The exhibition “Hilma af Klint: What Stands Behind the Flowers” challenges the idea that botanical works are the flattest (and least Theosophical) part of the artist’s production.

by Massimo Introvigne

In the shadowed hush of the MoMA’s second-floor rooms, the paintings bloom—not as botanical renderings, but as diagrams of energetic worlds. “Hilma af Klint: What Stands Behind the Flowers,” organized by Jodi Hauptman and running through September 27, is a revelatory showcase of af Klint’s vegetal cosmologies: a series of plant studies and luminous compositions that pulse with meaning beyond pigment or petal. For many visitors, the show may seem an exercise in floral abstraction. But for those attuned to the artist’s spiritual vocabulary, it is unmistakably a gallery of the unseen—a séance of form, coded with Theosophy, vibration, and the etheric.

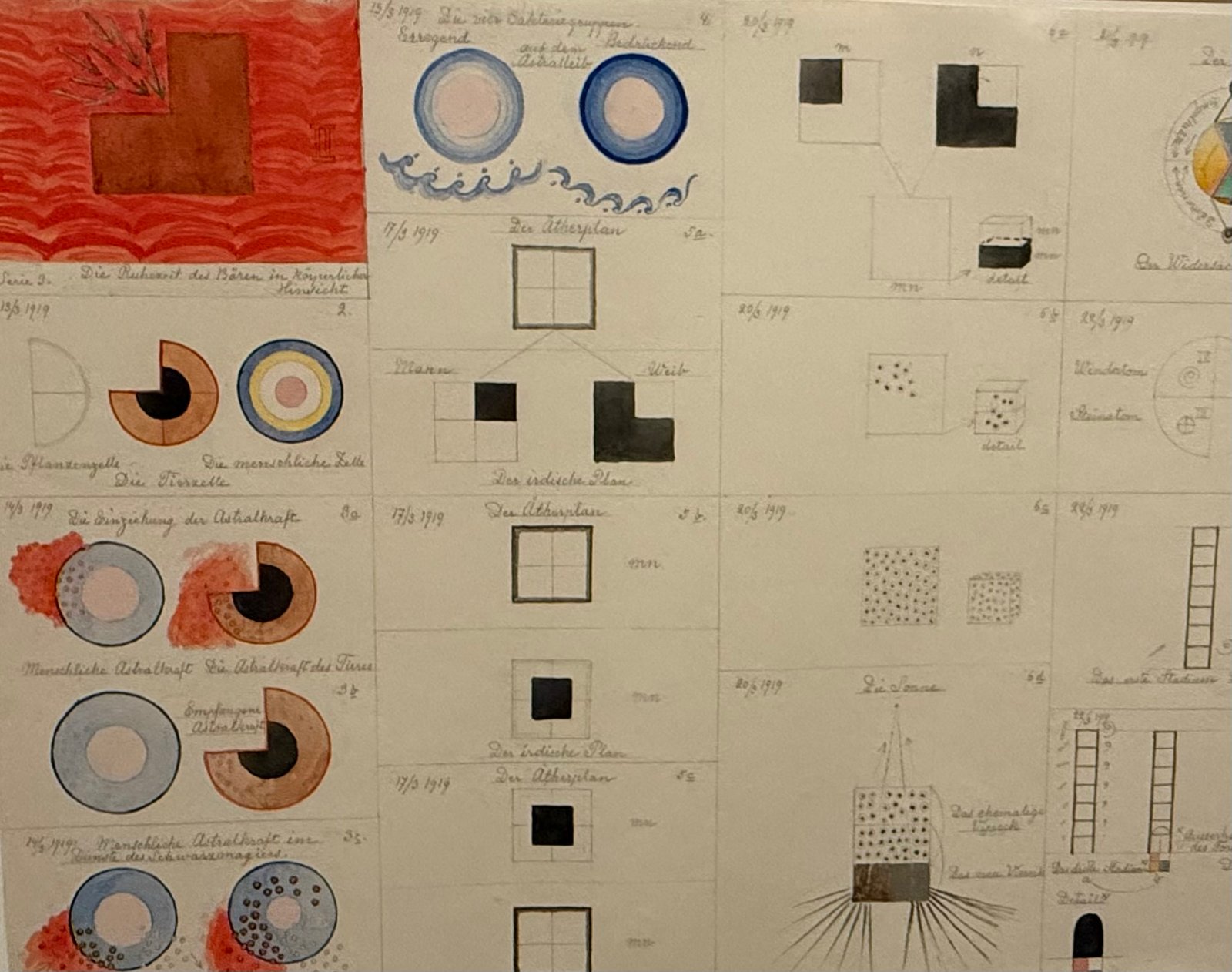

