Better known as a Marxist, the Mexican muralist was a member of the Rosicrucian order AMORC and cultivated other esoteric interests. His wife Frida Kahlo, a staunch Communist, was fascinated by reincarnation.

by Massimo Introvigne

Diego Rivera (1886–1957) and his wife Frida Kahlo (1907–1954) are commonly regarded as quintessential Marxist artists. Yet, they also had an esoteric side, and their connections with esotericism, Rosicrucianism, and Asian religions deserve to be better studied.

The story starts with Rivera’s complicated relationship with one of his early patrons, prominent Mexican intellectual and politician José Vasconcelos (1882–1929), who was Minister of Education in Mexico between 1921 and 1924.

In 1909, Vasconcelos and other young intellectuals had founded El Ateneo de la Juventud in Mexico to oppose both Porfirio Díaz’s (1830–1915) dictatorship and positivism in education. They supported Francisco Madero (1873–1913), who led the Mexican revolution, overthrew Díaz, became president in 1911, and was assassinated in 1913.

Madero was a devoted follower of the brand of Spiritualism, called Spiritism, founded by Allan Kardec (1804–1869) in France. He was part of the Travelers of the Earth, a Mexican Spiritualist movement, and authored a popular Spiritualist manual under the pseudonym “Bhima.” Madero’s political decisions were often influenced by spirits. He was also a Freemason and read Theosophical literature. In his unfinished commentary on the “Bhagavad-Gita” for the Spiritualist journal “Helios,” he argued that Kardecist Spiritualism and original Buddhism and Hinduism were superior to Theosophy, criticizing Madame Helena Blavatsky (1831–1891) for her “pantheism.”

In his “Estudios indostanicos “(1923), Vasconcelos praised Madero’s works on the “Bhagavad-Gita” and criticized Spiritualism and Blavatsky. When Chilean poet and future Nobel Prize laureate Gabriela Mistral (1889–1957) came to Mexico and joined Vasconcelos’ Ministry of Education, he cautioned her against Theosophy. Despite joining the Theosophical Society in 1911, Mistral later accepted some of Vasconcelos’ critiques.

In subsequent years, Vasconcelos acknowledged the validity of certain Spiritualist phenomena, and his theories on races and Atlantis were influenced by Theosophy. He incorporated additional beliefs about Atlantis from Lewis Spence (1874–1955), a Scottish journalist who, despite his criticism of Theosophy, was extensively read within Theosophical circles. When the Minister advised Mistral not to take Theosophy seriously, he was referring to the “yankee” organizational structure of the Theosophical Society in the United States, rather than the Theosophical worldview itself, aspects of which he, in fact, adopted.

Vasconcelos aimed to bolster his position in Mexico and assert regional cultural leadership by connecting with intellectuals interested in esoteric topics. He invited Mistral from Chile and Theosophist poet Porfirio Barba-Jacob (Miguel Ángel Osorio Benítez, 1883–1942) from Colombia to Mexico. Vasconcelos then sent Barba-Jacob to Central America, where he established numerous Theosophical societies in Guatemala, El Salvador, and Honduras.

Vasconcelos played a pivotal role in creating a continental esoteric artistic network. As President of the Mexican National University (1920–21) and Minister of Education (1921–24), he initiated a program to spread modernist ideas through art. Despite his criticism of Marxism, he supported the largely Communist Mexican muralists by providing government walls for their work. He also became Diego Rivera’s key patron, encouraging his return from Paris to Mexico.

Rivera, a promising artist, had been funded by Mexican authorities to study art in Europe from 1907 to 1920. In Paris, he adopted Cubism, Marxism, and atheism while maintaining at the same time some esoteric interests. He was influenced by Theosophy through his friendship with Piet Mondrian (1872–1944), whom he called his closest friend besides Pablo Picasso (1881–1973). Rivera and Mondrian lived in the same building in Paris in 1912–13. Rivera also befriended Adolfo Best Maugard (1891–1964) a Mexican artist interested in Theosophy, who later became director of Mexico’s National Department of Art Education.

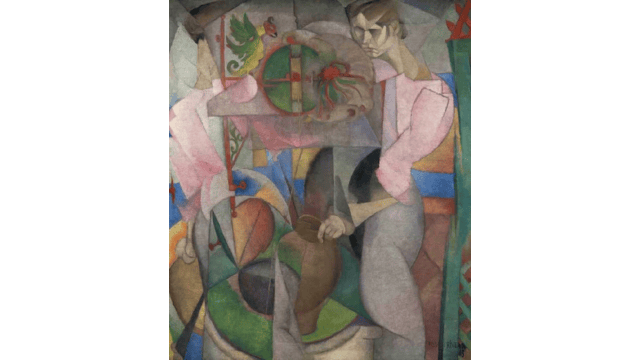

In 1977, Rivera’s highly symbolic painting “La Mujer del pozo” (Lady of the Well, 1913) was found behind his 1915 Cubist work “Zapatista Landscape,” revealing his interest in esotericist during his Paris years.

