From 2018, new regulations have made life for religions increasingly difficult.

by Karine Martin*

*An adapted pre-publication excerpt from “Monastic Daoism Transformed: The Fate of the Thunder Drum Lineage” (2025),available from Three Pines Press.

Article 2 of 4. Read article 1.

In 2018, the State Council, the government’s administrative authority, passed regulations on religious affairs that restricted religious schooling and the times and locations of religious celebrations. Unlike before, any major event or festival now not only has to be registered for approval but attendance is limited to a few hundred, and all participants have to provide identification to government officials. For example, in December 2023, “authorities tried hard to contain and curb Christmas celebrations inside and outside churches, prohibited students and others from participating in Christmas activities and detained some house church leaders to prevent them from organizing congregational gatherings.”

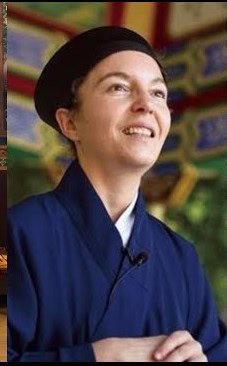

Along other lines, clergy are required to attend indoctrination courses on a regular basis that severely limit the time they can spend on the upkeep of their institutions and/or personal cultivation practice. Also, in September 2023, the Chinese government released a draft regulation that, if passed, would penalize those who wear clothes in public that “hurt the Chinese people’s feelings,” including vestments or religious robes regulations, as Tirana Hassan notes. Along the same lines, contact with foreigners is actively discouraged and can lead to repercussions.

In early 2020, the government intensified the campaign and installed new regulations that require religious groups to accept and spread CCP ideology and values. All clergy have to modify their teachings to that they reflect socialist values and include “Xi Jinping Thought,” an abbreviation of the more formal “Xi Jinping Thought on Socialism with Chinese Characteristics for a New Era” (Xi Jinping xin shidai zhongguo tese shehui zhuyi sixiang 習近平新时代特色社會主義思想). Expressed in detail at the 19th CCP Congress in 2017, this involves fourteen commitments that all center around ensuring that the Party retains and even intensifies its leadership over all forms of work and thought in China. In this context, administrators plan to issue newly annotated versions of key religious scriptures, such as the Quran, that will help teachings align with what they call “Chinese culture in the new era.”

Other regulations limit the organizational competence of religions. Permits for renovation, expansion, or new construction of worship halls and community centers are almost impossible to get and even if a building is completed in perfect alignment with all the regulations, authorities can (and do) order it to be torn down at a moment’s notice. Donations have been severely curtailed, and religions are not allowed to receive funding from sources other than those approved by the state.

Then again, all communications are closely monitored. As Tirana Hassan says, “Through laws and regulations, criminal punishment, harassment, intimidation, and the use of technology, the Chinese government operates one of the world’s most stringent censorship regimes.” China’s online search platforms use 60,000 rules to censor online content; the most far-reaching political censorship among web search engines is by Microsoft’s Bing, its rules less numerous but broader and affecting more search results than those applied by Chinese companies such as Baidu. Under these conditions, religious organizations are severely limited in what they can publish and in some cases are no longer able to post information on social media, such as WeChat.

At the same time, academics in religious studies not only have to submit all teaching content for government approval but are highly restricted in terms of publication, as most venues have closed down. Books with religious content are destroyed en masse. Also, many universities are closing their religion departments, moving their faculty into philosophy or sociology.

In September 2023, even stricter laws were installed that required religious sites and activities to support Sinicization policies, which included prohibiting religious activity if it could “endanger national security, disrupt social order, or damage national interests.” Meanwhile, in Hong Kong, where religious groups are not required to register with the government, religious figures are facing tighter scrutiny and have increased self-censorship under the 2020 national security law.

