The book has value and uncovers some disturbing connections, but ultimately collapses under the weight of its sweeping and unfair generalizations.

by Massimo Introvigne

Stewart Home’s latest polemic, “Fascist Yoga: Grifters, Occultists, White Supremacists, and the New Order in Wellness” (London: Pluto Press, 2025), storms into the burgeoning world of alternative health and spiritual practices with characteristic swagger—and unapologetic venom. Home, long known for his anarchist-nihilist takedowns of countercultural figures, has now turned his sights on modern yoga and its Western manifestations, arguing that much of it is ideologically compromised and historically tainted. The book is a blistering barrage of names, connections, and accusations, linking fascist sympathies, occult movements, self-help gurus, and seemingly innocent postural practices into a web of socio-political entanglements.

It’s a challenging and, at times, disturbing read. But while Home raises valid questions—and unearths some troubling historical connections—the book ultimately collapses under the weight of its sweeping generalizations and polemical fervor.

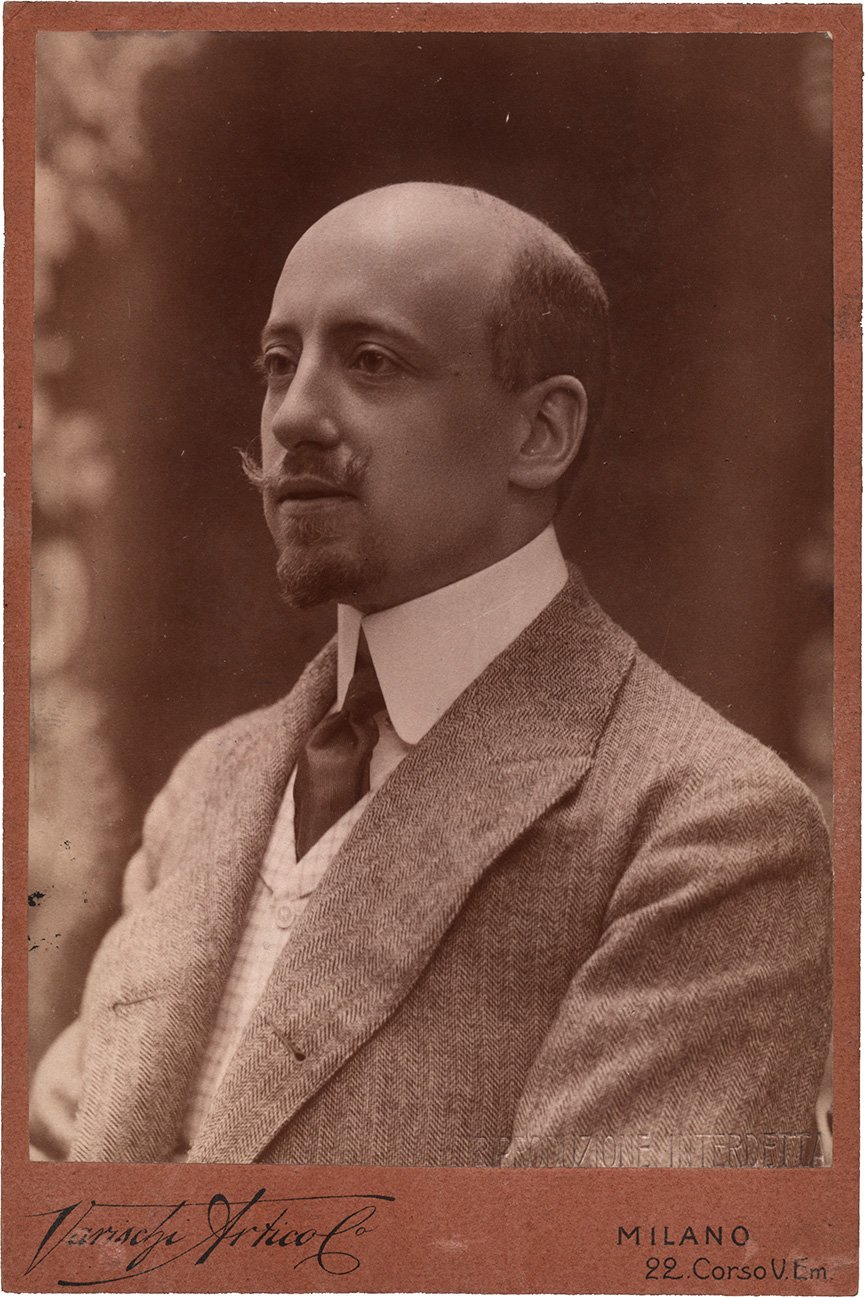

Home’s strength lies in excavation. The book bristles with citations and anecdotes, many of them surprising: details about the appropriation of yogic imagery by far-right groups, the path of forgotten right-wing yoga figures such as Francis Yeats-Brown, and the esoteric flirtations of Gabriele D’Annunzio and Mircea Eliade. He makes a credible case that Western receptions of yoga have occasionally served as vehicles for reactionary ideologies, whether through volkisch mysticism or neo-pagan aesthetics.

However, Home’s relentless focus on connections between yoga and fascism often results in misleading generalizations. Throughout the book, he insinuates that because some figures in yoga’s genealogical tree were sympathetic to fascist ideals, the entire tree is poisoned. Yet yoga —both in its postural and spiritual forms—spans a vast and diverse terrain. Speaking of “yoga” as a singular ideological movement betrays its historical complexity and global plurality.

Yes, some contemporary yoga influencers indeed deploy “spiritual bypassing,” reactionary wellness rhetoric, or nationalist Hindu tropes. But it is equally true that many yoga teachers and communities align themselves with liberal, anti-racist, feminist, and LGBTQ+ causes. The book’s omission of politically progressive yoga figures—such as Angela Farmer, Mark Whitwell, or Seane Corn, to name just a few—creates a skewed tableau, where yoga practitioners seem either dupes or demons.

