Ren Zhengfei’s creation is more than just a company; it serves as a tool for the CCP’s global economic and political supremacy.

by Massimo Introvigne

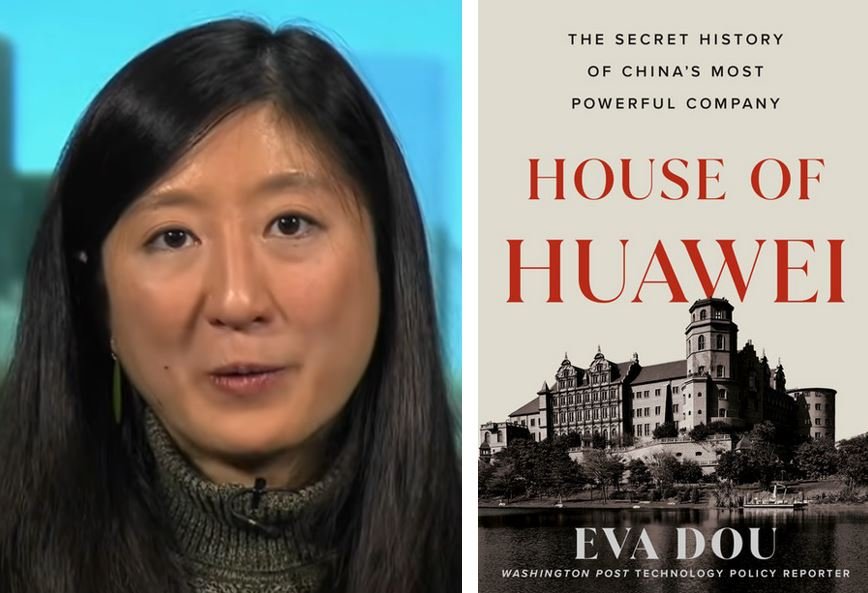

Eva Dou’s book, “House of Huawei: Technonationalism, Corporate Ascendancy, and State Symbiosis in Contemporary China” (New York: Portfolio, 2025), transcends traditional corporate biographies. It delves into the relationship between political power, national goals, and technological progress that characterizes China’s rise in the digital realm.

By documenting the journey of Huawei and its enigmatic founder, Ren Zhengfei, Dou, a “Washington Post” journalist, illustrates how the company’s worldwide triumph is intricately tied to the strategic objectives of the Chinese Communist Party (CCP). This provides a compelling case study of what she calls “technonationalism”: the intersection of national identity with technological supremacy.

Ren Zhengfei’s initial career in the People’s Liberation Army (PLA) shapes the ideological and operational framework for Huawei’s emergence. Although Huawei asserts it is a private enterprise owned by its employees via an “employee stock ownership plan,” Dou highlights the complexities of this narrative, given Ren’s strong military connections and allegiance to the CCP. His role as a military technologist during the Cultural Revolution—an era when engineers were frequently marginalized—granted him unique credibility within the Party and introduced him to the values of secrecy and discipline that would later become integral to Huawei’s culture.

This military background was crucial for Huawei as it entered China’s fragmented telecom market in the 1990s. Dou illustrates that while numerous competitors found it difficult to establish themselves, Huawei strategically put itself alongside government initiatives advocating to “buy Chinese,” positioning the company as a patriotic choice compared to Western telecom firms. This approach secured contracts and set Huawei on a path of state-supported expansion.

A particularly insightful aspect of Dou’s narrative focuses on the Party Committee embedded in Huawei’s corporate framework. Although many large Chinese companies have such committees, Huawei’s is depicted as especially dynamic in directing significant strategic choices and maintaining internal discipline. Dou notes that as Huawei grew internationally, it upheld an internal CCP structure that shaped its reactions to political challenges, notably amidst global criticism of its activities.

Dou examines how Huawei has maneuvered within the limits of China’s “civil-military fusion” policy, which requires private sector innovation to support national defense objectives. Although Huawei denies any direct military cooperation, its hiring of government researchers, involvement in state-funded initiatives, and role in developing surveillance systems imply a degree of integration with the security framework that Western firms might find troubling, if not unacceptable.

Dou asserts that Huawei serves as both a tool and a symbol of China’s industrial policy, benefiting from favorable bank loans from state policy banks and discreet backing in international diplomacy. She contextualizes the company within the “Made in China 2025” initiative and Beijing’s broader aims to surpass Western leadership in 5G, AI, and quantum computing.

Huawei’s participation in the Digital Silk Road—the technology-driven offshoot of the Belt and Road Initiative—is particularly noteworthy. Dou illustrates how Huawei executed telecom infrastructure projects across Asia, Africa, and Latin America, frequently managing them. This strategy provided China with geopolitical power and solidified Huawei’s international presence. These initiatives were seldom driven solely by commercial interests; Chinese embassies often engaged in talks, and host nations typically depended on Chinese funding linked to Huawei agreements.

A core tension in the book revolves around accusations of Huawei’s espionage activities. Dou avoids making conclusive statements but reveals circumstantial connections—such as products with remote access features, former employees linked to intelligence, and a lack of transparent corporate governance—that intensify global doubts. Meng Wanzhou, Ren’s daughter and Huawei’s CFO, was arrested in Canada at the U.S.’ request, escalating this skepticism into a geopolitical confrontation. China’s subsequent detention of Canadian citizens further complicated the distinction between a corporate issue and state politics.

Ren Zhengfei’s “wolf culture” concept promotes ruthlessness, loyalty, and sacrifice, profoundly influencing Huawei. His infrequent yet dramatic media appearances often fulfill two roles: reassuring international partners and demonstrating allegiance to the Party.

What unfolds is a tale of strategic partnership: Huawei flourishes as it supports the state, while the state promotes Huawei as it embodies China’s ambitions. Thus, “House of Huawei” is a narrative of corporate rise and a warning about the changing dynamics of Chinese capitalism under Xi Jinping, where distinctions between the Party and businesses grow ever fainter.

Massimo Introvigne (born June 14, 1955 in Rome) is an Italian sociologist of religions. He is the founder and managing director of the Center for Studies on New Religions (CESNUR), an international network of scholars who study new religious movements. Introvigne is the author of some 70 books and more than 100 articles in the field of sociology of religion. He was the main author of the Enciclopedia delle religioni in Italia (Encyclopedia of Religions in Italy). He is a member of the editorial board for the Interdisciplinary Journal of Research on Religion and of the executive board of University of California Press’ Nova Religio. From January 5 to December 31, 2011, he has served as the “Representative on combating racism, xenophobia and discrimination, with a special focus on discrimination against Christians and members of other religions” of the Organization for Security and Co-operation in Europe (OSCE). From 2012 to 2015 he served as chairperson of the Observatory of Religious Liberty, instituted by the Italian Ministry of Foreign Affairs in order to monitor problems of religious liberty on a worldwide scale.