China has published a document meant to be reassuring, but that looks more like a threat.

by Gladys Kwok

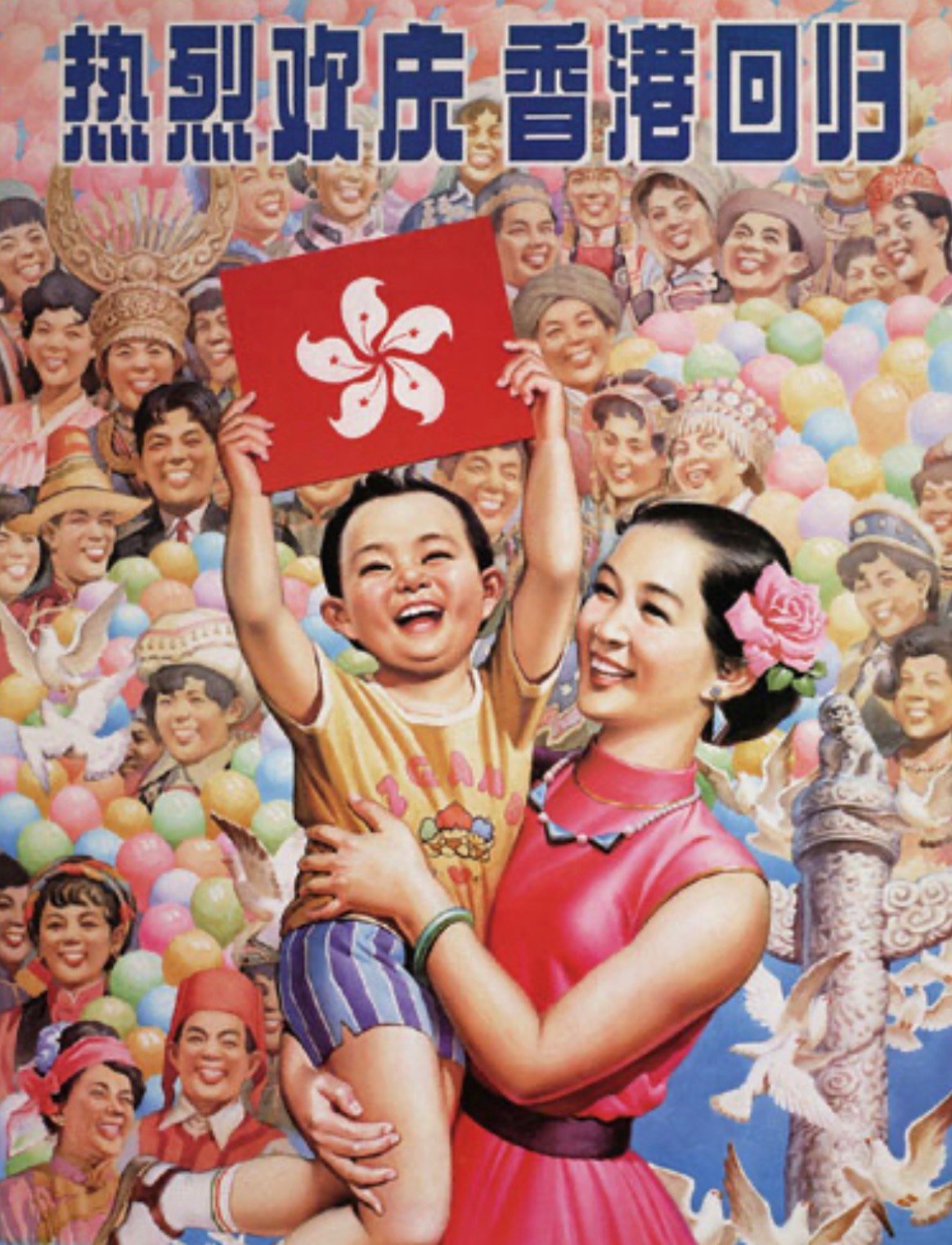

If Beijing’s February 2026 “Hong Kong White Paper” were a film, it would open with triumphant music, sweeping drone shots of Victoria Harbour, and a narrator assuring the audience that everything is finally under control. The title alone—“Hong Kong: Safeguarding China’s National Security Under the Framework of One Country, Two Systems”—stands somewhere between a constitutional treatise and a prestige‑drama miniseries.

