The unique status of religious freedom among human rights implies that religions should be able to self-organize and be granted tax exemptions.

by Setsu Kobayashi

Article 2 of 5. Read article 1. Note: We have kept the parenthetical references of the Japanese original.

Religious freedom as a superior human right and strict standard for constitutional scrutiny

As mentioned in the first article, even if one asserts religious freedom, crimes committed in the name of religion (such as bigamy) are not permitted. However, the U.S. Supreme Court has treated religious freedom as a “superior human right” in the human rights system when it is a sincere religious claim.

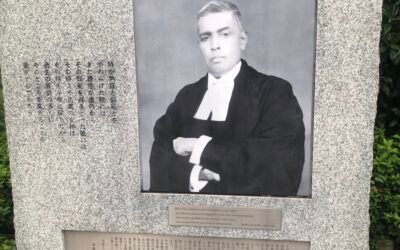

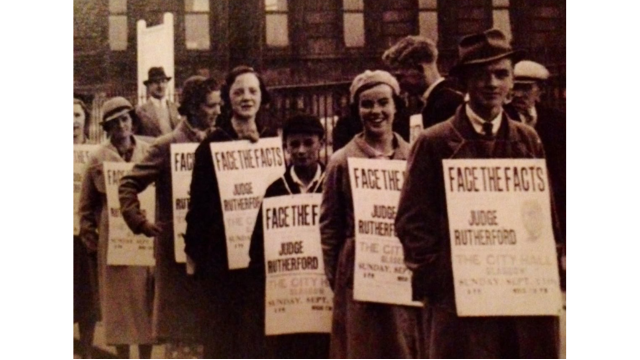

For example, in a 1943 Supreme Court decision on the “West Virginia State Board of Education” case, which challenged the constitutionality of forcing Jehovah’s Witnesses to swear an oath of loyalty to the state, the Court ruled that freedom of worship may not be infringed on such slender grounds as “rational basis.” “They [religious liberty rights] are susceptible of restriction only to prevent grave and immediate danger to interests which the State may lawfully protect” (“West Virginia State Board of Education v. Barnette,” 319 U.S. 624 [1943], at 639).

