Arnaldo Ginna, a pioneer of Futurism and abstract art, joined the Theosophical Society in 1913. Theosophy profoundly influenced others as well.

by Massimo Introvigne

Article 2 of 5 (published on consecutive Saturdays). Read article 1.

When Futurism emerged in Italy, it quickly attracted artists familiar with Theosophy. The first Futurist painters appeared in Milan in 1910, including Russolo, Umberto Boccioni (1882–1916), and Carlo Carrà (1881–1966). In 1905, the book “Thought-Forms” by Besant and Leadbeater was published in English and French. Although the impact of this book—and Leadbeater’s other work, “Man Visible and Invisible”—on artists has often been exaggerated, Italian musicologist Luciano Chessa and literary historian Simona Cigliana agree that it’s evident Boccioni embraced ideas about expressing feelings through colors from “Thought-Forms.” Boccioni’s writings show some knowledge of occult and esoteric themes. Russolo’s connection to Theosophy is well documented, and Chessa finds passages in Carrà’s writings that “unquestionably reveal associations with Leadbeater.” Yet, he admits this might reflect influences from other Futurists and that Theosophical ideas are more evident “in his theoretical writings than in his paintings.”

Concerning Boccioni, additional evidence was strengthened by the discovery of the original text of a lecture he gave on May 29, 1911, at the International Artistic Association of Rome. In this lecture, he outlined a connection from Previati’s “Rose-Croix” to modern “Spiritualist” (Theosophical) explorations of forms and colors linked to feelings. Boccioni later excised the Previati reference from the published lecture, likely to adhere to Futurist orthodoxy that aimed to distance itself from Symbolism. During this period, Boccioni began working on his “Stati d’animo” (States of Mind, 1911–12). In the same year, Russolo showcased “La musica” (Music, 1911), which sought to artistically represent the synesthetic link between color and music—a key theme in Leadbeater’s “Thought-Forms.” Russolo’s work influenced Boccioni’s “La città che sale” (The Rising City, 1910–11).

Besides Milan, Florence was also a major cultural center in Italy during the early twentieth century, with several avant-garde literary journals associated with Theosophy. A key institution was the Philosophical Lending Library (Biblioteca Filosofica), founded in 1905 by Arturo Reghini (1878–1946), a prominent figure in Italy’s esoteric circles. An advertisement from 1906 claimed it had thousands of books for borrowing or reading on topics like “philosophy, psychology, Theosophy, mysticism, religious history, psychical sciences, magic, occultism, Christian Science, and New Thought.” The Library also hosted lectures. Reghini, who founded Florence’s lodge of the Theosophical Society but later distanced himself from Theosophy, lectured about Madame Blavatsky there on March 4, 1906.

In Florence’s circles, Futurism met allies and opponents, with some initially adversaries later becoming friends. Among these was the well-known painter Ardengo Soffici (1879–1964). On July 1, 1914, Soffici authored “Raggio” (Ray) in the Florence magazine “Lacerba,” examining how Theosophical monism influenced the arts. Interestingly, in October 1914, the independent Theosophical journal “Ultra” reprinted this article, titled “La teosofia nel futurismo” (Theosophy within Futurism).

Another focal point of Futurist interest in Italy was Emilia-Romagna. In Ravenna, brothers Arnaldo (1890–1982) and Bruno Ginanni Corradini (1892–1976) came from a noble family with roots in Masonic and anti-clerical traditions. Their parents named them after heretics Arnaldo da Brescia (1090–1155) and Giordano Bruno (1548–1600), as a form of defiance against the Catholic Church. Later, Balla nicknamed Arnaldo “Ginna,” derived from “ginnastica” (gymnastics), and Bruno “Corra,” from “correre” (to run). Both brothers shared an interest in fitness and adopted these names: “Arnaldo Ginna” and “Bruno Corra.”

