The world-famous astrologer and member of the Theosophical Society was also a gifted painter and participated in significant 20th-century artistic movements.

by Massimo Introvigne

Dane Rudhyar (1895–1985) was the most famous astrologer of the 20th century. While his work as composer of cutting-edge contemporary music has been studied, less known outside the circle of his followers is that Rudhyar was also a painter and a participant in significant artistic movements.

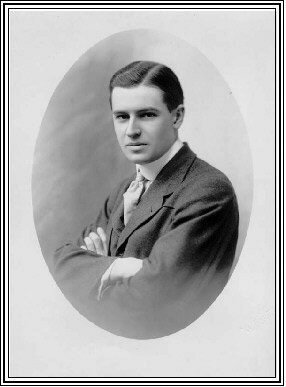

Rudhyar was the pseudonym of Daniel Chennevière, born in Paris on March 23, 1895. His poor health as a teenager turned him to meditation and music. He was a bright pupil of the Paris Conservatory but soon realized that the ultra-modern music he was interested in was not popular in France. He thus moved to New York at age 21, in 1918, where some of his pieces were performed. There, he developed an interest in Zen Buddhism and esotericism.

In 1920, he was asked by the American branch of Adyar’s Theosophical Society to compose music for their events. This was one of the reasons he moved to California, where he was admitted as a member of the Society in the same year 1920. He acquired an encyclopedic knowledge of Theosophy’s classics and in subsequent years will become a frequent lecturer at Theosophical Society’s lodges across the United States and contributor to its magazines. Although he befriended the members of the splinter Theosophical group Temple of the People headquartered in Halcyon, California, and was a key participant in their gatherings, he always remained a member of the Adyar-affiliated American Theosophical Society, later called from 1934 the Theosophical Society in America.

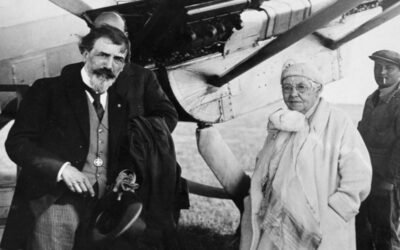

Throught the Theosophical Society, Rudhyar met Marc Edmund Jones (1888–1980), one of the fathers of American astrology. Jones became a member of the Theosophical Society in 1941 but wrote that he regarded himself as “a Theosophist of interest if not affiliation” since he was 18 years old. It was through Jones that Rudhyar became a serious student of astrology, eventually emerging as the most prominent astrologer of his generation. His book “The Astrology of Personality” (1936) is considered the founding manifesto of transpersonal and humanistic astrology. He acknowledged his debt to Madame Helena Blavatsky (1831–1891) and Theosophy in formulating its key concepts.

While he was a popular lecturer in Theosophical and esoteric circles, Rudhyar did not completely solved in the United States the problem of finding an audience for his brand of contemporary music. There was a niche community of fellow musicians experimenting in similar directions, but concert halls and larger audiences found their music dissonant and unpleasant. While he never abandoned composition, he decided that the visual arts offered better possibilities for conveying Theosophical and esoteric ideas to a larger audience.

He later wrote in his autobiography that “If I had been able to pursue my musical activities and if performances of my compositions had been possible, I most likely would not have started to paint.” Because communicating through music continued to be difficult, he devoted increasing energies to painting since he started spending time in 1938–39 in New Mexico, which hosted a significant colony of artists. Most of them were directly or indirectly connected with Russian painter and Theosophist Nicholas Roerich (1874–1947) and the revelations he claimed to receive from the Masters. Among the artists Rudhyar associated with in New Mexico were Emil Bisttram (1895–1976), Lawren Harris (1885–1970), the best-known Canadian painter of the twentieth century and a very active member of the Theosophical Society, and Raymond Jonson (1891–1982), one of the American friends of Roerich.

Together, they founded he Transcendental Painting Group (TPG) in 1938. The legal structure supporting the TPG was called American Foundation for Transcendental Painting. Rudhyar served as one of its Vice Presidents.