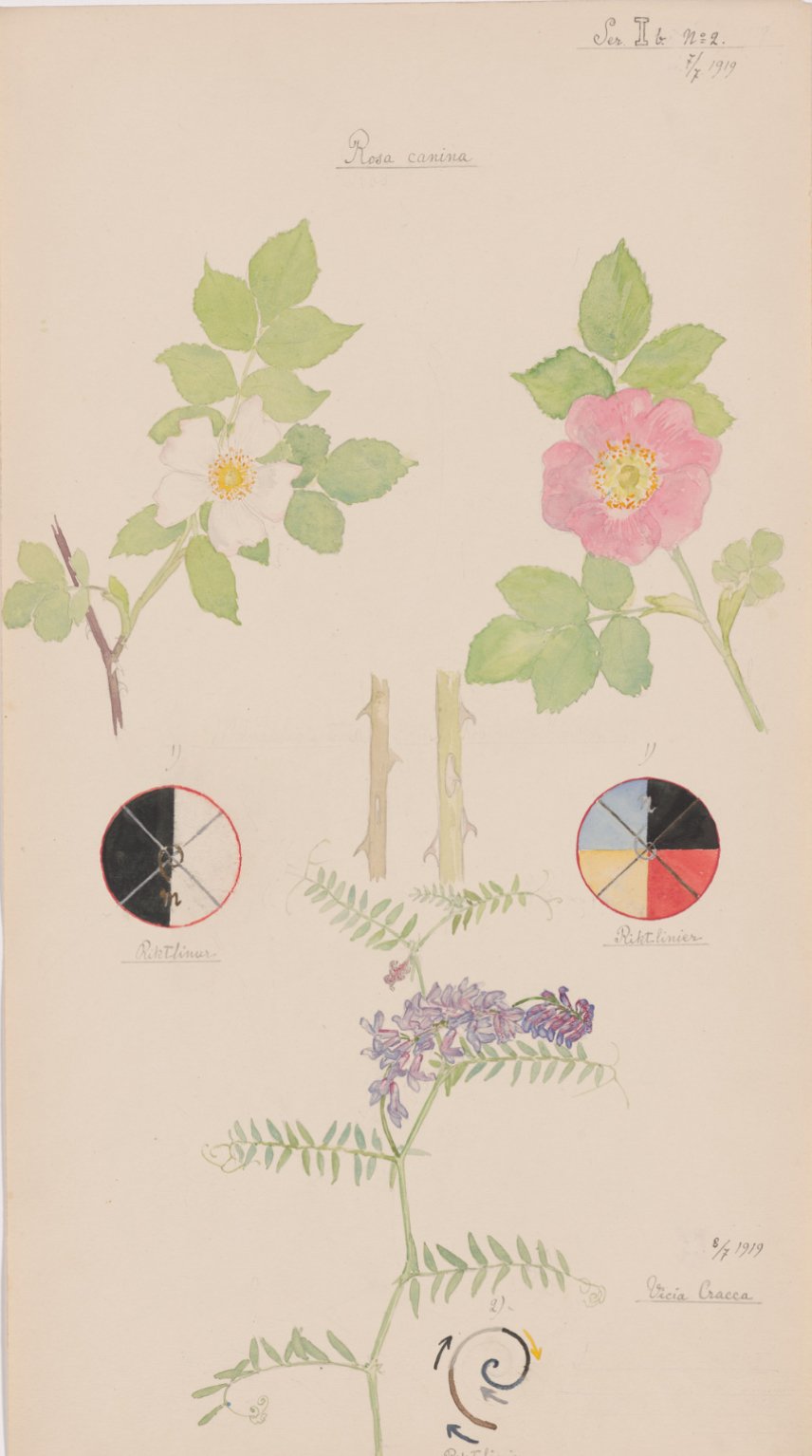

Organized around af Klint’s rarely exhibited botanical works, mostly from 1919 and 1920, the exhibition returns to the question posed in its title: what stands behind the flowers? Not simply a nod to natural science, the phrase evokes af Klint’s entire metaphysical program—her belief, derived mainly from Theosophical writings, that physical phenomena are merely the tip of a deeper spiritual iceberg. In Occult Chemistry (1908), Annie Besant and Charles Webster Leadbeater proposed a clairvoyant analysis of atoms, unveiling esoteric structures vibrating in astral hues and electric geometries. Af Klint had read such texts. Her drawings of lilies, tree branches, and root systems are layered not only with attention to growth and morphology, but with symbolic resonances: double helixes entwining like energy bodies, leaf clusters echoing the chakras.

