A “prophet,” whose revelations come from hallucinogenic plants, believes CESNUR funds AROPL as part of a Jewish “Sabbatian-Frankist” conspiracy.

by Rosita Šorytė

Article 4 of 5. Read article 1, article 2, and article 3.

Scholars who publish work about AROPL often receive emails from a man named Wahid Azal. Some recipients have reported these messages to the police due to their potential implications of violence. Azal is also known for his extensive writings criticizing AROPL, the Baháʼís, and other groups he labels as “cults.”

There is some cause for concern. Azal once posted, answering one of his critics: “I don’t just live in a spider’s house. I am the Spider itself that draws in its prey into its web for the kill! Taking down people like you and your master is what I do for a living. Now, I will also find out the names of your Bahai [sic] contacts one by one and disclose this information directly to Iranian authorities.” Considering that members of the Baháʼí faith are regularly tortured and sometimes killed in Iranian jails, the threat should be taken seriously.

Born in Iran and now residing in Australia, he founded a new religious movement called the Order Sufi Fatimiya. He claims this movement is part of Sufism; however, many Sufis would not recognize it as such. Australian scholar Milad Milani describes it as a “form of New Age syncretic esotericism with unknown membership,” initially founded in 2002 and established in 2005 in Australia (“Sufism in Oceania (Australia and New Zealand),” in “Sufism in Western Contexts,” edited by Marcia K. Hermansen and Saeed Zarrabi-Zadeh, Leiden: Brill, 2023, pp. 378–93 [389]).

Azal’s order signifies a profound transformation in Islamic esotericism, utilizing a variation of the hallucinogenic tea called ayahuasca. Azal also contends that Fatima (605?–632), the daughter of the Prophet Muhammad (570–632), is not just a respected historical figure but a divine incarnation.

Azal, like Scofield, gathers insights from mystical visions and revelations, often induced by hallucinogenic substances. Instead of using the Amazonian ayahuasca (scientific name: Banisteriopsis caapi), he has opted for Syrian rue (Peganum harmala). This change was supposedly mandated during a visionary ayahuasca session with the Mother, the spirit intelligence of ayahuasca, who appears to Azal as Simorgh, the mythical griffin from Persian mythology, and Fatima in a radiant form. He asserts that as a young man, he visited the Kaaba, where Fatima pierced his tongue with Zulfiqar, the mythical sword of her husband Ali (600–661)—an act that symbolizes divine empowerment. Additionally, Azal claims to receive revelations from plants, some of which he believes are manifestations of archangels.

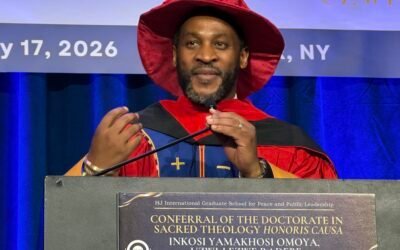

Azal asserts that he is the leader of the global “organizational umbrella” (Milani, op. cit., p. 390) for the original movement founded by the Iranian prophet known as the Báb (1819–1850). He argues that this movement was corrupted and distorted when it evolved into the Baháʼí faith, which he characterizes as the archetypal “cult” (Azal, “The Goal of the Unwise [ghāyat’ul-ḥumq]. Wake Up! Part 2,” Eastern Coast [Brisbane], Australia: Library of the Greatest Name, p. 97; all references to page numbers in this article without other attributions are to this book). His revelations have called him to combat such “cults.” Azal claims a spiritual lineage to the Babi revolutionary and mystic poet Táhirih (1817–1852), identifying her as his direct ancestor and a manifestation of Fatima.

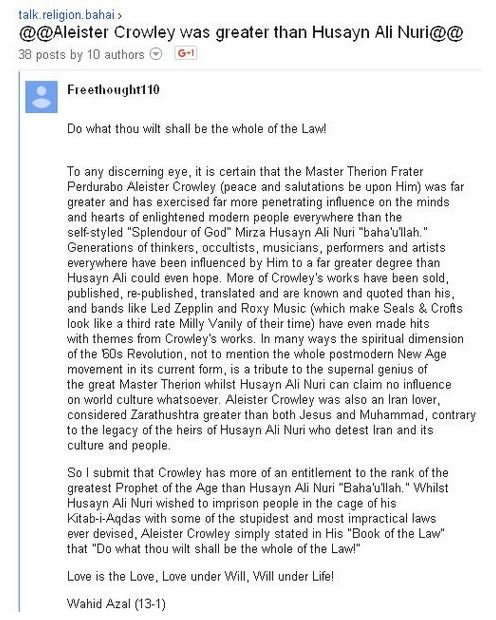

Azal admires both occult master Aleister Crowley (1875–1947), whom he once called a “supernal genius” and “the greatest Prophet of the Age,” and right-wing esoteric author Julius Evola (1898–1974), from whom he derived that the notorious anti-Semitic hoax “The Protocols of the Elders of Zion,” even if materially forged, is reliable in its content and documents the “occult war” of Jews against all non-Jews.