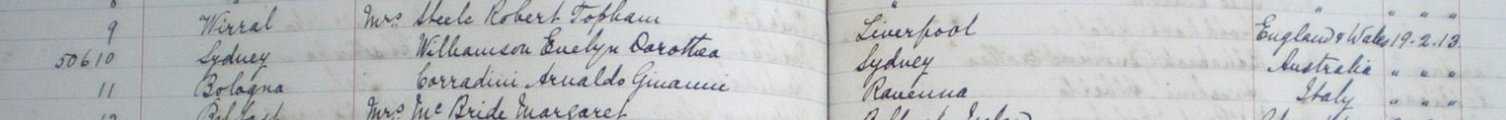

According to Ginna’s memories, they were early “enthusiasts of occult works from Paris publishers Durville and Chacornac and the Theosophical writings of Blavatsky, Besant, Leadbeater, and Schuré.” They attended Theosophical lodge meetings in Florence and Bologna, where they also explored Spiritualist séances and experimented with hashish. In 1908, when Ginna was 18, he and his brother wrote three booklets on harnessing occult energies—“Vita Nova,” “Metodo,” and “Arte dell’avvenire”—and delved into painting by translating feelings and music into colors, likely influenced by Leadbeater. Ginna officially joined the Adyar Theosophical Society on February 19, 1913.

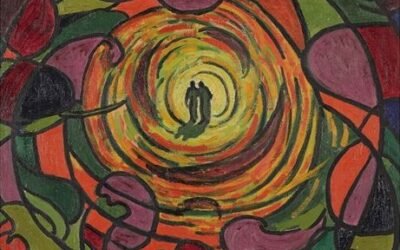

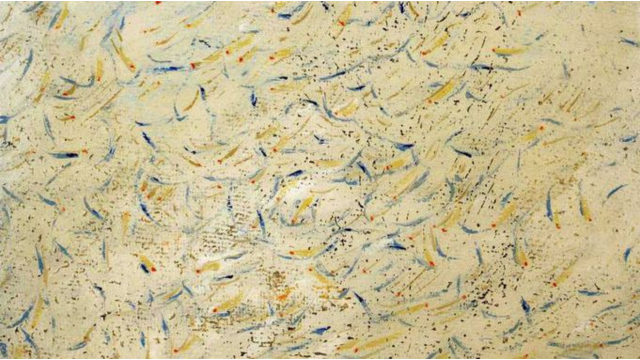

In 1908, Ginna created “Nevrastenia” (Neurasthenia), one of Europe’s earliest abstract artworks. Not only did “Nevrastenia” precede Wassily Kandinsky’s (1866–1944) first abstract watercolor of 1910, but “Arte dell’avvenire” also foreshadowed several ideas from Kandinsky’s 1912 essay “Über das Geistige in der Kunst” (Concerning the Spiritual in Art), which contained Theosophical references. Kandinsky’s art and theories were more advanced and refined; there is no indication he was aware of Ginna. Both artists, however, read similar Theosophical literature.

Kandinsky’s “Concerning the Spiritual in Art” was translated into Italian only twenty years later by Giovanni Antonio Colonna, Duke of Cesarò (1878–1940), a former cabinet minister in Benito Mussolini’s (1883–1945) first government. Cesarò later became an antifascist and a leading figure in Italian Anthroposophy, corresponding with Kandinsky in 1934. In 1936, they spent a holiday together at Forte dei Marmi in Tuscany, discussing art and Anthroposophy. Because of political circumstances, Cesarò’s translation of Kandinsky’s booklet was only published in 1940, although some Futurists read it in German shortly after its original release.

While Kandinsky was unaware of Ginna’s early work, Boccioni and other Futurists certainly knew about it. Boccioni read “Arte dell’avvenire” while preparing for his Rome lecture on May 29, 1911. Ginna, who wasn’t acquainted with Boccioni then, attended the lecture and responded enthusiastically. Subsequently, Ginna and Corra contacted Boccioni and Marinetti through a mutual friend, the Futurist composer Francesco Balilla Pratella (1880–1955), a key figure in Futurist music alongside Russolo. Pratella’s home in Lugo, near Ginna’s hometown of Ravenna, became a hub for artists interested in Theosophy, not all of whom were Futurists.

Among the non-Futurists was painter Filippo de Pisis (born Filippo Tibertelli, 1896–1956), who was associated with the metaphysical school. De Pisis joined the Theosophical lodge in Rapallo in 1916 and, with his sister Ernesta Tibertelli (1895–1973), a fellow Theosophist, published the 1919 Theosophical book “Il verbo di Bodhisattva” (“The Teaching of the Bodhisattva”) under the pseudonym “Maurice Barthelou.” Ernesta was a clairvoyant and may have convinced Filippo that he was the destined Bodhisattva to lead Theosophists into a new era.