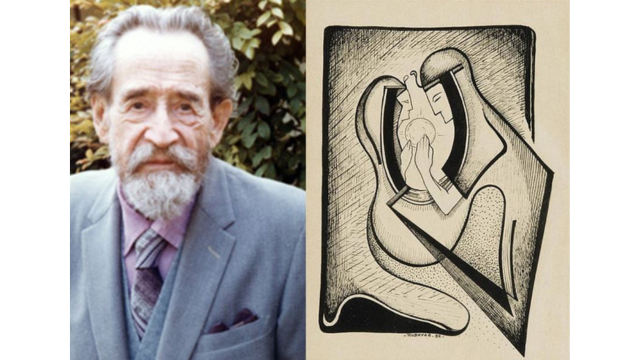

Rudhyar was more than a mere amateur and both his theoretical and administrative roles in the TPG were important. The quality of his paintings and drawings was recognized by his fellow artists, and they made their way to important art galleries. In October 1947, Raymond Jonson organized an exhibition of thirty-five paintings by Rudhyar at the University of New Mexico in Albuquerque, where he was teaching. Rudhyar continued to paint almost to the end of his life. The festivals organized in his later years to celebrate him as an astrologer often featured exhibitions of his paintings.

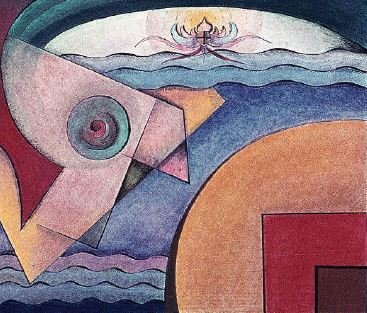

While the 1952 drawing “The Magnet of Love” epitomized the esoteric belief in the Law of Attraction, he regarded works such as “Power at the Crossroads” (1938), in which we can also see the influence of Jonson and Bisttram, as produced under the influence of mysterious higher powers.

At the 1947 Albuquerque exhibition, Rudhyar posted a manifesto summarizing his ideas about art. Under the title “Art as Evocation,” he wrote that, “My aim in the arts is essentially to bring to an objective focus, and to release through significant forms some aspects of the creative process of human evolution which are radically transforming our society and our civilization. We are everywhere in the midst of a metamorphosis of human consciousness, whose frontiers are gradually extended in an attempt to include men of all races and cultures. The frontiers of the arts must likewise be pushed into deeper as well as higher regions, so that forms (and tones or gestures) may be produced that will make concrete and visible the very core of this transforming and renewing activity of the human spirit.”

Rudhyar saw a new civilization emerging, which “postulates a deep-seated renewal of the typically European or even Western way of seeing, perceiving, thinking, feeling, evaluating which, in the main, are no longer convincing or creative, in spite of all attempts at neoclassicism and neo-everything. A new sense of order is required; an order far more inclusive than the old medieval or classical traditions have known, because man’s experience is today (potentially at least) also far more inclusive. New forms are needed to incorporate the challenges of a new social and psychological environment, and the answers of creative men to these challenges.”

What Rudhyar wanted to create was an art that would be evocative rather than decorative. “This distinction between evocative and decorative art,” he wrote, “depends primarily on what the creative artist, consciously or unconsciously, puts into his creation (i.e., their inherent human worth and meaning, but not any so-called ‘literary’ contents); it is much less concerned with whether it uses natural forms or geometrical patterns as a foundation… Far more than to give esthetical pleasure or a feeling of technical problems overcome. I seek to participate in the creation of a new civilization, by evoking through form, color and rhythm such ideas, feeling and vistas of inner reality as may contribute to a renewal of human values and human perceptions on the basis of a fuller realization of spirit, in me and in all men.”

Massimo Introvigne (born June 14, 1955 in Rome) is an Italian sociologist of religions. He is the founder and managing director of the Center for Studies on New Religions (CESNUR), an international network of scholars who study new religious movements. Introvigne is the author of some 70 books and more than 100 articles in the field of sociology of religion. He was the main author of the Enciclopedia delle religioni in Italia (Encyclopedia of Religions in Italy). He is a member of the editorial board for the Interdisciplinary Journal of Research on Religion and of the executive board of University of California Press’ Nova Religio. From January 5 to December 31, 2011, he has served as the “Representative on combating racism, xenophobia and discrimination, with a special focus on discrimination against Christians and members of other religions” of the Organization for Security and Co-operation in Europe (OSCE). From 2012 to 2015 he served as chairperson of the Observatory of Religious Liberty, instituted by the Italian Ministry of Foreign Affairs in order to monitor problems of religious liberty on a worldwide scale.