Azal asserts that his mystical experiences have allowed him to move beyond the Marxist ideology he embraced in his youth. Yet, he still considers some elements of it to be valid. His political views are somewhat muddled, but he offers an esoteric interpretation of recent history, highlighting the significance of the Jewish Messianic movements led by Sabbatai Zevi (1626–1676) and Jakob Frank (1726–1791). Both figures claimed to be the awaited Messiah, with Frank presenting himself as Zevi’s reincarnation. Ultimately, their movements collapsed: Zevi’s devotees dispersed after he converted to Islam, while Frank and his followers were baptized en masse as Catholics.

However, Azal believes that what he refers to as the “Sabbatian-Frankist cult” did not vanish but was instead secretly integrated into the Catholic Church as a covert Jewish elite army tasked with special operations against the enemies of the Vatican. During the Cold War and beyond, he claims that the Vatican shared knowledge of these hidden cultists with the American CIA, as the “Sabbatian-Frankist” Jewish-Catholic agents were engaged in covert operations against Marxism and Islam (p. 15).

In recent years, the Catholic Church and the CIA have established what is referred to as a “Sabbatian-Frankist global outreach front” through the efforts of three sinister individuals: Massimo Introvigne, Jean-François Mayer—whom Azal describes as “a controversial Swiss Catholic and historian” (although he is a member of a branch of the Russian Orthodox Church)—, and J. Gordon Melton, a “Methodist minister” whose connections to the Vatican and the CIA are suggested but not elaborated upon. The organization they created, CESNUR, is seen as the modern incarnation of the Sabbatian-Frankist agency controlled by the Vatican. Worse, Azal describes it as “the actual face of evil itself” (p. 18).

Some anti-cult activists have accused CESNUR of receiving funds from various “cults.” In contrast, Azal argues that it is CESNUR that, on behalf of the Vatican, has created and funded “cults,” including the AROPL, which he claims was invented to create discord within the Shia community. According to Azal, “They fund the cults” (p. 36).

He elaborates extensively on how AROPL promotes discord and introduces unorthodox ideas within Muslim communities. One example is the concept of reincarnation, which Azal describes as “an incoherent metaphysical fantasy and thus a complete fallacy” (p. 79). The debates surrounding reincarnation are as ancient as religion itself. What is new is Azal’s conspirationist claim that “reincarnation upholds extremely negative political and social implications, and as such, as a belief, it would implicitly cultivate authoritarian and abusive cult frameworks and paradigms” (p. 80).

Rosita Šorytė was born on September 2, 1965 in Lithuania. In 1988, she graduated from the University of Vilnius in French Language and Literature. In 1994, she got her diploma in international relations from the Institut International d’Administration Publique in Paris.

In 1992, Rosita Šorytė joined the Ministry of Foreign Affairs of Lithuania. She has been posted to the Permanent Mission of Lithuania to UNESCO (Paris, 1994-1996), to the Permanent Mission of Lithuania to the Council of Europe (Strasbourg, 1996-1998), and was Minister Counselor at the Permanent Mission of Lithuania to the United Nations in 2014-2017, where she had already worked in 2003-2006. In 2011, she worked as the representative of the Lithuanian Chairmanship of the OSCE (Organization for Security and Cooperation in Europe) at the Office for Democratic Institutions and Human Rights (Warsaw). In 2013, she chaired the European Union Working Group on Humanitarian Aid on behalf of the Lithuanian pro tempore presidency of the European Union. As a diplomat, she specialized in disarmament, humanitarian aid and peacekeeping issues, with a special interest in the Middle East and religious persecution and discrimination in the area. She also served in elections observation missions in Bosnia and Herzegovina, Georgia, Belarus, Burundi, and Senegal.

Her personal interests, outside of international relations and humanitarian aid, include spirituality, world religions, and art. She takes a special interest in refugees escaping their countries due to religious persecution and is co-founder and President of ORLIR, the International Observatory of Religious Liberty of Refugees. She is the author, inter alia, of “Religious Persecution, Refugees, and Right of Asylum,” The Journal of CESNUR, 2(1), 2018, 78–99.

Languages (fluent): Lithuanian, English, French, Russian.