The About-Picard law is a failed and wrong statute that should be repealed in France rather than exported abroad.

by Massimo Introvigne

Opponents of the Unification Church/Family Federation for World Peace and Unification who use or, rather, misuse the assassination of former Prime Minister Shinzo Abe to claim that legal measures against “cults” are needed, suggest that something similar to the French About-Picard law of 2001 should be introduced in Japan.

I was very much part of the discussions surrounding the adoption of the controversial law, but they happened more than two decades ago. What the About-Picard law is all about, and how it emerged, needs to be shortly explained. In 1994, 1995, and 1997 an esoteric new religious movement known as the Order of the Solar Temple organized a series of mass suicides and homicides that claimed several dozen lives in Switzerland, France, and Quebec. The incidents generated an enormous emotion in France, because many of the victims were French and some of the group’s members were wealthy professionals, making it difficult to dismiss their story as one typical of “marginal cults.”

In France, after the first Solar Temple suicides and murders, a Parliamentary commission to investigate “cults” (called in French “sectes”) was set up. It released its report in December 1995. Its two main recommendations were to institute an inter-ministerial agency for combating “cults,” and to pass a new anti-cult law. The agency was created in 1996. It had various incarnation up to present-day MIVILUDES, the Inter-ministerial mission for monitoring and combating cultic deviances (dérives sectaires).

MIVILUDES publishes periodically reports on “cults” that receive a good deal of criticism for their vagueness and lack of rigor. For instance, the Mission has recently admitted that its figures of 500 “cults” and 500,000 “victims of the cults” in France, which it often repeats and are quoted in the media, come from old texts of 1995, 2006, and 2010, which were already controversial when they were published, are not even quoted correctly in the MIVILUDES’ reports, and of course refer to more than a decade ago.

The methodology of MIVILUDES is based on the “saisines” concerning various “cults” it receives every year. The “saisines” are alerts by those who write to the MIVILUDES, or use a web form, to denounce a “cultic deviance.” We objected that there is no verification that those sending a “saisine” to the MIVILUDES exist, let alone tell the truth, and mentioned the case of an American scholar who had successfully registered with the French governmental mission a “saisine” signed by Napoleon Bonaparte.

In 2022, the MIVILUDES admitted that “saisines” are not “reports” of identifiable “cultic” abuses. They include any interaction between the MIVILUDES and public and private subjects. That the MIVILUDES does not provide either scientifically valid or objective information about “cults” should be, by now, obvious.

Introducing a law against “cults” in France proved more difficult than creating a specialized agency. How can a “cult” be identified and distinguished from a legitimate religion? French politicians consulted various experts, some genuine and some self-styled. Some Christian enemies of “cults” suggested to define the “cults” as those professing doctrines regarded as heretic by mainline religions. However, this would obviously have violated the Constitutional principle of secularity, converting the state into a judge of religious doctrines.

The alternative that emerged was to use the main tenet of the anti-cult ideology, i.e., that legitimate religions are joined through an act of free will, while conversions to “cults” are obtained through a mysterious technique variously called “mental manipulation,” “mind control,” or “brainwashing.” The first drafts of the French law created the crime of “mental manipulation,” punished with severe jail penalties.

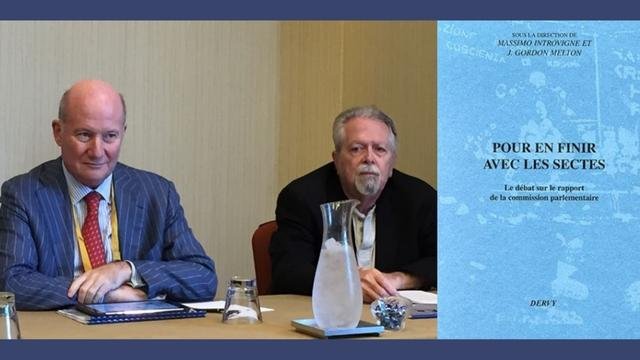

American scholar J. Gordon Melton and the undersigned edited a book called “Pour en finir avec les sectes” (To put an end to the discussion on cults), which went into two editions in 1996 and was quoted by many voices in the institutional and parliamentary debates.