One of the book’s more glaring limitations is its tendency to reduce complex thinkers to their fascist associations. D’Annunzio, Italian Futurism, and Eliade are given almost no nuance. D’Annunzio, for instance, was not merely a proto-fascist icon but a prolific poet and dramatist whose theatrical innovations and aesthetic influence transcended his political role. Italian Futurism, while at times complicit with fascist aesthetics, also included left-wing avant-gardists and was pivotal in shaping modernist literature and performance. Eliade, a leading historian of religion, certainly wrestled with troubling allegiances, but to read his entire corpus as a mask for fascism erases the philosophical and comparative depth of his scholarship.

Julius Evola, whose works on yoga Home references, was undoubtedly a fascist. However, reducing his teachings to “infamy” and instigation to “mass murder via bombing” is just political rhetoric, and ignores decades of studies on his multiple cultural and artistic influences by scholars who acknowledge and do not condone his racist and fascist activities. Even Aleister Crowley is studied in academia well beyond his political “temptations,” explored in a landmark study by Marco Pasi. However, Home would likely dismiss Pasi and other academics who have taught courses on Crowley as “revisionists.”

In Home’s account, ideological impurity seems unforgivable and irredeemable. However, cultural figures—especially those active during the volatile 20th century—often moved through ideological ambiguities. Flattening them into caricatures (and the scholars who refuse the caricature as “revisionists”) is not critique; it is moralistic erasure.

The book’s second part features a gallery of colorful, disreputable characters within the yoga subculture. However, they are not “fascist” in any substantial sense. Home explains that their commonality with fascists is their rejection of science, evident in their anti-vaccination stance during the COVID pandemic. A brief scan of social media reveals that many on the political left share these views, and not all on the right do. Additionally, Home hastily includes an unnecessary page about allegations against the Romanian yoga movement MISA and its leader, Gregorian Bivolaru, who is currently jailed in France. Based on press reports and a questionable BBC podcast, this information offers little new insight—only that Home has never studied MISA or understood why it attracted tens of thousands of followers.

Perhaps the book’s most provocative argument is its claim that modern yoga is a Western invention, a distortion of India’s spiritual legacy crafted for bourgeois bodies and neoliberal narcissism. This is not a new assertion—scholars like Mark Singleton (a yoga teacher himself), whom Home shortly mentions, have traced the development of postural yoga to early 20th-century gymnastic traditions and colonial hybridities. But Home weaponizes the claim to argue that all contemporary yoga is derived from the antics of Pierre Bernard, the “Omnipotent Oom,” in early 20th-century California—yet another exaggeration—, is inherently inauthentic, and a betrayal of the Indian roots.

This argument falters on two fronts.

