Being a citizen and a “full citizen” is different. The failure of transitional justice in Taiwan means that Tai Ji Men dizi are not really recognized as “full citizens.”

by Daniela Bovolenta

*A paper presented via video at the International Forum on World Citizenship Day 2025 “Transitional Justice Through Effective Relief: The Tai Ji Men Human Right Case,” Taipei, April 1, 2025. See full videos of the morning session and of the afternoon session of the Forum.

We read often that the idea of citizenship dates back to the ancient city-states of Greece. However, it was something different from modern citizenship. The legal citizenship was connected to freedom, but not everybody was free. Greek city-states had slaves, who were not citizens. Women had very few rights, and certainly did not have the rights of male citizens.

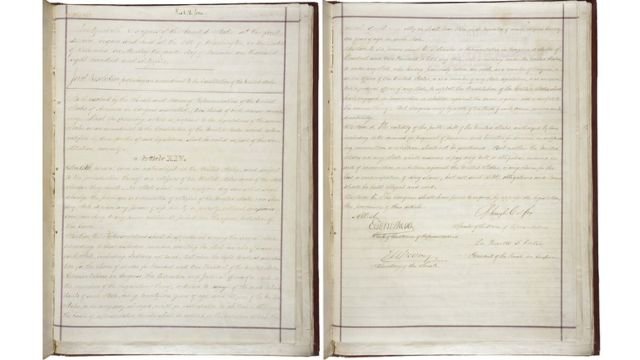

Modern political science has introduced a distinction between “citizens” and “full citizens.” In modern democratic societies, the clearest case is the one of minors. Minors are citizens of a country if at least one of their parents is a citizen. This is known as “ius sanguinis,” the right of the blood. In some countries, there is also a “ius soli,” meaning that it is enough to be born in a country to be a citizen of it. This is in the 14th amendment added to the US Constitution in 1866. However, President Trump is now arguing that “ius soli” does not apply to those born in the United States whose parents are illegal immigrants. The matter will probably be solved by the Supreme Court.

At any rate minors are citizens, but they are not “full citizens.” They do not enjoy the full rights of self-determination, for obvious reasons, nor the political rights of voting or running for office.

While few would object to the fact that minors do not enjoy the full rights of citizenship, the problem is different for other categories that were and are denied “full citizenship” in some countries. Women, for example, were subject to limitations, excluded from certain professions, and not allowed to vote before the 20th century and somewhere well into the 20th century as well. Not only in South Africa during the sad days of the apartheid, but also in certain states of the United States, it was only in the late 20th century that restrictions to citizenship based on the color of the skin disappeared. Before this happened, women and black were not “full citizens.”

It is typical of non-democratic states that other categories are denied “full citizenship” based on their religious or political opinions. In particular, there are religious minorities whose members are banned, blacklisted, and not allowed access to a whole series of citizens’ rights. This may happen explicitly—through lists of “heterodox,” “extremist,” or undesirable religious and spiritual organizations, which exist in China and Russia, or the laws against the Ahmadis in Pakistan and the members of the Baháʼí Faith in Iran—or implicitly.

During the Martial Law era in Taiwan, those who opposed the regime did not really enjoy full citizenship. But in practice even in the subsequent post-authoritarian phase groups of Taiwanese nationals were still denied full citizenship. This was the case for persecuted spiritual and religious minorities. After the Tai Ji Men case started in 1996, in practice Tai Ji Men dizi (disciples) were denied full citizenships as some of their basic human rights were violated.

When authoritarian and post-authoritarian regimes are replaced by democracy, full citizenship should be restored to those who were unfairly denied it. This is the aim of transitional justice. In theory, there are provisions about transitional justice in Taiwan. In practice, they do not entirely work because they only deal with violations of human rights perpetrated before November 6, 1992. They thus ignore the post-authoritarian period after that date, including the human rights violations that happened during, or were caused by, the politically motivated religious crackdown of 1996.

This is not acceptable and means that entire categories are still denied full citizenship as transitional justice is not applied to them. At best, they are second class citizens. It is the case of the Tai Ji Men dizi. They may legally be citizens, but in practice they do not enjoy full citizenship.

This situation is not tolerable. The Tai Ji Men case should be solved. Full citizenship rights should be restored to Tai Ji Men. And the time to act is now.