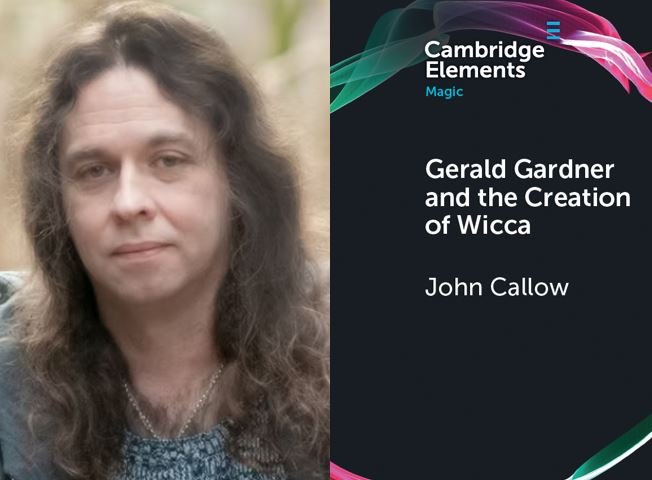

John Callow does not ignore Gardner’s shortcomings but restores his complexity, generosity, and crucial role in the creation of a new global religion.

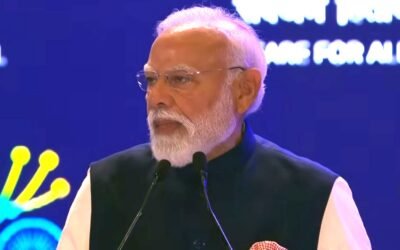

by Massimo Introvigne

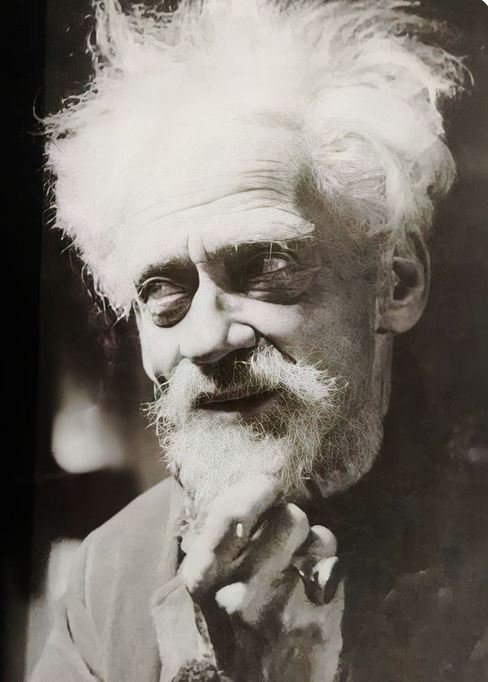

Gerald Gardner (1884–1964), the man who conjured Wicca into existence and then insisted he hadn’t, finally gets the credit he deserves in the University of Suffolk’s John Callow’s “Gerald Gardner and the Creation of Wicca” (Cambridge Elements, 2025). This slim but potent volume reads like a scholarly séance—summoning Gardner’s ghost from the margins of history and giving him back his wand, robes, and reputation.

Callow opens with a paradox: Gardner is universally acknowledged as the father of Wicca, yet his name is often treated as an embarrassment. Why? Three reasons, Callow argues. First, Gardner insisted Wicca was not his invention but the secret survival of a Paleolithic goddess cult. This allowed him to present himself not as a founder but as a humble messenger. The myth was seductive, but it muddied the historical waters. Second, Wicca was crafted as a female-led, goddess-centered religion. A balding British man claiming to have birthed it felt incongruous. Gardner’s solution was to fade into the mythos and let the goddess take center stage. Third, Charles Cardell (1895–1977), Gardner’s personal enemy, launched a “scurrilous” campaign portraying him as a sex-obsessed, egocentric fraud. Unfortunately, this caricature was picked up by journalists, scholars, and even some Wiccans, casting a long shadow over Gardner’s legacy.

Callow reconstructs Gardner’s biography with forensic flair. Born in 1884 into a wealthy family, Gardner was raised by Georgina McCombie (1865–1945), a governess who may have been his biological mother. She was both abusive and affectionate, and took young Gerald on travels across the globe, giving him little formal schooling but a voracious appetite for self-education.

Between 1909 and 1921, Gardner worked as a tea and rubber planter in Ceylon, North Borneo, and Malaya. He joined Freemasonry in Colombo in 1910 and immersed himself in local religions, including Hindu Tantrism and village shamanism. He became an expert in Malay weaponry and published “Keris and Other Malay Weapons” in 1936, which earned praise from scholarly societies and even “The Sunday Times.”

From 1921 to 1936, Gardner served in British customs in Asia, ostensibly fighting the opium trade. Callow suggests Gardner may have taken bribes from traffickers—a theory that explains his sudden wealth and early retirement. In 1937, he acquired a doctorate from a disreputable American diploma mill and tried to pass as a scholar, speaking at international conferences where his papers were accused of plagiarism. Salvation came in the form of Margaret Murray (1863–1963), who befriended Gardner and whose theories about witchcraft as a secret survival of pre-Christian religions (now debunked but taken seriously at that time) inspired Gardner’s self-published novel “A Goddess Arrives” (1939).

