In the New York exhibition, the Cuban artist returns in full spiritual force, his canvases pulsing with Santería, Vodun, and the whispered knowledge of Lydia Cabrera.

by Massimo Introvigne

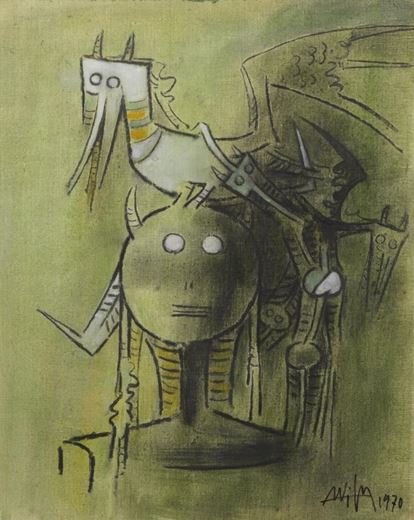

I grew up with Wifredo Lam. Not in a metaphorical sense, but literally: my father, an art collector with a taste for the unusual, owned an “Untitled” Lam that hung in our living room like a gateway to another universe. It was a dense, horned, animal-headed figure—half human, half orisha, half nightmare. I spent several years trying to understand it.

Unfortunately, it has long since been sold for only a fraction of what it would be worth today, which, in retrospect, was both a financial and a spiritual loss. Lam was never just decoration. He was haunting.

Walking into the Museum of Modern Art’s retrospective, which runs through April 2026 and boldly places Lam in the “Olympus of modern art,” felt like attending a family reunion with ancestors. The show is a revelation, not because it uncovers anything new, but because it finally acknowledges what Lam was doing all along: sneaking Afro-Caribbean religion into the heart of Western modernism. For those of us who view art through the lens of religious studies, Lam is a priest, a medium, and a Trojan horse.

The curators have wisely embraced Lam’s spiritual background. Born in Cuba to a Chinese father and an Afro-Cuban mother, Lam grew up immersed in Santería. His godmother, Mantonica Wilson, was a priestess of Shango, the orisha of thunder and war. She gave him an amulet consecrated under Shango’s influence, which he kept for life and served as his theological foundation. Lam’s art is filled with “femme cheval” figures, horse-headed women who reflect the possessed devotee “ridden” by an orisha or loa. In Vodun and Santería, the horse is not just symbolic. It represents a state of being. Lam’s women are not victims of possession; they are vessels of power.

