The Spanish artist was the first to react to Hiroshima, and to conclude that the new “atomic era” had something to do with religion.

by Massimo Introvigne

Article 1 of 2.

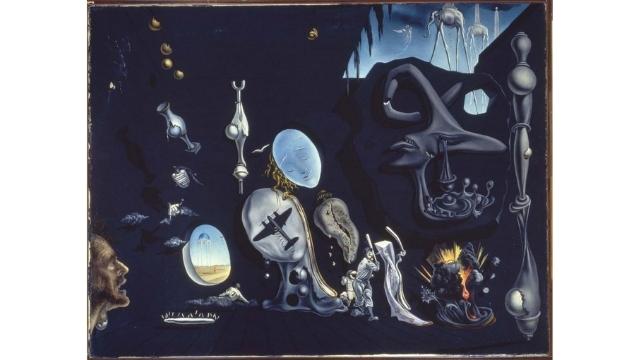

The 2022 exhibition “Surrealism and Magic: An Enchanted Modernity” at Venice’s Peggy Guggenheim Collection takes to Italy a work by Salvador Dalí (1904–1989) that has a special relation with the atomic bomb: “Uranium and Atomica Melancholica Idyll,” from Madrid’s Museo Nacional Centro de Arte Reina Sofía.

We live in times when threats of nuclear war, long regarded as unthinkable, seems to become part of superpower rhetoric. The exhibition of Dalí’s painting in Venice offers an opportunity to reflect on how during the Cold War artists tried to “exorcize” the atomic bomb and, in the process, were often led to reflect on religion.

Italy has a specific tradition of artists reflecting on nuclear weapons. Also because of a sensational court case, this tradition became known also to the non-specialized public. Possibly, the interests culturally savvy Italians increasingly take in campaigns for nuclear disarmament owes something to these artistic precedents.

A possible objection is that the “nuclear art” fashion and the court case both happened some seventy years ago, and that only a cultivated fraction of the Italian population attends art exhibitions and is familiar with artistic currents. However, it is precisely this cultivated segment of Italian citizens who participate in nuclear disarmament events and campaigns, including those promoted by the Buddhist movement Soka Gakkai under the label “Senzatomica.”

Dalí’s “Uranium and Atomica Melancholica Idyll” may well be the first painting by a leading artist following the atomic bombings of Hiroshima and Nagasaki (August 6–9, 1945). “The atomic explosion of August 6, 1945 shook me seismically,” wrote Dalí, and he immediately started the painting.

A first feature of “Uranium and Atomica” we note are the elephants on the upper right. Those who have been close to an elephant know that they drop excrements almost non-stop. This action here is a metaphor of dropping atomic bombs, an act that is as “dirty” as it is tragic.

The obelisks allude to the bloody wars between the Romans and the Carthaginians, and the terror created among the inhabitants of Italy in 218 BCE when Hannibal (247–182 BCE) crossed the Alps with his elephants and invaded the peninsula. Dalí had an interest in Hannibal, as evidenced by his late watercolor “Hannibal Crossing the Alps,” now at The Dalí Museum in St. Petersburg, Florida. The meaning of the allusion in “Uranium and Atomica” is that the horrors of war always repeat themselves.

In “Uranium and Atomica” we immediately see the consequences: the nuclear explosion directly invading the human body, and a victim on the left reminiscent of classical depiction of slaves but also deformed by the radiations.

The painting could not omit to mention that it had been the United States that had dropped the bombs in Japan. Dalí disseminated in “Uranium and Atomica” images of quintessentially American boy baseball players. He was aware that “Little Boy” was the codename for the Hiroshima bomb.

After “Uranium and Atomica,” Dalí’s career went through two dramatic changes. First, he broke with Surrealism, claiming that the discontinuity of matter and the dissolution of gravity of atomic physics required an entirely new way of painting.

Second, Dalí, a former anticlerical, reconciled with religion, claiming that the new physics proved a divine design in the universe and called for a “nuclear mysticism.” He was received by Pope Pius XII (1876–1958) on November 23,1948 and showed the Pontiff a first version of his “The Madonna of Port Lligat.”

One main source for Dalí’s idea that the new atomic physics supported a “nuclear mysticism” was the book “Good and the Atom,” published in 1945 by English Catholic priest and theologian Ronald Knox (1888–1957). Dalí decorated the 1948 Spanish translation he owned with drawings of explosions and atoms. This religious enthusiasm, however, should not be misunderstood. Both Knox and Dalí described nuclear weapons as terrifying and sinister, while supporting peaceful research on the atom.

In “Leda Atomica” (1949) Dalí revisited the myth, often portrayed in the Renaissance and beyond, of Zeus mutating into a swan to seduce the Queen of Sparta, Leda (the painter’s wife Gala, 1894–1982). In the painting, Leda is “atomica” in the sense that, in accordance with the new atomic physics, there is no gravity. The figures are dematerialized and float in the air.

In 1950, Pope Pius XII proclaimed the dogma of the Assumption of Mary, i.e., that the Mother of Jesus was taken up to Heaven with her physical body. Dalí wrote in the Catholic journal “Etudes Carmélitaines” that this definition was “the most important historical theme of our epoch” and can only be explained scientifically and represented artistically by his own “nuclear mysticism” and atomic de-materialization and recomposition, as he tried to do with his painting “Assumpta Corpuscularia Lapislazulina” (1952)

In 1951, Dalí had published a “Mystical Manifesto” on his new religious approach to atomic physics and the arts. The “conversion” (although the religious turn of Dalí was more complicated) of a famous former anticlerical artist, his enthusiasm for Pope Pius XII, and his announcement that a new “nuclear art” was coming as the only true modern art were largely covered by media in Italy. Not the Catholic media only: on April 28, 1952, the influential “Corriere Lombardo” of Milan published a lengthy article on Dalí, atomic issues, and the Pope.

This upset some Italian artists, who believed Dalí had stolen the expression “nuclear art” from them, and the matter ended up in Italian and French courts of law (making in the process all the artists involved even more famous). We will discuss these developments in the second article of the series.

Massimo Introvigne (born June 14, 1955 in Rome) is an Italian sociologist of religions. He is the founder and managing director of the Center for Studies on New Religions (CESNUR), an international network of scholars who study new religious movements. Introvigne is the author of some 70 books and more than 100 articles in the field of sociology of religion. He was the main author of the Enciclopedia delle religioni in Italia (Encyclopedia of Religions in Italy). He is a member of the editorial board for the Interdisciplinary Journal of Research on Religion and of the executive board of University of California Press’ Nova Religio. From January 5 to December 31, 2011, he has served as the “Representative on combating racism, xenophobia and discrimination, with a special focus on discrimination against Christians and members of other religions” of the Organization for Security and Co-operation in Europe (OSCE). From 2012 to 2015 he served as chairperson of the Observatory of Religious Liberty, instituted by the Italian Ministry of Foreign Affairs in order to monitor problems of religious liberty on a worldwide scale.