A new book discusses how Xi Jinping’s regime uses Buddhism as a cultural and propaganda resource, and Buddhist communities try to take advantage of it.

by Massimo Introvigne

In “Metamorphosis of Buddhism in China’s New Era: Between State, Culture and Religion” (London: Bloomsbury Academic, 2025), editors Yoshiko Ashiwa, David L. Wank, and Ji Zhe assemble a rich tapestry of essays that illuminate the evolving landscape of Chinese Buddhism in the post-Mao era. Drawing on extensive fieldwork and multidisciplinary expertise, the volume offers a panoramic view of how Buddhist institutions, practices, and identities have adapted to the shifting contours of state ideology, market forces, and cultural nationalism.

The book’s strength lies in its diversity. Eleven chapters traverse temples, nunneries, scenic areas, mega-expos, and lay communities, revealing the ingenuity with which Buddhist actors navigate the constraints and opportunities of China’s “New Era.” The contributors—anthropologists, sociologists, historians, and religious studies scholars—bring granular insight to phenomena often flattened by political discourse.

The opening chapter by Ashiwa, Wank, and Zhe sets the analytical framework, tracing Buddhism’s metamorphosis from suppression during the Cultural Revolution to its strategic rehabilitation as part of “traditional Chinese culture” under the Communist Party’s cultural policy since 2002. This framing is essential: it reminds readers that Buddhism’s revival is not merely spiritual but deeply political.

Ester Bianchi’s chapter on Theravāda meditation at Shifo Temple, a Sichuan nunnery, stands out. It shows how Mahāsati Vipassanā techniques—originating in Thailand—were recontextualized within Han Chinese Mahāyāna settings. The transnational flow of practice was tolerated until 2023, when the nuns had to leave after the authorities refused to recognize the temple legally. However, Mahāsati continues to be taught elsewhere.

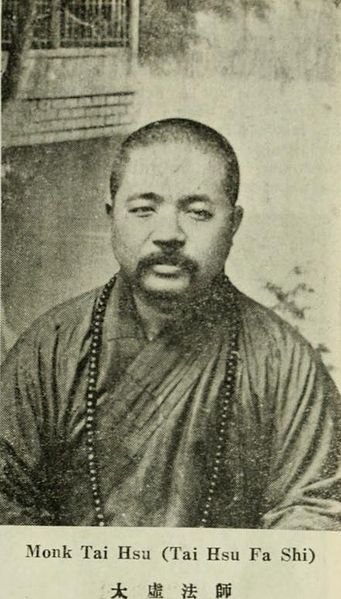

Yoshiko Ashiwa and David Wank revisit Taixu’s vision of Buddhist academies, examining how his modernist aspirations are selectively revived in contemporary China. Their analysis underscores the tension between universalist ideals and nationalist appropriations of Buddhist heritage.

Amandine Péronnet’s study of Pushou Temple on Mount Wutai, Shanxi, explores how Vinaya rules are updated through volunteerism and managerial innovation. The temple becomes a site of negotiation between tradition and (politicized) modernity, with lay participation reshaping monastic boundaries.

Xu Lufeng’s chapter on Shaolin Temple is particularly compelling—though now unintentionally ironic. Written before Abbot Shi Yongxin’s July 2025 arrest for embezzlement and misconduct, the chapter acknowledges his achievements in branding “Wushu Chan” and globalizing Shaolin culture. Xu’s analysis of Shaolin’s fusion of martial arts, tourism, and Chan Buddhism is incisive. Still, the recent scandal casts a shadow over the temple’s commercial success and raises questions about the spiritual cost of state-aligned entrepreneurship.

Catherine Hardie’s chapter on the Larung Gar Internet textual community offers a rare glimpse into Sinophone Tibetan Buddhist lay education. Her ethnography reveals how Tibetan teachings are digitally adapted for Han audiences, creating hybrid devotional spaces. As part of the well-documented repression of Tibetan Buddhist institutions and figures, also affecting Larung Gar, the Chinese authorities put a halt to this Internet activity in the late 2010s. The leading association of the textual community was declared illegal in 2019, and its website was shut down.

Ji Zhe’s exploration of rituals for aborted fetus spirits is both sensitive and provocative. He shows how new ritual forms, which have also been studied in Japan and elsewhere, emerge to address moral anxieties and social trauma, blending Buddhist compassion with cultural pragmatism.

Weishan Huang’s analysis of nunnery relocation in Shanghai examines how urban redevelopment reshapes religious geography. The temple becomes a “social abstraction,” its spiritual function subordinated to bureaucratic and commercial logics.

Utirauto Otehode and Paul Farrelly’s chapter on Famen Temple’s transformation into a “Buddha Culture Scenic Area” in Baoji City, Shaanxi, illustrates the blurring of sacred and secular space. The commodification of relics and ritual is not merely tolerated—state and corporate actors orchestrate it.

Guillaume Dutournier’s study of another scenic area in Jincheng City, Shanxi, shows how Buddhist symbolism is co-opted for political messaging and tourist appeal. The fusion of religious and commercial narratives produces a new kind of public religiosity—one that is legible to the state and palatable to consumers.

The final chapter by Ashiwa and Wank on three Buddhist fairs in Xiamen reveals how Buddhism enters the global market as both commodity and cultural diplomacy. The fair becomes a stage for showcasing “authentic” Chinese Buddhism, curated for international audiences.

Yet for all its richness, the volume has blind spots, although we should consider that it does not claim to offer a complete map of Buddhism in China. The editors acknowledge the role of the China Buddhist Association (CBA) in regulating religious life. Still, the book mentions but does not sufficiently address the persecution of Buddhist movements and figures outside the CBA’s purview. Independent monks, underground temples, and government critics face harassment, surveillance, and closure. Tibetan-speaking Tibetan Buddhists, in particular, endure systemic repression—from restrictions on reincarnation to the assault on monastic centers like Larung Gar.

The book’s emphasis on adaptation and innovation risks obscuring the coercive backdrop against which these transformations occur. While the contributors are careful not to romanticize state-Buddhist synergy and duly mention instances of repression, they sometimes underplay the costs of compliance and the silencing of dissent.

In sum, “Metamorphosis of Buddhism in China’s New Era” is a valuable and timely contribution to studying contemporary religion in China. It offers nuanced portraits of Buddhist creativity under constraint, but readers should supplement it with accounts of those who resist the state’s embrace—and pay the price. The metamorphosis is real, but not always voluntary.

Massimo Introvigne (born June 14, 1955 in Rome) is an Italian sociologist of religions. He is the founder and managing director of the Center for Studies on New Religions (CESNUR), an international network of scholars who study new religious movements. Introvigne is the author of some 70 books and more than 100 articles in the field of sociology of religion. He was the main author of the Enciclopedia delle religioni in Italia (Encyclopedia of Religions in Italy). He is a member of the editorial board for the Interdisciplinary Journal of Research on Religion and of the executive board of University of California Press’ Nova Religio. From January 5 to December 31, 2011, he has served as the “Representative on combating racism, xenophobia and discrimination, with a special focus on discrimination against Christians and members of other religions” of the Organization for Security and Co-operation in Europe (OSCE). From 2012 to 2015 he served as chairperson of the Observatory of Religious Liberty, instituted by the Italian Ministry of Foreign Affairs in order to monitor problems of religious liberty on a worldwide scale.