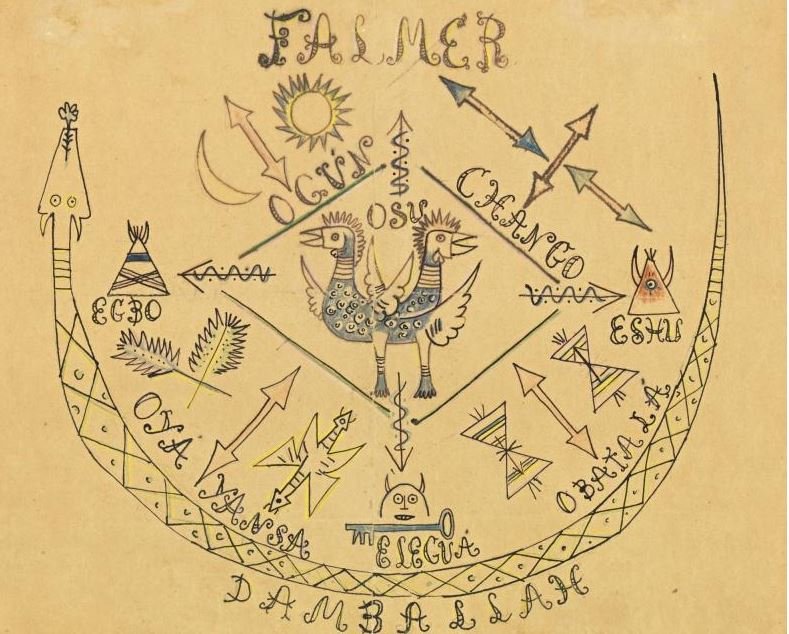

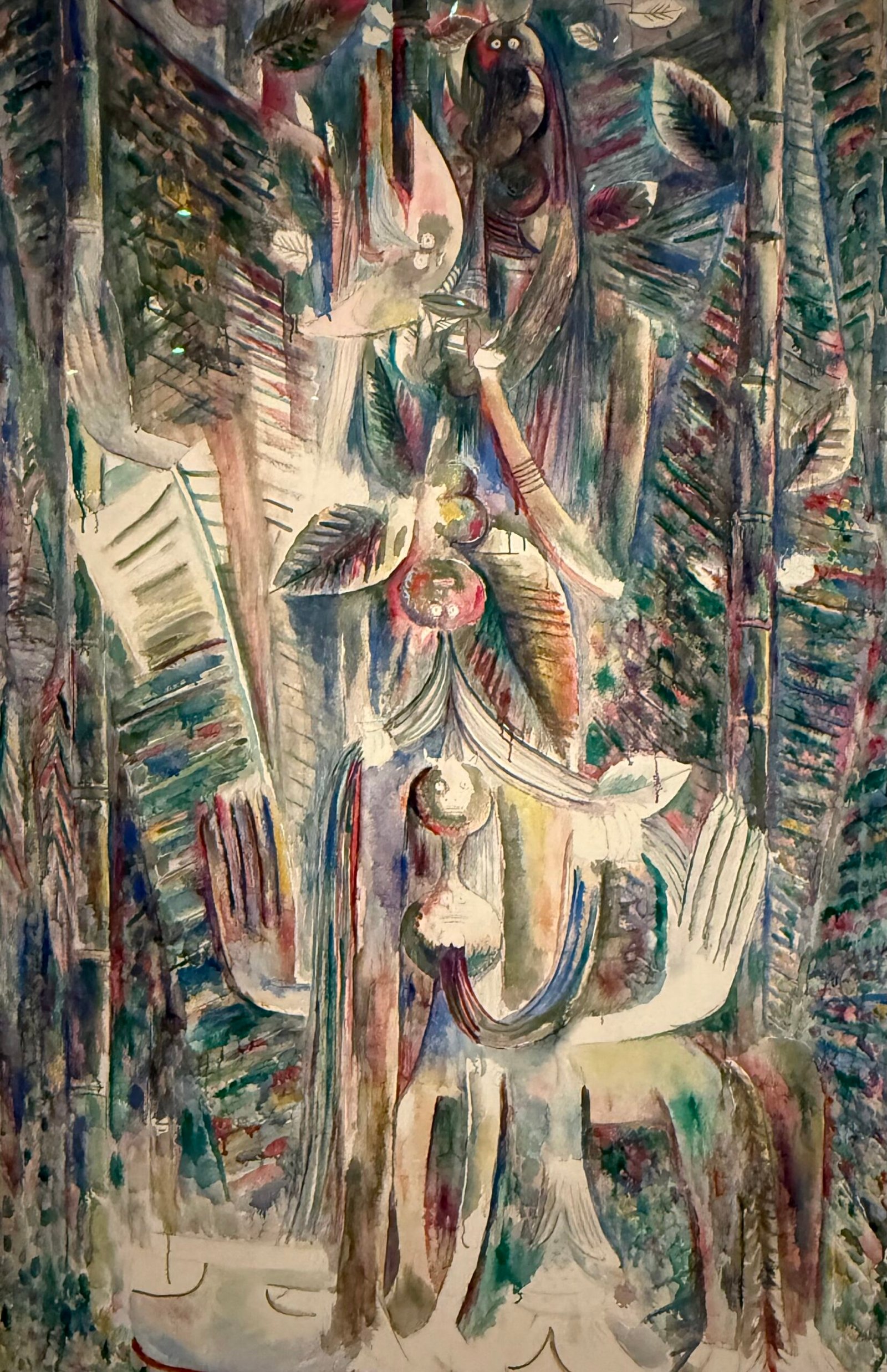

One of the most striking works in the exhibition is his 1946 drawing “Untitled (Yoruba Pantheon),” which serves as a cosmographic guide. Obatalá, Oshun, Oya, Eleguá—they’re all present, depicted not as icons but as beings. Lam’s bulbous-eyed figures, with their swelling spiritual vision (“oju inún”), do not look at us but through us. They are perceiving something that we cannot see. Then there’s the botany: Anamu, the herb “owned” by the orishas, appears in his artwork like a signature and a warning.

