The same investigation by the same Special Prosecutor and team persecuting Mother Han led, not surprisingly, to the suicide of a Yangpyeong County official.

by Massimo Introvigne

South Korea’s democratic institutions are in crisis. The tragic suicide of a Yangpyeong County official—interrogated for hours by Special Prosecutor Min Joong-ki’s team—has exposed the brutal underside of a prosecutorial system that trades justice for psychological torment. This death, the first fatality linked to the Special Prosecutor’s investigation, is not an isolated tragedy. It is a warning. And it casts a long, chilling shadow over the continued detention and interrogation of Mother Han.

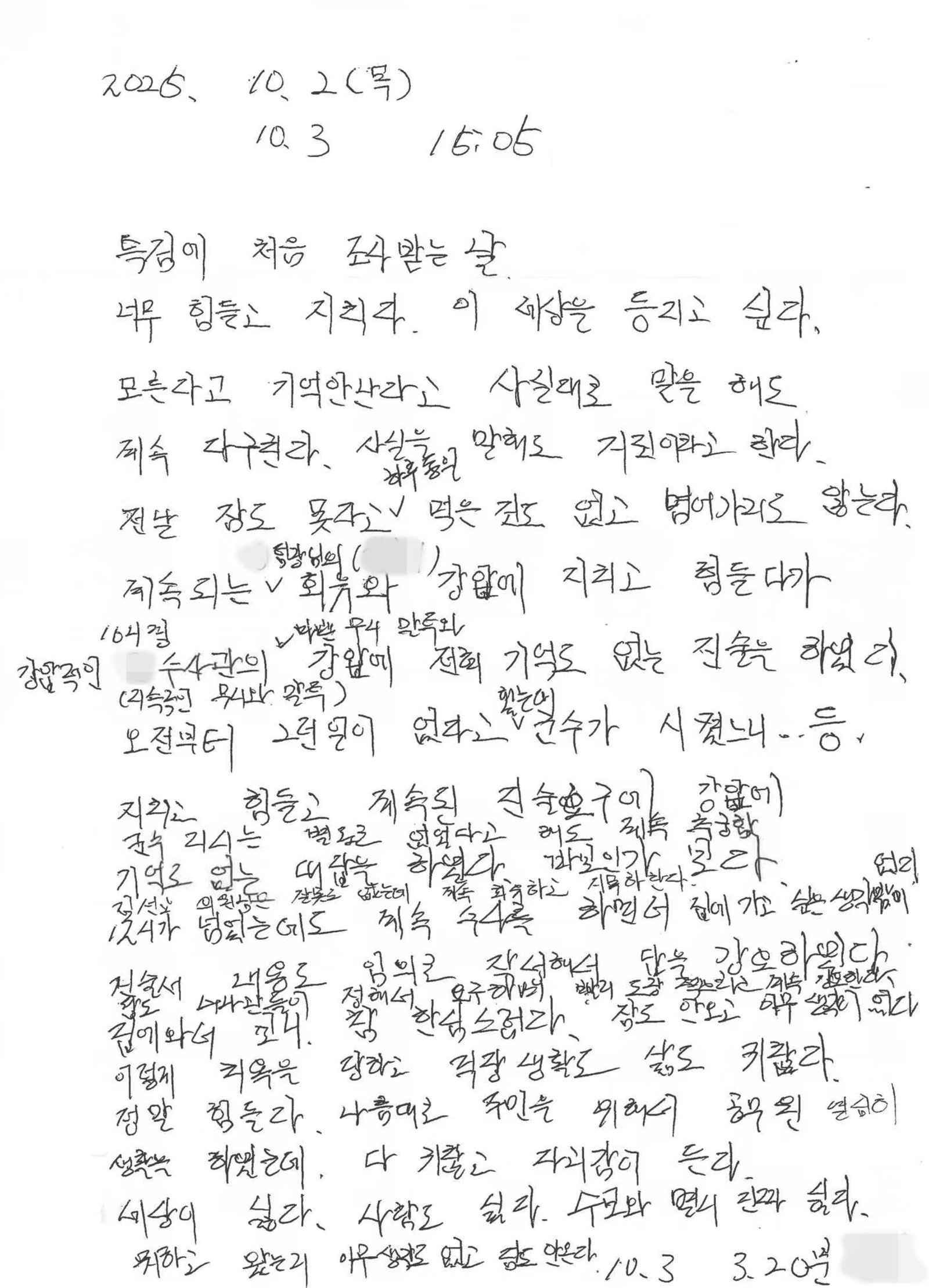

The official, 57-year-old Jeong Hee-cheol, was summoned on October 2 by Min Joong-ki’s team as part of the probe into alleged “special favors” in the Gongheung District development. He was interrogated from 10 a.m. until after midnight, returning home at 1:15 a.m. on October 3. Just two hours later, he penned a handwritten note expressing despair: “I want to turn my back on the world.” On October 10, he was found dead at his home.

The suicide note, reportedly withheld from the bereaved family by police, allegedly contains repeated references to coercion, humiliation, and psychological pressure. According to People Power Party lawmakers who reviewed its contents, words like “coercion,” “disregard,” “humiliation,” and “force” appear eighteen times. The note paints a picture of a man crushed not by guilt, but by a system designed to extract confessions through psychological attrition.

The lawyer representing the deceased official has demanded access to interrogation records and challenged the Special Prosecutor’s claim that “no coercive investigation” took place. “Just because they say they didn’t engage in coercion doesn’t mean they didn’t,” the lawyer stated, adding that the refusal to disclose the suicide note and the push for an autopsy against the family’s wishes only deepen the suspicion.

This is the same prosecutorial team that has subjected Mother Han to prolonged, psychologically grueling interrogations. The same persons. The same investigation. The leader of the Family Federation for World Peace and Unification, Mother Han, has been detained and questioned for hours on end, in conditions that mirror those described in the suicide note. Her treatment is not an exception—it is the rule. And now, with one life lost, the stakes have become intolerably high.

The death of Jeong is not a misstep. It is the logical consequence of a system that weaponizes interrogation. The Special Prosecutor’s office, under Min Joong-ki, has turned questioning and pre-trial detention into psychological warfare. The goal is not truth—it is submission. And the cost is human life.

This tragedy demands accountability. The resignation of Min Joong-ki is not optional—it is imperative. The interrogation records must be released. The suicide note must be made public. And above all, the innocent Mother Han must be freed. Immediately and unconditionally. Every hour she remains in custody is another hour of sanctioned torment. Although Mother Han’s moral and spiritual force is admirable, if the system broke Jeong, it can break others.

South Korea must choose: continue down the path of repression, or reclaim its democratic soul. The world is watching. And silence is complicity.

Massimo Introvigne (born June 14, 1955 in Rome) is an Italian sociologist of religions. He is the founder and managing director of the Center for Studies on New Religions (CESNUR), an international network of scholars who study new religious movements. Introvigne is the author of some 70 books and more than 100 articles in the field of sociology of religion. He was the main author of the Enciclopedia delle religioni in Italia (Encyclopedia of Religions in Italy). He is a member of the editorial board for the Interdisciplinary Journal of Research on Religion and of the executive board of University of California Press’ Nova Religio. From January 5 to December 31, 2011, he has served as the “Representative on combating racism, xenophobia and discrimination, with a special focus on discrimination against Christians and members of other religions” of the Organization for Security and Co-operation in Europe (OSCE). From 2012 to 2015 he served as chairperson of the Observatory of Religious Liberty, instituted by the Italian Ministry of Foreign Affairs in order to monitor problems of religious liberty on a worldwide scale.