Rivera continued to incorporate esoteric elements after returning from France to Mexico. Some scholars have noted that despite his Marxist views, many of Rivera’s murals contain esoteric themes. His interpretation of ancient Mexican mythology was influenced more by local new religious movements than by archeology. The first mural he painted in 1922, commissioned by Vasconcelos at the former College of Saint Ildefonso, titled “La Creación,” depicted cosmic energy flowing in multiple directions.

Mexican scholar Susana Pliego Quijano noted that Diego Rivera’s murals in Mexico’s National School of Agriculture (1923–1927) featured Marxist symbols alongside elements from esoteric literature, particularly from Rosicrucian organizations in Mexico. She also identified similar esoteric references in the works of “Dr Atl” (Gerardo Murillo, 1875–1964), a former teacher of Rivera, who once envisioned an “ideal city” for artists, scientists, and wisdom seekers, though the project was never realized.

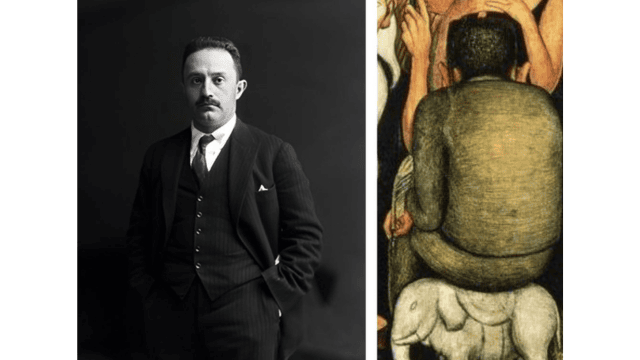

Vasconcelos gave Rivera significant commissions in Mexico, but they later fell out. In 1927, after Vasconcelos left office, Rivera depicted him on a white elephant in a Ministry of Education mural as a Marxist critique of his “Theosophical” and escapist tendencies.

Rivera disagreed with Vasconcelos’ esotericism but did not abandon alternative spirituality. He found Rosicrucianism more compatible with Marxism. In 1926, Rivera helped establish the Quetzalcoatl lodge of AMORC in Mexico City, founded by Harvey Spencer Lewis. He also painted a Quetzalcoatl for its temple.

In 1954, Rivera sought readmission into the Communist Party and had to justify his activities with AMORC. Communism was hostile to Freemasonry, and Rivera defended himself by claiming he joined AMORC, which was not a Masonic organization, to infiltrate it for Communism. He also described AMORC as materialist, focused on energy and matter, and based on ancient Egyptian occult knowledge he presented as a precursor of dialectic materialism.

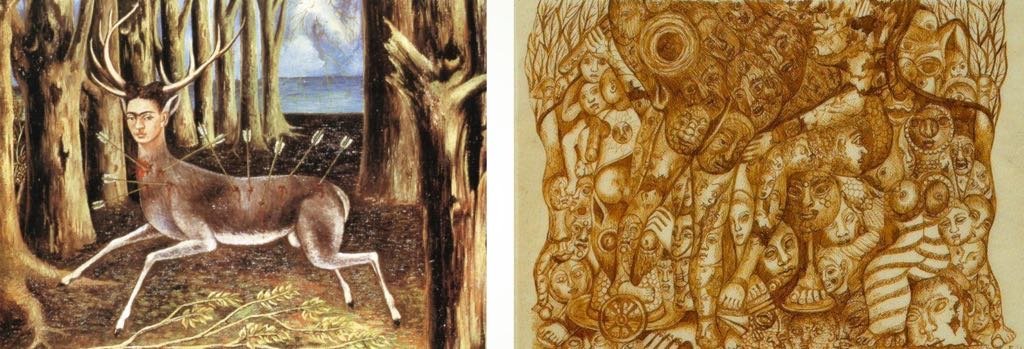

Frida Kahlo (1907–1954), Rivera’s third wife, was a staunch Marxist materialist with no interest in religion. However, her later works featured Eastern and esoteric symbols like Buddha and the Third Eye.

She was fascinated by ancient Egyptian religion and interested in karma and reincarnation. In her “carma” [sic] series, she combined Christian, Hindu, and Aztec symbols to express her desire to overcome suffering and achieve spiritual release while referencing reincarnation and the cycle of earthly suffering.

Frida’s life of physical and moral suffering is well-known. Less well-known is that she explored reincarnation as a possible source of hope.

Massimo Introvigne (born June 14, 1955 in Rome) is an Italian sociologist of religions. He is the founder and managing director of the Center for Studies on New Religions (CESNUR), an international network of scholars who study new religious movements. Introvigne is the author of some 70 books and more than 100 articles in the field of sociology of religion. He was the main author of the Enciclopedia delle religioni in Italia (Encyclopedia of Religions in Italy). He is a member of the editorial board for the Interdisciplinary Journal of Research on Religion and of the executive board of University of California Press’ Nova Religio. From January 5 to December 31, 2011, he has served as the “Representative on combating racism, xenophobia and discrimination, with a special focus on discrimination against Christians and members of other religions” of the Organization for Security and Co-operation in Europe (OSCE). From 2012 to 2015 he served as chairperson of the Observatory of Religious Liberty, instituted by the Italian Ministry of Foreign Affairs in order to monitor problems of religious liberty on a worldwide scale.