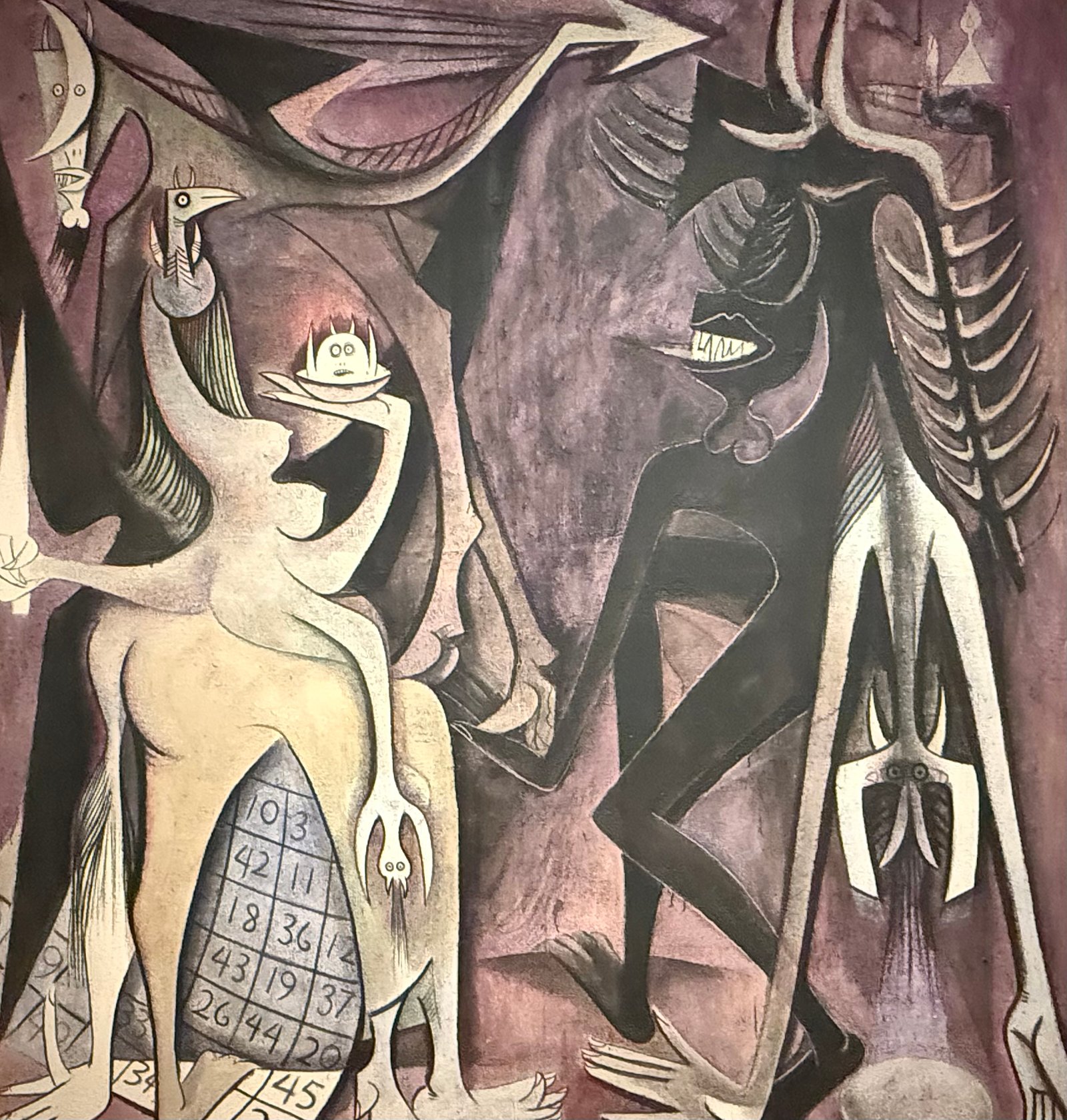

Another impressive piece is “Belial, empereur des mouches” (1948). In this work, Lam brings the demonic figure Belial to life. This figure originates in Christian mythology and has been incorporated into Vodou beliefs.

The painting features a dark violet background that evokes Baron Samedi and Maman Brigitte, the deities of the dead. It is a place for ritual, where the flies are not nuisances but rather witnesses.