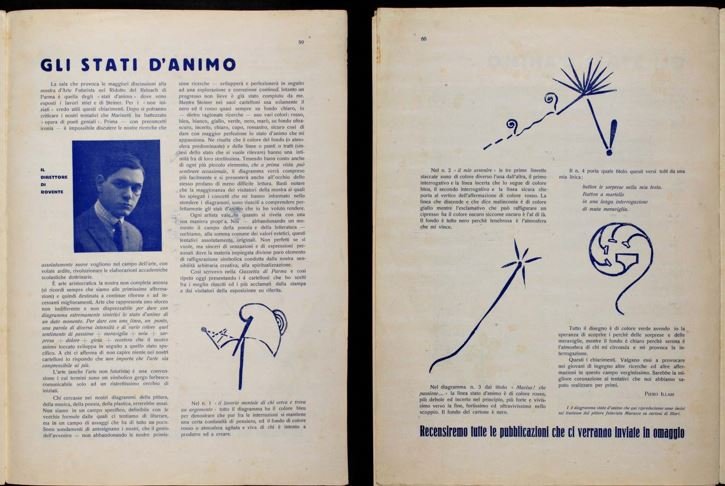

In 1911, Ginna and Corra met Boccioni, Russolo, Carrà, and Marinetti in Milan. The brothers from Ravenna fueled the early Futurists’ interest in Theosophy. They also played a key role in Florence, where they joined the “Blue Patrol,” a Futurist group focused on spiritual and esoteric topics, ultimately helping to establish the journal “L’Italia futurista” in 1916. Their influence extended to Emilia Romagna, primarily through two Futurists who later moved abroad: Piero Illari (1900–1977), who was the secretary of Parma’s Communist Party, and Athos Casarini (1883–1917), based in Bologna. Both shared an interest in Theosophy. Casarini introduced Italian Futurism to New York but returned to fight in World War I, where he was killed. Illari examined the links between feelings and forms through “Thought-Forms” in his Futurist magazine “Rovente,” which featured Balla. Later, he escaped Fascism and moved to Argentina, where he became involved with a circle of painters associated with writer Jorge Luis Borges (1899–1986).

Xul Solar (Oscar Schulz Solari, 1887–1963) was an Argentinian esoteric painter who was part of the same circle and, along with Illari, organized Marinetti’s visit to Buenos Aires in 1926. Solar, whose father was Latvian and his mother from Zoagli on the Italian Riviera, spent time in Italy from 1912 to 1924, though not continuously. His letters show his interest in Theosophy and Anthroposophy and his interactions with Florence’s Futurist circles. These experiences occurred before his significant meeting in 1924 with Aleister Crowley (1875–1947), who introduced him to a different form of esotericism.

In 1915, Ginna wrote “Pittura dell’avvenire” (Painting of the Future), explicitly acknowledging Theosophy as part of the Futurists’ artistic realm: “Anyone who reads Leadbeater’s books ‘Man Visible and Invisible’ and ‘Thought-Forms’ cannot ignore the resemblance between a mystic’s portrayal of the soul’s moods and that of a modern painter.” Eventually, Giacomo Balla became the primary influence on Ginna and Corra.

Massimo Introvigne (born June 14, 1955 in Rome) is an Italian sociologist of religions. He is the founder and managing director of the Center for Studies on New Religions (CESNUR), an international network of scholars who study new religious movements. Introvigne is the author of some 70 books and more than 100 articles in the field of sociology of religion. He was the main author of the Enciclopedia delle religioni in Italia (Encyclopedia of Religions in Italy). He is a member of the editorial board for the Interdisciplinary Journal of Research on Religion and of the executive board of University of California Press’ Nova Religio. From January 5 to December 31, 2011, he has served as the “Representative on combating racism, xenophobia and discrimination, with a special focus on discrimination against Christians and members of other religions” of the Organization for Security and Co-operation in Europe (OSCE). From 2012 to 2015 he served as chairperson of the Observatory of Religious Liberty, instituted by the Italian Ministry of Foreign Affairs in order to monitor problems of religious liberty on a worldwide scale.