cristero War’s historiography. For decades, it was cast as a peasant revolt against a revolution that failed to deliver justice. Jean Meyer, the French-Mexican historian, famously reframed it as a religious war—coining the term “Cristiada,” which later inspired a Hollywood movie on the conflict. His revisionism, though well-documented, was criticized for romanticizing the Cristeros. Then came Matthew Butler, who argued that both Meyer and the dominant narrative missed the mark. The war wasn’t a binary clash of saints and sinners. Cristeros included wealthy landowners; Calles’ supporters included devout believers. Religion was central, yes—but never alone. Wars are messy. So are revolutions. And so, it turns out, are religious awakenings.

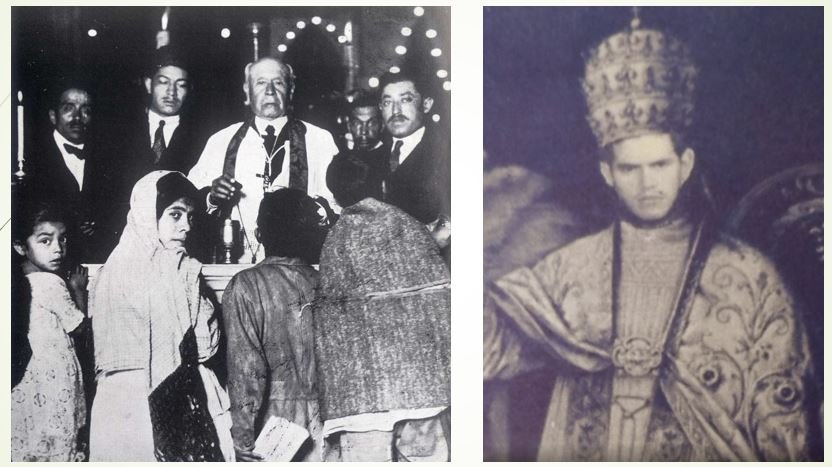

While Catholics and secularists clashed, Protestantism in Mexico remained a minority affair. Despite its 19th-century roots, Protestants never cracked the Catholic monopoly. Catholic propaganda painted them as imports—American, schismatic, and un-Mexican. “All Mexicans are Guadalupanos,” Catholics joked, much to the annoyance of non-Catholics. The Virgin of Guadalupe allegedly appeared to Juan Diego in 1531 and was the ultimate symbol of Mexicanness. Even President Calles, the secularist, understood this. He tried to create a government-friendly schismatic church—the Iglesia Católica Apostólica Mexicana (ICAM). It flopped. Mexicans preferred the original.

But what if the divine had already appeared to a non-Catholic in Mexico? Aarón believed it had—on April 6, 1926.

Born in Colotlán, Jalisco, in 1896, Eusebio Joaquín González was moreno—dark-skinned—like most Mexicans. His family fled uprisings and settled in Tlaltenango, Zacatecas, where Eusebio became a teacher. Inspired by revolutionary ideals, he joined Pancho Villa’s militias, only to be disillusioned by their brutality. He switched sides, joining Carranza’s constitutionalists. Military life, however, left him spiritually unsatisfied.

In 1925, Eusebio married Elisa Flores. While stationed in Coahuila, Elisa met Rosa Murillo, a Pentecostal merchant linked to Romanita Carbajal de Valenzuela, a Mexican woman who had attended the 1906 Azusa Street revival in Los Angeles—the birthplace of global Pentecostalism. Rosa introduced Elisa to the Iglesia Evangélica Cristiana Espiritual (I.E.C.E.), part of the Oneness Pentecostal tradition, which rejected the Trinity and baptized in Jesus’ name only.

Through Elisa, Eusebio met Francisco Borrego Martínez, leader of the I.E.C.E., and two eccentric prophets: Antonio Muñoz (Saulo) and Francisco Flores (Silas). These men looked like biblical throwbacks with sandals, tunics, and flowing beards. They claimed prophetic visions and opposed institutional pastors, stirring chaos across Mexico’s Pentecostal networks.

Silas baptized Eusebio in late 1925. His newfound faith clashed with military duty—especially when ordered to execute a man. He refused, citing Scripture, and left the army. He and Elisa followed Saulo and Silas to Monterrey, only to discover that the prophets’ moral compass was, so to speak, creatively calibrated. They treated the couple as unpaid servants.

Then came the night of April 6, 1926. Eusebio, asleep, was jolted awake by a thunderous voice. First, the voice proclaimed: “Here is a man whose name will be Aarón.” Second, a large white hand singled him with an index finger, and the same voice added: “Your name shall be Aarón.” Third, he saw stars in the firmament that spelled the phrase and heard the voice proclaim, “Your name shall be Aarón, I will make this name known around all the world, and it will be a blessing.” Unlike his prophetic mentors, Aarón didn’t claim mere inspiration. He believed God had restored the primitive Christian Church and appointed him as its Apostle. This elección, or apostolic calling, became the cornerstone of La Luz del Mundo’s theology.

