Reportedly, Chairman Mao’s eldest son was killed in the Korean War after he gave away his position by cooking egg-fried rice. The dish is thus becoming dangerous.

by Zhou Kexin

Don’t talk about egg-fried rice in November in China. Avoid also October. Better still, err on the side of caution and never ever mention the dish. Even a celebrity chef such as Wang Gang had to publicly apologize on November 27, hours after posting a video presenting his recipe for egg-fried rice. This is unofficially but very effectively prohibited in China in November, some say also in October. Breaching the unwritten rule can destroy a career. To be on the safer side, Wang—who had been involved in egg-fried rice controversies before—promised “to never again make egg-fried rice, nor make any videos about it.”

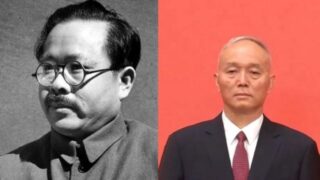

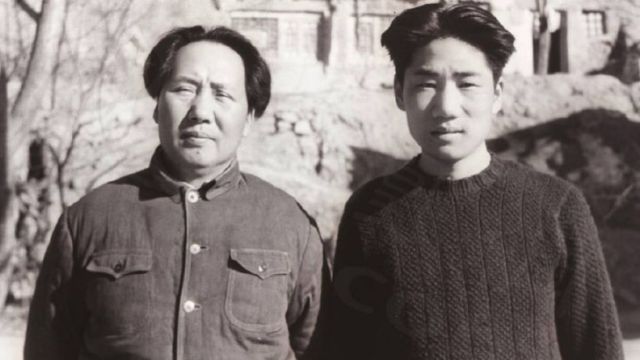

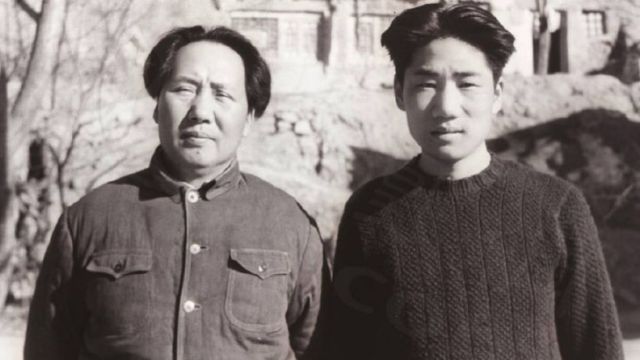

Non-Chinese readers of “Bitter Winter” may not understand what it was all about. It all started with a historical event that perhaps never happened. On November 25, 1950, Mao Anying, the eldest son of Chairman Mao, was killed in an American bombing during the Korean War. Rumors immediately spread that the younger Mao had missed his breakfast and, breaching military security rules, had started cooking egg-fried rice in the open, thus giving away his position. That Mao Anying was killed in the Korean War is certainly true, although the lack of transparency in CCP’s communication led to speculations about what really happened. The egg-fried rice tale is probably apocryphal.

The story is not unimportant. Many believe that the death of Mao Anying changed the course of Chinese history. Had he survived, it is argued that Chairman Mao planned to make him his successor, inaugurating a dynastic leadership of the Communist Party similar to the system implemented in North Korea by Kim Il-Sung and his successors. There are other, probably unfounded rumors that rival CCP leaders, rather than egg-fried-rice, caused the death of Mao Anying.

Be it as it may be, some anti-Mao dissidents started celebrating a “Chinese Thanksgiving Day” on November 25, honoring by eating egg-fried rice the incident that freed China from the perspective of a North-Korean-style dynastic Communist rule. Not surprisingly, the CCP reacted by repressing any reference to egg-fried rice on November 25 and in fact during the entire month of November—sometimes also in October, the month of Mao Anying’s birthday (he was born on October 24, 1922).

The fact is that these are old stories and some young Chinese may no longer remember them. They can thus become dissidents without knowing it, just by praising egg-fried rice in October or November. Old Chinese novels told how travelers should learn the difficult art of avoiding highwaymen who might easily kill them. Avoiding the intricacies of CCP censorship may prove today even more difficult.