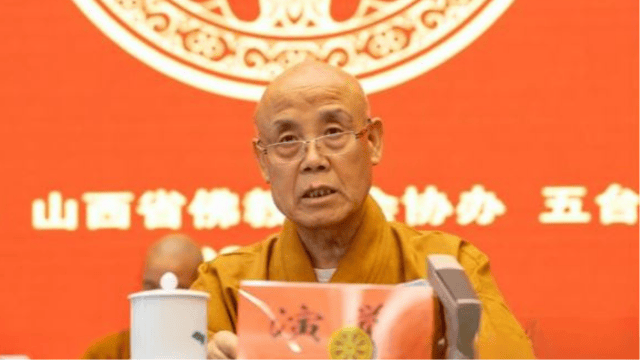

To comply with the regulations, religious organizations tend to hold workshops and training courses to set the agenda for their adaptation. For example, as Zhao Zhangyong described it in “Bitter Winter,” on September 5, 2023, the China Buddhist Association, which is very eager to comply, arranged for a special training course on Mount Wutai, a major sacred mountain with numerous temples. It convened over a hundred Buddhist leaders from all over the country together with the always-present leaders of the United Front Work Department. Based on Xi Jinping’s 2021 speech at the National Conference on Work Related to Religious Affairs, four sets of instructions were formulated to be implemented in all communities.

First, “improve ideological understanding and consolidate the responsibility for a strict management of education,” which means that Marxism and Xi Jinping Thought should be taught to all monks and devotees. Second, “carry out in-depth socialist legal education,” that is, teaching and enforcing all the new laws and directives on religion. Third, “strengthen system management” and build a bureaucracy from the top down to supervise even the most remote temples and their teachings and activities in accordance with the new administrative measures that are essentially aimed at converting all churches, mosques, and temples into centers of CCP propaganda. Fourth, “Sinicize academic courses on Buddhism” by making sure that they apply Xi’s principles and use Marxism as an interpretive tool for religious history and doctrine.

Even more new regulations enacted in 2024 stipulate that religious adepts must “practice the core values of socialism” and “adhere to the direction of the sinicization of religions” (art. 5). Whether places of worship are being “built, renovated, expanded, or rebuilt,” they should “reflect Chinese characteristics and style in terms of architecture, sculptures, paintings, decorations, and so on” (art. 26). The revisions also impose new requirements before religious institutions can apply to create places of worship (art. 20) as well as more stringent restrictions and cumbersome approval processes for building, expanding, altering and moving them (articles 22, 25). In addition, all places of worship must “deeply excavate the content of [religious] teachings and canons that are conducive to social harmony… and interpret them in line with the requirements of contemporary China’s development and progress and in accordance with the excellent traditional Chinese culture” (art. 11).

Beyond that, the regulations prohibit religious education other than government-approved groups (art. 13). Religious institutions need to “operate any schools with Chinese characteristics” (art. 14), which includes “cultivating patriotic religious tenets” and interpreting sacred texts “in the correct manner” (art. 15). The chapter also imposes new requirements that religious establishments must report and seek permission from the authorities to conduct religious training (art. 8) and to organize “large scale religious activities” (art. 42). The 2024 revisions empower grassroots CCP cadres to monitor society. Cadres in “village committees” and “neighborhood committees” must report to the authorities if they discover “illegal religious organizations, illegal preachers, illegal religious activities, or the use of religion to interfere in grassroots public affairs” (art. 7). These surveillance powers at low levels make repression widespread, matching Xi’s “mass mobilization” style of governance and social control, a style that Chinese state media say is directly inspired by Mao Zedong, whose picture is increasingly installed in religious venues.

Karine Martin holds doctorates in both Pharmaceutical Sciences (1997) and Religious Studies (2015). While working in neuroscience research in London, she came in contact with Daoism of the Thunder Drum lineage and entered its training. From 2001 to 2016, she lived in Daoist temples of various regions. She is the founder and director of the French Daoist Association, which organizes lectures, workshops, and training courses. A major representative of Daoism in the West, she presents at international conferences, has a strong internet presence, and is interviewed frequently.