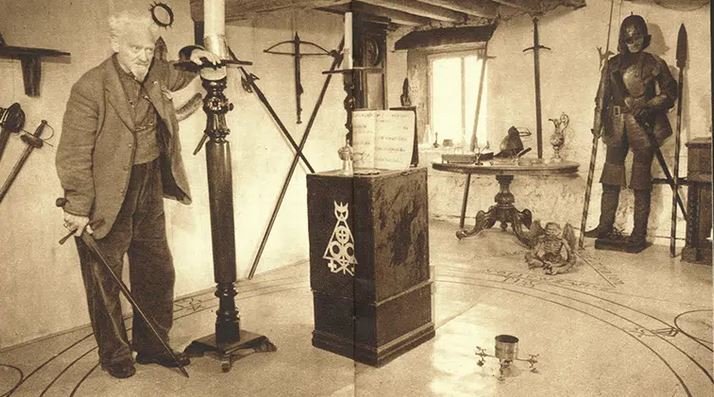

In 1938, Gardner moved to Highcliffe near the New Forest, partly to be near McCombie, who had retired there. The area was a hotbed of esoteric activity, including a Rosicrucian Theatre linked to Co-Masonry and led by Mabel Besant-Scott (1870–1952), daughter of Theosophical and Co-Masonry leader Annie Besant (1847–1933). Gardner joined several groups: the Ordo Templi Orientis (meeting Aleister Crowley, 1875–1947), the Ancient Druid Order, and the Ancient British Church.

It was here that Gardner claimed to be initiated into a secret witchcraft tradition dating back to the Paleolithic. Scholars remain skeptical, although some of Gardner’s followers treat it as gospel. He also claimed his coven performed magical rituals to help Britain defeat the Nazis—a claim Callow calls “risible.” However, he notes Gardner’s sincere hatred of Nazism and right-wing politics, a rare stance among occultists of the time.

In 1949, Gardner published “High Magic’s Aid,” a novel that marked his public emergence as the heir to ancient witchcraft. Unlike his earlier writings, it was successful. Callow identifies six core features of Gardner’s Wicca. It was female-led and goddess-centered. It was pagan, with Christianity ignored or denounced for the witch hunts (Gardner claimed nine million victims, a number not supported by historians). It emphasized ritual nudity. It believed in reincarnation. It used magical techniques to induce altered states of consciousness. Crucially, there was no mention of the Devil—neither as friend nor foe.

In 1951, Britain repealed its witchcraft laws, dating back to 1736. Gardner seized the moment, promoting himself as both author and practitioner. His 1954 book “Witchcraft Today,” with an introduction by Margaret Murray that added academic credibility, became the foundational text of Wicca. In 1959, he published “The Meaning of Witchcraft” as a follow-up, partly ghostwritten by Doreen Valiente (1922–1999), a talented witch and collaborator.

Among Gardner’s early companions was Edith Woodford-Grimes (1887–1975), his brief lover. Callow emphasizes that she, too, was not the heir of any ancient tradition, despite Gardner’s claims.

In 1951, Gardner moved to the Isle of Man to partner with filmmaker and occultist Cecil Williamson (1909–1999), who owned a Museum of Witchcraft. Gardner became the “resident witch,” and the museum flourished. But tensions arose: Williamson emphasized the dark and Satanic side of witchcraft, believing it would attract tourists, which Gardner had always dismissed as Christian propaganda. They parted ways, with Gardner keeping the museum and a coven.

During this period, Gardner befriended Idries Shah (1924–1996), a flamboyant neo-Sufi author who had also settled in the Isle of Man. He promoted Gardner and introduced him to poet Robert Graves (1895–1985), the author of “The White Goddess.” Graves was more enchanted by Shah than Gardner, but the connection helped Gardner’s reputation.

By the early 1960s, Wicca was gaining traction in America. Gardner was “riding a wave of success” when he died of a stroke on February 12, 1964, aboard a cargo ship off the coast of Tunis during one of his annual winter cruises.

Callow closes by returning to the theme of Gardner’s fading reputation. One reason was his choice of Monique Wilson (1923–1982) as his heir—a divisive figure who alienated much of the Wiccan community. She eventually left Wicca and sold the museum to Ripley’s Believe It or Not. The museum was later closed after Christian protests.

Despite Gardner’s patriarchal tendencies and sometimes abusive treatment of female disciples, Callow insists on his “brilliance and bravura” and “essential generosity of spirit.” Gardner created Wicca, yet denied it, presenting himself as a mere transmitter of an ancient tradition. It was a myth—but a powerful one.

Callow’s book is short, sharp, and scholarly with just enough scandal to keep the cauldron bubbling. He doesn’t quite exonerate Gardner but gives him back his complexity: a man of contradictions, charisma, and creative chaos. Gardner may not have summoned storms or defeated Nazis with spells, but he did conjure a religion that still enchants thousands.

So next time you cast a circle, spare a thought for Gerald Gardner—the wizard of odd who made Wicca happen, even if he had to rewrite history to do it.

Massimo Introvigne (born June 14, 1955 in Rome) is an Italian sociologist of religions. He is the founder and managing director of the Center for Studies on New Religions (CESNUR), an international network of scholars who study new religious movements. Introvigne is the author of some 70 books and more than 100 articles in the field of sociology of religion. He was the main author of the Enciclopedia delle religioni in Italia (Encyclopedia of Religions in Italy). He is a member of the editorial board for the Interdisciplinary Journal of Research on Religion and of the executive board of University of California Press’ Nova Religio. From January 5 to December 31, 2011, he has served as the “Representative on combating racism, xenophobia and discrimination, with a special focus on discrimination against Christians and members of other religions” of the Organization for Security and Co-operation in Europe (OSCE). From 2012 to 2015 he served as chairperson of the Observatory of Religious Liberty, instituted by the Italian Ministry of Foreign Affairs in order to monitor problems of religious liberty on a worldwide scale.