Lam’ wellknown masterpiece, “The Jungle” (1943), also hangs nearby like a manifesto in paint—an emblem of MoMA’s collection that fuses Surrealism, Cubism, and AfroCuban spirituality into a dense thicket of hybrid humananimal beings pressed against sugarcane, a visual indictment of colonial history and a reminder that identity, justice, and the sacred are never separate in Lam’s world.

Lam’s monumental “Grande Composition “(1949)—a vast oilandcharcoal mural where maskfaces and hybrid spirits rise from ocher and kraftpaper browns—unfurls like a liberation myth, its meticulous lines merging Surrealism with Santería to imagine a spiritual rebirth for Cuba after colonial trauma, and its sheer scale reminding viewers why MoMA treats it as one of his defining, worldmaking works.

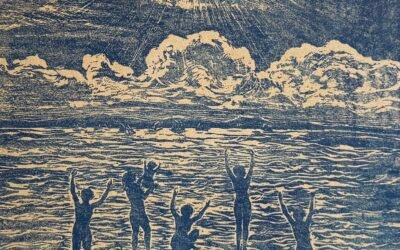

Lam’s religious palette expanded during his time in Haiti (1945–46), where he immersed himself in Vodun practices and studied the flour-drawn vévés used to summon loas. His painting “Les Abaloches dansent pour Dhambala” (1970) is a nighttime hymn to Damballah, the serpent-spirit of unity. Lam believed the African gods survived the Middle Passage and continued to work to heal the scars of slavery. His “négritude” was not a form of resistance. He was painting defiance rather than folklore.