The plot, as presented, is straightforward: Hong Kong was once besieged by chaos, but thanks to decisive action from the central government, order has been restored, prosperity is blooming, and the city is now governed exclusively by “staunch patriots,” a phrase repeated so often it begins to feel like a mantra. The White Paper’s narrative is polished, confident, and utterly uninterested in the messy complexities that usually accompany political transformation. It celebrates the National Security Law as a kind of miracle cure, a legal antibiotic that eliminated a “tiny minority” of troublemakers and left the rest of society healthier than ever. The fact that this miracle cure has also produced a climate of fear, self‑censorship, and the quiet disappearance of political pluralism is treated as either irrelevant or imaginary, depending on the paragraph.

The document insists that human rights are “fully respected and protected,” a claim delivered with the serene certainty of someone who assumes no one will check the reality. It also highlights that national security cases make up less than 0.2 percent of all prosecutions, a statistic that sounds reassuring until one remembers that the number of people struck by lightning is also very small. Yet, most of us still avoid standing under trees during a storm. The issue is not the quantity of prosecutions but the breadth of the law itself, which defines “subversion,” “secession,” and “collusion with foreign forces” so expansively that almost any form of dissent can be swept into the net. Critics argue that the law’s vagueness is the point: it is not designed merely to punish but to discourage, to make people think twice before speaking, writing, organizing, or even reposting.

Nowhere is this dynamic more visible than in the case of Jimmy Lai, the media tycoon whose recent sentencing to twenty years in prison is treated in the White Paper with the emotional weight of a footnote. Lai’s prosecution is framed as a triumph of law‑based governance, proof that the system is working exactly as intended. The White Paper drily comments that the Lai case proved that “anti-China agitators who sought to destabilize Hong Kong were convicted and put in jail in accordance with the law.” International observers, meanwhile, see it as a symbol of Hong Kong’s shrinking freedoms, a warning that political dissent—once a defining feature of the city’s identity—has been reclassified as a national security threat. Lai’s imprisonment is not just a legal event; it is a message: the era of noisy, pluralistic politics is over. The White Paper does not dwell on this interpretation. Instead, it pivots quickly to economic achievements, pointing to Hong Kong’s high rankings in international indices, its influx of capital, and its improved social welfare programs. The implication is that prosperity is the ultimate proof of good governance, and that political freedoms are, at best, optional accessories. It is a familiar argument: stability first, rights later—though “later” has a way of stretching indefinitely.

Patriotism, in this new narrative, is a qualification. To govern Hong Kong, one must “love the country,” a requirement that sounds benign until one realizes it functions like a velvet rope outside an exclusive club. Those who pass the test are welcomed into the political establishment; those who do not are quietly escorted out of public life. The White Paper presents this as common sense, a necessary safeguard against instability. Critics see it as a political litmus test designed to eliminate opposition and homogenize public discourse. The city that once prided itself on its diversity of voices now finds itself curated, edited, and streamlined.

International reactions to this transformation have been predictably critical. Western governments issue statements of concern; human rights organizations warn of democratic backsliding; Beijing dismisses these critiques as misunderstandings or, more dramatically, foreign interference. The White Paper positions Hong Kong as a model for the “Chinese path” to security, a phrase that may cause unease in places where national security is not typically used as a catch‑all justification for political restructuring. Yet the document remains unwavering in its confidence. It concludes with the triumphant assertion that order has been restored, prosperity secured, and sovereignty affirmed. What it does not acknowledge is the cost: the silencing of dissent, the erosion of civil society, the imprisonment of figures like Lai, and the quiet transformation of Hong Kong from a city known for its openness to one increasingly defined by caution.

The tension between these two narratives—the official story of stability and the lived reality of shrinking freedoms—hangs over the city like a question that cannot be asked aloud. Can Hong Kong continue to thrive economically while constraining the very openness that once made it exceptional? The White Paper says yes, emphatically. Jimmy Lai’s prison sentence suggests the answer may not be so simple. And somewhere between those two visions lies the real Hong Kong, still vibrant, still resilient, but increasingly forced to navigate a political landscape where the boundaries of acceptable expression are drawn ever more tightly, and where the future depends on how long the city can balance prosperity with the quiet, growing pressure of conformity.

Uses a pseudonym for security reasons.