The catalogue accompanying the exhibition—edited with scholarly elegance by Jodi Hauptman—offers critical insight into af Klint’s esoteric references. Essays by Hauptman and the other contributors, Ewa Lajer-Burcharth, Laura Neufeld, and Lena Struwe, situate af Klint’s vegetal imagery not as marginal to her abstraction, but as central to her spiritual method. Her study of botany at the Royal Academy of Fine Arts in Stockholm was rigorous, but it remained a conduit for her deeper interest in life’s occult architectures. A compelling essay by Hauptman in the catalogue juxtaposes af Klint’s botanical sketches with diagrams in “Occult Chemistry,” revealing shared visual logic: concentric vibrations, tripartite flows, radiant nuclei.

In series like “On the Viewing of Flowers and Trees,”af Klint dissolves the boundary between science and mediumship. Curved roots become spirals of incarnation; plant stems resemble subtle energy channels—the nadis of yogic tradition. These are not didactic illustrations of Theosophy, but artistic equivalents: forms that crystallize af Klint’s belief in the layering of existence, where color and line mediate between matter and its hidden scaffolds.

The exhibition’s layout enhances this mystical progression. Beginning with early naturalistic drawings, viewers are led through increasingly abstract compositions that thrum with unseen life. Curators have wisely kept wall text spare, allowing the works themselves to act as diagrams of the unseen. One feels less like reading a museum label than listening in on a spiritual lecture—one told not in language but in chromatic logic.

But what is most striking, especially in our scientific age, is af Klint’s radical trust in invisible causality. Her flowers are not merely beautiful; they are vessels. She understood the leaf as a symbol of reception, the root as a metaphor of descent, the blossom as a diagram of spiritual evolution. In this, she echoes Besant and Leadbeater’s contention that chemistry, like consciousness, cannot be mapped without clairvoyance. That af Klint dared to represent this conviction on canvas makes her less a modernist and more a metaphysical cartographer.

Even more arresting is the sense that af Klint was not painting “about” flowers, but painting “with” them. Their logic—spiral, radiance, symmetry—is internalized. Theosophy’s notion of interdimensional resonance is not quoted in her work, it’s embodied. The flower becomes not a motif, but a mnemonic of the universe. A catalogued drawing of a cross-sectioned tulip pulses with layers of yellow and blue: hues representing, in af Klint’s color system, spiritual will and divine love. A vine unfurls in a composition, not along a trellis, but across the astral plane. Roses are roses are roses, but af Klint annotates that the dog rose and the glaucous dog rose represent “humanity’s sense of belonging,” while the bird vetch (depicted in the same sketch) is connected with the “spiritual initiative that uplifts the organs of our soul and body.”

For those who still view af Klint through the lens of modernist abstraction alone, this exhibition challenges such framing. Her engagement with the Theosophical Society and, later, Anthroposophy complicates narratives of artistic innovation. This is not the abstraction of reduction, but of revelation. Af Klint’s works are not objects—they are epistemologies. They ask us to see differently. Her flowers do not gesture toward nature; they chant it.

In recent years, af Klint’s work has entered the canon with unprecedented velocity, thanks partly to the Guggenheim’s 2019 blockbuster exhibition. But “What Stands Behind the Flowers” achieves something different and spiritually resonant. By spotlighting her plant-based works, the MoMA show reframes af Klint not only as a visionary painter, but as a psychonaut of form—one whose brush charted energies discussed in Theosophy and seen, perhaps, behind closed eyes.

In a world increasingly skeptical of metaphysical thought, af Klint’s work whispers across centuries. She insists that behind the flower is vibration. Behind the leaf, intention. Behind the pigment, the spirit. And that these things—ephemeral, invisible, inaudible—are the most real of all.

Massimo Introvigne (born June 14, 1955 in Rome) is an Italian sociologist of religions. He is the founder and managing director of the Center for Studies on New Religions (CESNUR), an international network of scholars who study new religious movements. Introvigne is the author of some 70 books and more than 100 articles in the field of sociology of religion. He was the main author of the Enciclopedia delle religioni in Italia (Encyclopedia of Religions in Italy). He is a member of the editorial board for the Interdisciplinary Journal of Research on Religion and of the executive board of University of California Press’ Nova Religio. From January 5 to December 31, 2011, he has served as the “Representative on combating racism, xenophobia and discrimination, with a special focus on discrimination against Christians and members of other religions” of the Organization for Security and Co-operation in Europe (OSCE). From 2012 to 2015 he served as chairperson of the Observatory of Religious Liberty, instituted by the Italian Ministry of Foreign Affairs in order to monitor problems of religious liberty on a worldwide scale.