A book tries to answer a question that has haunted experts for several years: the attack was irrational. Why did China do it?

by Massimo Introvigne

“Why China Intruded Along the Disputed Border with India in May 2020?” edited by Raj Verma (London and New York: Routledge, 2024) tries to answer the difficult question that gives the text its title.

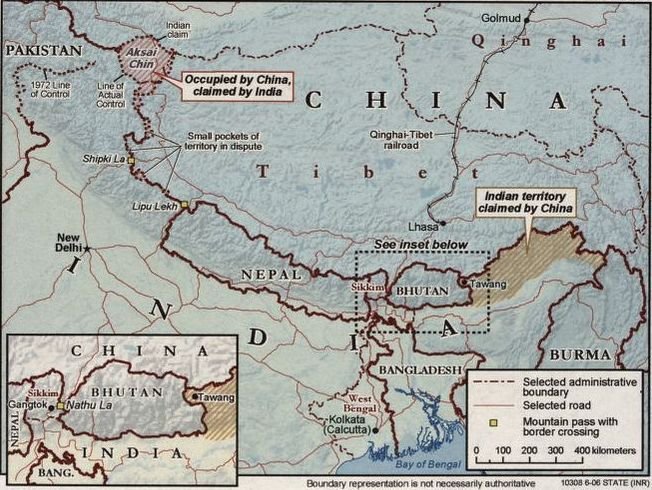

The 2020 clashes between China and India along the border Line of Actual Control (LAC) remain one of the most perplexing geopolitical episodes of recent years. At the height of the COVID-19 crisis—when Beijing was struggling with domestic upheaval and unprecedented international criticism—the People’s Liberation Army suddenly pushed across multiple points of the disputed border, occupying positions from the northern bank of Pangong Tso to the Depsang Plains. The deadly hand-to-hand fighting in the Galwan Valley on June 15–16 shattered decades of carefully maintained protocols and plunged the relationship between the two nuclear-armed neighbors into its worst crisis since 1962.

Why did China do it? The territorial gains were marginal. The diplomatic fallout was immense. For many analysts, the move made little rational sense.

Raj Verma’s edited volume does not pretend to offer a single, neat answer. Instead, it assembles a set of sharply different interpretations—sometimes complementary, sometimes contradictory—that together illuminate the complexity of Beijing’s decision-making. The result is a book that is both intellectually stimulating and, at times, a reminder of how opaque China’s strategic calculus can be.

The opening chapter, by Prashant Kumar Singh, performs a valuable service by clearing away one of the most persistent myths in Indian media: Mao’s supposed “Five Fingers of Tibet” strategy. Singh claims that this revanchist doctrine—according to which China seeks to absorb Nepal, Sikkim, Bhutan, Arunachal Pradesh, and Ladakh, based on old claims by Tibet—has no basis in Maoist writings or in Chinese policy. It is a seductive narrative, but a false one, and Singh argues that clinging to it obscures rather than clarifies Beijing’s behavior.

Other contributors offer more traditional geopolitical explanations. Rishika Chauhan frames the 2020 incursions as part of China’s long-standing “salami slicing” strategy: incremental, deniable land grabs that slowly shift the status quo without triggering full-scale war. This tactic has been used against India for decades, she notes, and also in the South China Sea. From this perspective, 2020 was simply one of the salami’s slices.

Avinash Godbole takes a different angle, arguing that COVID-19 itself pushed Beijing toward risk-taking. Under intense international criticism and worried about its global standing, China sought to demonstrate strength, not weakness. The LAC became a stage on which Beijing could signal—to India, to the IndoPacific, and to its own domestic audience—that the pandemic had not diminished its resolve.

Verma’s own chapter blends two factors: India’s rapid improvement of border infrastructure, especially the Darbuk–Shyok–DBO road, and Home Minister Amit Shah’s 2019 statement asserting India’s claim over Aksai Chin. Neither factor alone explains the timing, Verma argues, but together they fed Beijing’s anxieties about India’s growing assertiveness under the Modi government.

Mahesh Shankar brings in rationalist theory, pointing to the yawning gap in material capabilities between the two countries. China’s economic and military rise has given it more options—and more confidence—along the border. From this vantage point, Beijing might have assumed (incorrectly) that India would back down.

Dalbir Ahlawat returns to history, suggesting that 2020 was a reprise of 1962: a positional strike meant to remind India who leads Asia. As India’s global profile has grown, China may have felt compelled to reassert its primacy.

Harsh Pant and Vivek Mishra add yet another layer: the accelerating India–US partnership. From Beijing’s perspective, the tightening embrace between New Delhi and Washington—especially after the Doklam standoff—looks like containment. The 2020 incursions, they argue, were a warning shot: do not come too close to the United States, or else.

The final chapters shift from diagnosis to prescription. Sidharth Raimedhi argues that India’s deterrence posture has eroded and must be rebuilt through greater military investment, a stronger domestic defense industry, and a renewed emphasis on “denial” rather than “punishment.” The epilogue paints a sobering picture of the future: a border more militarized, more brittle, and more prone to escalation than at any time in recent memory.

Taken together, the essays make for a rich, multifaceted volume. At times, the technicalities and theoretical frameworks may feel dense, but the book’s value lies precisely in its refusal to settle for a single explanation. The 2020 crisis was overdetermined—born of history, insecurity, ambition, misperception, and structural power shifts.

Yet one conclusion emerges clearly, even if the contributors state it with varying degrees of caution: China’s incremental encroachments along the LAC are part of a broader pattern of behavior that violates international norms and destabilizes regional security. The same “salami slicing” tactics seen in the Himalayas are visible in the South China Sea, around Taiwan, and in China’s dealings with several of its neighbors. The international community would be unwise to treat the 2020 incursions as an isolated aberration.

What happened in 2020 was a warning. China’s actions along the LAC are not only a bilateral issue between Beijing and New Delhi—they are a symptom of a broader strategic posture that should concern anyone invested in Asia’s stability. For readers of “Bitter Winter,” accustomed to tracking China’s assertiveness in the religious, cultural, and political spheres, this book offers a valuable window into how that assertiveness plays out on the world’s highest battlefield.

Massimo Introvigne (born June 14, 1955 in Rome) is an Italian sociologist of religions. He is the founder and managing director of the Center for Studies on New Religions (CESNUR), an international network of scholars who study new religious movements. Introvigne is the author of some 70 books and more than 100 articles in the field of sociology of religion. He was the main author of the Enciclopedia delle religioni in Italia (Encyclopedia of Religions in Italy). He is a member of the editorial board for the Interdisciplinary Journal of Research on Religion and of the executive board of University of California Press’ Nova Religio. From January 5 to December 31, 2011, he has served as the “Representative on combating racism, xenophobia and discrimination, with a special focus on discrimination against Christians and members of other religions” of the Organization for Security and Co-operation in Europe (OSCE). From 2012 to 2015 he served as chairperson of the Observatory of Religious Liberty, instituted by the Italian Ministry of Foreign Affairs in order to monitor problems of religious liberty on a worldwide scale.