The authors included most of the leading international scholars of new religious movements, who argued that two decades of debate among academics had led to the conclusion that “mental manipulation” or “brainwashing” does not exist. We also pointed out that American case law since the “Fishman” decision by a federal court in California in 1990, as well as decisions in other countries (including Italy), had already recognized that the notion of “mental manipulation” as allegedly practiced by “cults” belongs to the realm of pseudoscience.

Our criticism was also echoed by senior judges and politicians in France, including cabinet ministers. After lengthy discussions, it was decided to eliminate all references to “mental manipulation” from the draft law.

However, pressures by anti-cultists continued, and in the end the law was passed in 2001 incriminating, rather than “mental manipulation,” “techniques likely to impair a person’s judgment” by putting her “in a state of psychological… subjection.” Senator Nicolas About and MP (and anti-cult activist) Catherine Picard persuaded a majority of their colleagues that this was something different from the criticized “mental manipulation” or “brainwashing.” Critics objected that it wasn’t.

Under the About-Picard law, members of religious movements using these “techniques” are punished with three years of imprisonment, leaders with five years. The movements themselves may be legally dissolved.

The About-Picard law was passed in 2001. In 2011, in its tenth anniversary, Susan J. Palmer, a well-known Canadian scholar of new religious movements, published with Oxford University Press the book “The New Heretics of France.” Palmer reviewed the international criticism of the About-Picard law, and presented the results of a detailed study of how it had been enforced. She updated it in conference papers presented in 2022, with similar results.

In short, she found that the law was strong with the weak, and weak with the strong. It led to the conviction and imprisonment for having used “techniques creating a state of psychological subjection” of the leaders of several small groups, most of them with only a few dozen followers. While anti-cultists had proclaimed the law would destroy the organizations they denounced as stereotypical “cults” such as the Church of Scientology or the Jehovah’s Witnesses, in fact it was never successfully enforced against them, nor against any large group with thousands of devotees.

The reason this happened is that, to avoid mentioning the discredited concept of “mental manipulation,” a vague category of “techniques creating a state of psychological subjection” had been introduced. Either these “techniques” are the same as “mental manipulation” or “brainwashing,” and fall under the criticism scholars have directed against these categories, or it is unclear what they are. Good lawyers, supported by good experts, can easily prove that using the “techniques” mentioned in the About-Picard law is an imaginary crime. However, the law can be enforced against small groups lacking the resources to hire effective lawyers or the contacts with competent experts.

French anti-cultists blame the fact that the About-Picard law has been unsuccessful on the scholars whom they accuse of being “cult apologists,” or hired guns for the “cults.” In fact, they created a caricatural image of these scholars, claiming that they defend all religious groups, guilty or innocent, and dogmatically believe that “cults” never commit crimes.

Perhaps these scholars exist, but I have never met one. On the contrary, the scholars I know maintain that religious groups and individuals who commit common crimes, both part of traditional religions (such as pedophile priests or terrorists who claim to act in the name of Islam) and of new religious movements, should be prosecuted and sentenced. Common crimes include homicide, physical violence, rape, sexual abuse, and so on. They are different from imaginary crimes such as “being a cult” or “using techniques aimed at psychological subjection.”

To prosecute religious (and non-religious) groups and individuals that commit real crimes, no special law is needed. Special laws only create dangers for religious liberty and, by confusing the issues, make it more difficult to prosecute the real crimes. Twenty years of the About-Picard law abundantly prove it. It is a failed and wrong model. Progress would be made by repealing it in France, certainly not by exporting it to other countries.

Massimo Introvigne (born June 14, 1955 in Rome) is an Italian sociologist of religions. He is the founder and managing director of the Center for Studies on New Religions (CESNUR), an international network of scholars who study new religious movements. Introvigne is the author of some 70 books and more than 100 articles in the field of sociology of religion. He was the main author of the Enciclopedia delle religioni in Italia (Encyclopedia of Religions in Italy). He is a member of the editorial board for the Interdisciplinary Journal of Research on Religion and of the executive board of University of California Press’ Nova Religio. From January 5 to December 31, 2011, he has served as the “Representative on combating racism, xenophobia and discrimination, with a special focus on discrimination against Christians and members of other religions” of the Organization for Security and Co-operation in Europe (OSCE). From 2012 to 2015 he served as chairperson of the Observatory of Religious Liberty, instituted by the Italian Ministry of Foreign Affairs in order to monitor problems of religious liberty on a worldwide scale.