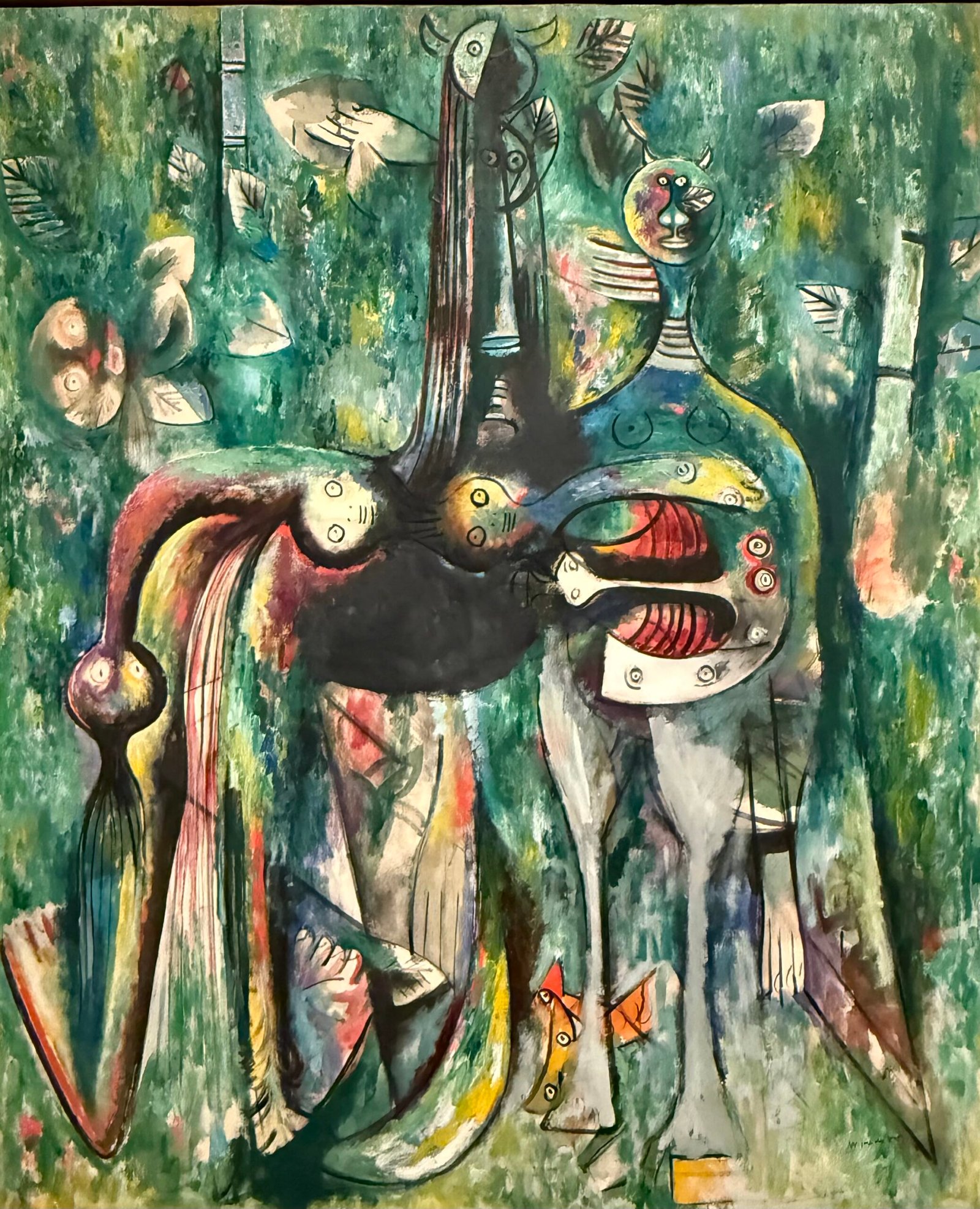

Lam’s “Le sombre Malembo, Dieu du carrefour” (1943) adds yet another layer to this spiritual cartography: a luminous, unsettling vision in which the central figure—widely read as Eleguá, the orisha of the crossroads—emerges from a vibrating field of green. It is one of Lam’s clearest fusions of Cubist fracture, Surrealist dream-logic, and Afro-Cuban theology, a painting where the god who opens paths seems to slice through the canvas itself. The work’s charged atmosphere speaks to Lam’s lifelong preoccupation with injustice, identity, and the metaphysical survival strategies of the African diaspora; in this piece, the crossroads is not merely a symbol but a spiritual condition, a place where fate, history, and the sacred negotiate their terms.

The exhibition insists on Lam’s relationship with Lydia Cabrera, the anthropologist whose work parallels his art. Cabrera’s 1954 book “El Monte” is often referred to as the “black bible” of Santería, and rightly so. Cabrera’s aim was indeed to preserve a theology. Like Lam, she refused to treat Afro-Cuban religion as mere superstition. She raised it to the level of sacred knowledge. Her research into the Abakuá, a secret male society descended from the Egbo people of Nigeria, resonates with Lam’s references to Egbo and Nañigo symbolism. Both Cabrera and Lam understood that secrecy was a necessity. The sacred is not always public.

They also shared a contempt for commercialization. Cabrera lamented how rituals were transformed into products. Lam refused to create “pseudo-Cuban music for nightclubs,” choosing instead to depict the “drama of his country” through the “Negro spirit.” This wasn’t just about artistic purity. It was about faithfulness to theology. Lam’s art does not celebrate Afro-Caribbean religion. It defends it.

Visitors can admire Lam’s “Omi Obini,” where a levitating figure hovers among sugarcane and palm leaves. Its body glows with translucent veils of green, blue, purple, ochre, and red. The untouched areas of the canvas seem to shimmer with Caribbean light, as if Lam were painting the very boundary between matter and spirit. Given that the work belonged to Lydia Cabrera, it is hard not to see that floating being as a portrait or at least a reference to Cabrera herself and her stated closeness with the Yoruba orishas.

As I walked through MoMA’s halls, I found myself back in my childhood living room, gazing at that “Untitled” painting and contemplating its message. I now believe it

was whispering the same message Lam conveyed to the colonizers: You cannot own what you cannot see. Lam’s dreamlike figures are not meant to be decoded. They are there to disturb the dreams of the exploiters. If you listen closely, you can still hear them speaking their mysterious words.

Massimo Introvigne (born June 14, 1955 in Rome) is an Italian sociologist of religions. He is the founder and managing director of the Center for Studies on New Religions (CESNUR), an international network of scholars who study new religious movements. Introvigne is the author of some 70 books and more than 100 articles in the field of sociology of religion. He was the main author of the Enciclopedia delle religioni in Italia (Encyclopedia of Religions in Italy). He is a member of the editorial board for the Interdisciplinary Journal of Research on Religion and of the executive board of University of California Press’ Nova Religio. From January 5 to December 31, 2011, he has served as the “Representative on combating racism, xenophobia and discrimination, with a special focus on discrimination against Christians and members of other religions” of the Organization for Security and Co-operation in Europe (OSCE). From 2012 to 2015 he served as chairperson of the Observatory of Religious Liberty, instituted by the Italian Ministry of Foreign Affairs in order to monitor problems of religious liberty on a worldwide scale.