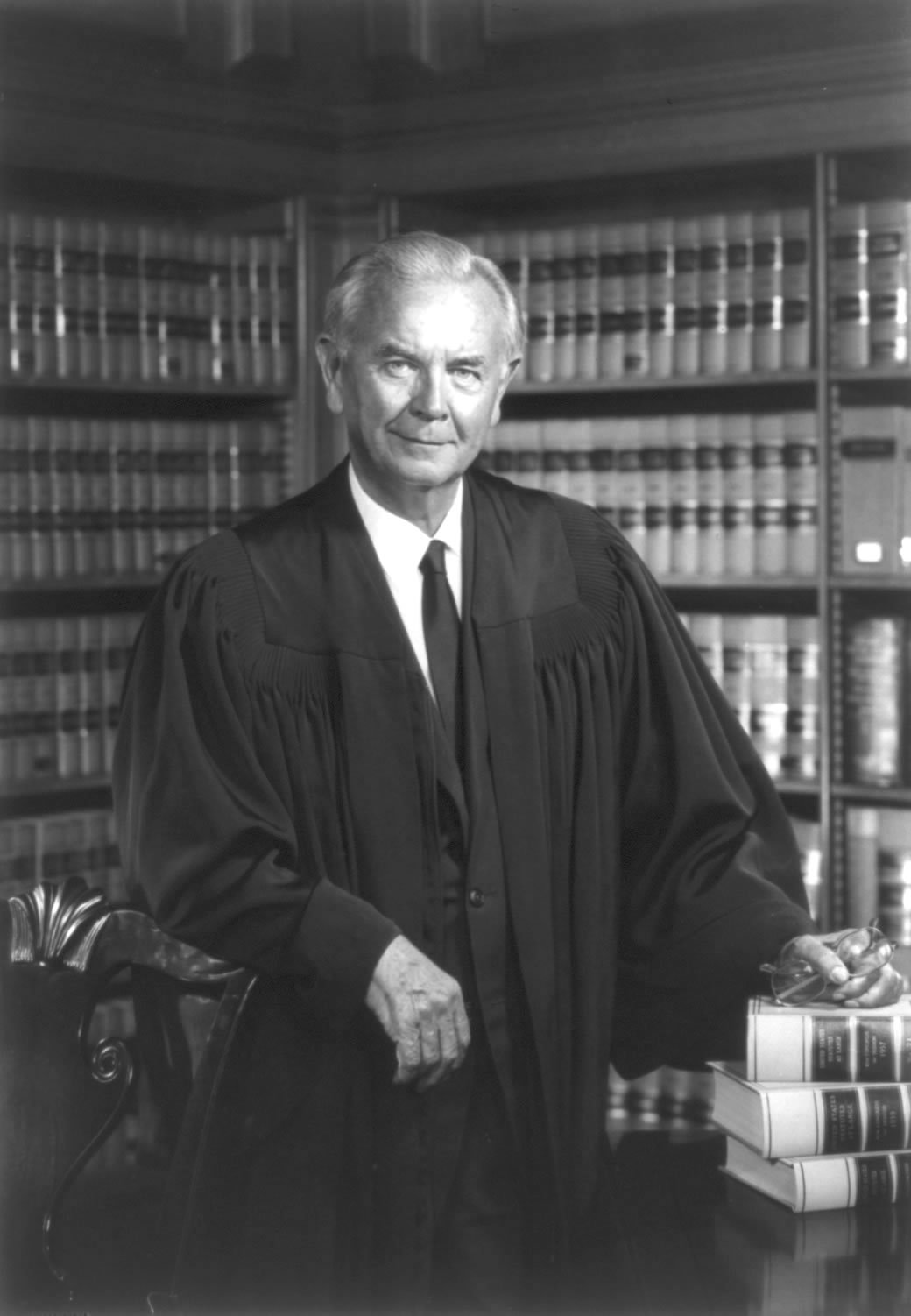

Since then, the US Supreme Court has consistently followed this position: “Only the gravest abuses, endangering paramount interests, give occasion for permissible limitation” (“Sherbert v. Verner,” 374 U.S. 398 [1963]). “The state may justify an inroad on religious liberty by showing that it is the least restrictive means of achieving some compelling state interest” (“Thomas v. Review Board of the Indiana Employment Security Division,” 450 U.S. 707 [1981]). “Only those interests of the highest order and those not otherwise served can overbalance legitimate claims to the free exercise of religion” (“Wisconsin v. Yoder,” 406 U.S. 205 [1972]). “Even though the governmental purpose be legitimate and substantial, that purpose cannot be pursued by means that broadly stifle fundamental personal liberties when the end can be more narrowly achieved. The breadth of legislative abridgment must be viewed in the light of less drastic means for achieving the same basic purpose” (“Wooley v. Maynard,” 430 U.S. 705 [1977]).

“[The state] must show that its regulation is necessary to serve a compelling state interest, and that it is narrowly drawn to achieve that end” (“Widmar v. Vincent,” 454 U.S. 263 [1981]). “When a state denies receipt of a benefit because of conduct mandated by religious belief… that denial must be subjected to strict scrutiny, and can be justified only by proof of a compelling state interest” (“Hobbie v. Unemployment Appeals Commission of Florida and Lawton & Company,” 55 U.S. L.W. 4206 [1987]), etc.

The importance of “association” in religious activities

When people seek to enjoy religious freedom, it is extremely natural and effective for people of the same faith to come together to form groups and practice their faith. In a free society, all religions are minorities and “strange” when viewed from the perspective of society as a whole. Therefore, the “freedom of religious association” that allows like-minded people to gather together has been guaranteed as an essential aspect of religious freedom. Thus, an order by the state to dissolve a religious group is a vitally serious disadvantage for believers, as it means they lose the central foundation of their faith.

The significance of tax exemptions for religious corporations

If a religious corporation is certified, it will be given tax-exempt treatment, just like other public interest corporations (schools, hospitals, charitable organizations, etc.).

This is often seen as a “financial advantage” (privilege), and some argue it is unjust reverse discrimination. However, the essential function of the tax exemption is not financial advantage, but “non-interference of political power with religion.”

In “Walz v. Tax Commission of the City of New York,” 397 U.S. 664 (1970), in which the constitutionality of the property tax exemption for religious corporations was established, the Supreme Court stated the following: “Grants of exemption historically reflect the concern of authors of constitutions and statutes as to the latent dangers inherent in the imposition of property taxes; exemption constitutes a reasonable and balanced attempt to guard against those dangers. We find it unnecessary to justify the tax exemption on the social welfare services or ‘good works’ that some churches perform for parishioners and others… To give emphasis to so variable an aspect of the work of religious bodies would introduce an element of governmental evaluation and standards as to the worth of particular social welfare programs, thus producing a kind of continuing day-to-day relationship which the policy of neutrality seeks to minimize. Hence, the use of a social welfare yardstick as a significant element to qualify for tax exemption could conceivably give rise to confrontations that could escalate to constitutional dimensions. [A]n unbroken practice of according the exemption to churches… is not something to be lightly cast aside… [It] has helped to guarantee the free exercise of all forms of religious belief…”

In light of this principle, the cancellation of the certification of a religious corporation (dissolution order) should not be taken lightly. In other words, it is often said that it is not a problem or that it is a minor issue because “even if a corporation loses its legal status, its followers can continue their religious activities as a voluntary organization…” (Kazuhiro Mitsunobu, “42 Religious Corporation Dissolution Orders and Freedom of Religion,” “Constitutional Case Law 100 Selected I” [5th Edition], p. 87).

However, if a corporation is dissolved, the new group as a voluntary organization will be placed under the supervision of the tax authorities. For religious people, this is tantamount to a significant restriction being imposed on their faith itself. For any person or organization, you can find out everything they do by looking at the money flow. Therefore, for a religious organization, having its accounting subject to supervision by public authorities is tantamount to having its faith itself controlled. Moreover, since this is a restriction imposed on a “superior human right,” it is not acceptable for it to be imposed without a significant public interest purpose and fair procedures.

Setsu Kobayashi is a professor emeritus at Keio University and a lawyer. He is a Doctor of Law and a Honorary Doctor of Otgontenger University, in Ulaanbaatar, Mongolia. Born in Tokyo in 1949, he completed his doctoral course at Keio University Graduate School of Law in 1977. After working as a visiting scholar at Harvard Law School, he was a professor at Keio University from 1989 to 2014. During that time, he also served as an invited professor at Peking University and an associate fellow at Harvard University’s Kennedy School of Government. In 2014, he became a professor emeritus at Keio University. His books include “Constitutional Revision and Deterioration” (Jiji Press), “The Truth of Constitutional Revision” (co-authored with Yoichi Higuchi, Shueisha), “Politicians Who Do Not Understand ‘Human Rights’” (Kodansha), and several others.