Comments emphasized China’s and Pakistan’s ability to maneuver smaller countries. The question, however, is ethical before being political.

by Massimo Introvigne

There have been many comments on Pakistan’s victory at UNESCO on November 24, where it was elected as Vice-Chair of the organization for the term 2023–2025, representing the Asia-Pacific Group. Pakistan defeated India in the election, and some comments criticized the limited effectiveness of the current Indian representative to the UNESCO. Others emphasized the role of China, which is especially skilled in mobilizing developing countries and defeat the West and its allies in elections at the United Nations bodies.

Few, however, commented on the inherent paradox of having Pakistan in a top position at the UNESCO. The organization has among its stated aims promoting freedom of expression, safety of the journalists, and equal respect for all cultures, and protecting historical monuments. Pakistan has an abysmally low record in these fields (not that China, its main sponsor in the UNESCO election, has a better one). It was like electing the proverbial fox to guard the equally proverbial henhouse.

Pakistan has one of the worst laws (in fact, a complex of laws) in the world preventing freedom of expression, its notorious anti-blasphemy statute. Even vague criticism of Islam, or a false accusation of it, count as blasphemy, which is punished by the death penalty. The bad Pakistani law on blasphemy has recently been amended—to make it even worse.

According to the Committee to Protect Journalists, 97 journalists and media workers were killed in Pakistan between 1992 and 2023, not to mention the Pakistani reporters killed abroad such as Arshad Sharif. He was kidnapped, tortured, and shot in Kenya in October 2022, with Pakistan’s intelligence strongly suspected of the homicide. Earlier this year, Audrey Azoulay, Director-General of UNESCO, condemned the killing of yet another journalist, Jan Mohammad Mahar, in the city of Sukkur in Pakistan, on August 13.

Cultures different from Sunni Islam are heavily discriminated in Pakistan. Ahmadis are officially considered second-class citizens and Hazara Shiites are targeted by mob violence and terrorist attacks. Hindus, Sikhs, and Christians see girls in their communities kidnapped, raped, and forcibly converted to Islam and married to Muslims—a plague denounced by the United Nations themselves. Afghan refugees are deported back to Afghanistan in what increasingly looks like a genocide.

Christian churches are burned by mobs. Historical Hindu temples are destroyed, converted into cattle farms, or repurposed as Islamic places of worship.

Yes, it is the fox called to guard the henhouse. And China is placing as many foxes as possible in similar positions in United Nations agencies. One day, the foxes will open the door of the henhouses to Beijing’s Big Bad Wolf.

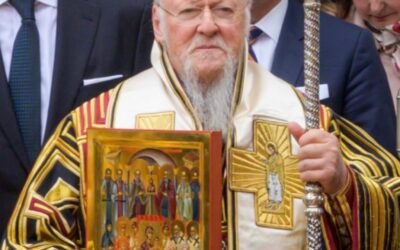

Massimo Introvigne (born June 14, 1955 in Rome) is an Italian sociologist of religions. He is the founder and managing director of the Center for Studies on New Religions (CESNUR), an international network of scholars who study new religious movements. Introvigne is the author of some 70 books and more than 100 articles in the field of sociology of religion. He was the main author of the Enciclopedia delle religioni in Italia (Encyclopedia of Religions in Italy). He is a member of the editorial board for the Interdisciplinary Journal of Research on Religion and of the executive board of University of California Press’ Nova Religio. From January 5 to December 31, 2011, he has served as the “Representative on combating racism, xenophobia and discrimination, with a special focus on discrimination against Christians and members of other religions” of the Organization for Security and Co-operation in Europe (OSCE). From 2012 to 2015 he served as chairperson of the Observatory of Religious Liberty, instituted by the Italian Ministry of Foreign Affairs in order to monitor problems of religious liberty on a worldwide scale.