Commanded to leave ”next Thursday,” Aarón set out on foot for Guadalajara with Elisa and a few followers. The journey was perilous—bandits, rebels, and rejection awaited. His Catholic family disowned him. But Aarón persisted, working odd jobs to support his growing community and family. His first son, Pablo, was born in 1928. Seven more children followed.

Early meetings were held in homes. In 1934, the group acquired a modest worship space in Sector Libertad, Calle 46. Aarón claimed God revealed the church’s name: “Iglesia del Dios Vivo Columna y Apoyo de la Verdad La Luz del Mundo” (Church of the Living God, Pillar and Ground of the Truth, The Light of the World). Legal documents used simpler names, but the divine branding stuck.

By then, Aarón had ordained male ministers and two female deaconesses, one of whom was Elisa. In 1931, he presided over the first Santa Cena (Holy Supper), later fixed on August 14, his birthday. This annual event would evolve into a spectacular international ceremony.

With the Cristero War over, Aarón expanded beyond Jalisco, planting congregations across Mexico. In 1938, construction began on a larger temple in Calle 12 de Octubre, Reforma. That same year, Aarón requested rebaptism—this time in Jesus’ name only—correcting the Trinitarian formula used by Silas.

By the early 1940s, La Luz del Mundo boasted 130 congregations and 2,000 members. Many early converts came from Oneness Pentecostalism, bringing a penchant for schism. Small breakaways occurred in 1932 and 1936, but the largest came in 1942, led by José María González, Aarón’s first ordained pastor.

Despite internal conflicts, the church grew because it offered something many Mexicans sought. They had welcomed the Mexican Revolution and were critical of the Catholic Church’s involvement with the old, reactionary order. However, they were not atheists and did not support the secularist or Marxist ideas of some revolutionary leaders. They were wary of Protestant churches from abroad, especially the United States. La Luz del Mundo was critical of Catholicism, deeply spiritual, and proudly Mexican.

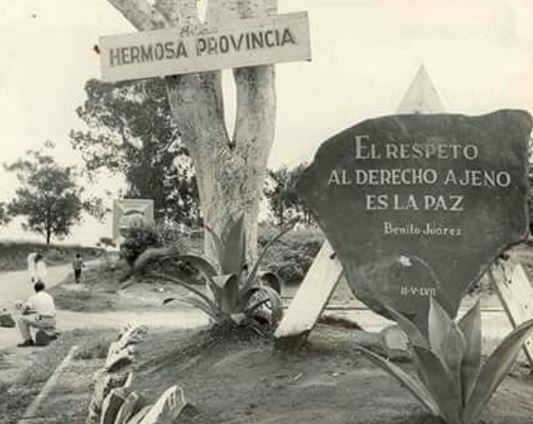

Members began settling near the temple, but faced hostility from Catholic neighbors. Aarón seized an opportunity: Guadalajara’s City Council promoted “fraccionamientos”—planned neighborhoods. In 1954, he bought land east of the city center. Thus was born Hermosa Provincia (Beautiful Province), a “colony for the children of God.”

In 1957, municipal authorities dedicated a monument to Benito Juárez at Hermosa Provincia’s entrance, marking the centennial of his liberal Constitution. The colony became a model—Mexico’s first to eradicate illiteracy—and the church became global.

Aarón died on June 9, 1964, leaving behind 20,000 members and congregations across Mexico and abroad. Under his successors, La Luz del Mundo grew to millions. But that would be a story for another session.

Today, as we approach the centennial of La Luz del Mundo, we remember not just a church, but a journey—from thunderclaps in a Monterrey bedroom to temples and colonies that reshaped Mexican religious life. Aarón’s story is one of vision, resilience, and reinvention. And whether one sees divine providence or historical coincidence, the name Aarón did, indeed, become known around the world—and it remains, if controversial for some, a blessing to many.

Massimo Introvigne (born June 14, 1955 in Rome) is an Italian sociologist of religions. He is the founder and managing director of the Center for Studies on New Religions (CESNUR), an international network of scholars who study new religious movements. Introvigne is the author of some 70 books and more than 100 articles in the field of sociology of religion. He was the main author of the Enciclopedia delle religioni in Italia (Encyclopedia of Religions in Italy). He is a member of the editorial board for the Interdisciplinary Journal of Research on Religion and of the executive board of University of California Press’ Nova Religio. From January 5 to December 31, 2011, he has served as the “Representative on combating racism, xenophobia and discrimination, with a special focus on discrimination against Christians and members of other religions” of the Organization for Security and Co-operation in Europe (OSCE). From 2012 to 2015 he served as chairperson of the Observatory of Religious Liberty, instituted by the Italian Ministry of Foreign Affairs in order to monitor problems of religious liberty on a worldwide scale.