First, Home largely ignores the reality that modern Indian yoga, in its mainline versions and well beyond some “charlatans” he mentions, has been shaped by Western ideas—from British physical education to Theosophy and transnational esotericism. As historian of Indian religions Keith Cantù cogently explains: “Western esotericism and yoga have long influenced each other, and claims to authenticity often obscure the ways in which modern Indian yoga has incorporated Western ideas. The discourse of authenticity, rather than clarifying origins, often serves ideological and political aims” (“‘Don’t Take Any Wooden Nickels’: Western Esotericism, Yoga, and the Discourse of Authenticity,” in “New Approaches to the Study of Esotericism,” edited by Egil Asprem and Julian Strube, Leiden: Brill, 2021, 109–26).

Second, by framing Western yoga as inherently “fascist,” Home erases the agency of Indian teachers who helped globalize yoga in the 20th century. Yogis such as B.K.S. Iyengar, Pattabhi Jois, and others all played roles in adapting yogic traditions for transnational audiences, often with eclectic borrowings and conscious reinventions. These adaptations complicate any easy moral narrative about cultural “betrayal.”

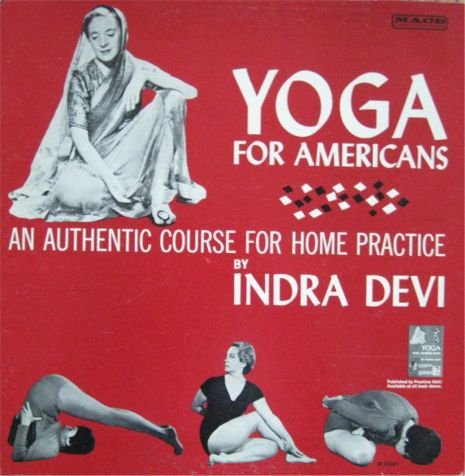

Home’s indictment of Indra Devi highlights his flawed perspective on the relationship between Indian and Western yogis. While Devi was born in Riga, Latvia, she learned yoga in India and gained a significant following there, not solely as a Bollywood actress.

Home’s tone suggests that hybridity is a crime and that spiritual transformation is valid only if it remains untouched by history. But yoga has constantly evolved—through Tantric sects, Shaiva mystics, and Vedantic philosophers. The idea of a timeless, pristine yoga is an invention, often used to police boundaries rather than open possibilities.

Where Home’s critique could have been generative, it becomes incendiary. By branding wellness influencers, conservative yoga practitioners, and esoteric seekers as “fascist,” he wields the term not analytically but rhetorically—as a cudgel. The inflation of the term “fascist” to encompass a wide variety of conservative, reactionary, or simply naive views does a disservice to both historical clarity and political debate.

It also risks alienating those who could be allies in resisting actual far-right infiltration of wellness culture. Blanket indictments rarely mobilize; they polarize.

There are, undoubtedly, disturbing intersections between certain wellness ideologies and authoritarian sympathies. The COVID-19 pandemic amplified these trends, as vaccine skepticism, bio-survivalism, and conspiracy narratives seeped into yoga communities. But to respond by declaring yoga itself a fascist endeavor is analytically unsound and culturally offensive, especially to millions of practitioners who find in yoga not coercion but care, not dogma but discovery.

Despite its flaws, “Fascist Yoga” has value. It provokes. It unearths stories many readers may have never encountered. It reminds us that spiritual movements are not immune to politics and that aesthetics can mask ideology.

But its failure lies in its lack of nuance, refusal to recognize countercurrents, and addiction to condemnation. Home wants to burn the field, not tend its complexity. While understandable in an age of political urgency, that impulse risks turning critique into crusade.

Those invested in yoga’s history or concerned about fascist aesthetics in spiritual culture should read the book with caution. It raises uncomfortable truths. But they must be sifted from exaggeration, contextualized with scholarship, and discussed with the respect that intellectual inquiry deserves.

Because what stands behind yoga is not a cabal of fascist grifters: it’s a multitude of seekers, teachers, scholars, and reformers. Their stories, too, deserve to be told.

Massimo Introvigne (born June 14, 1955 in Rome) is an Italian sociologist of religions. He is the founder and managing director of the Center for Studies on New Religions (CESNUR), an international network of scholars who study new religious movements. Introvigne is the author of some 70 books and more than 100 articles in the field of sociology of religion. He was the main author of the Enciclopedia delle religioni in Italia (Encyclopedia of Religions in Italy). He is a member of the editorial board for the Interdisciplinary Journal of Research on Religion and of the executive board of University of California Press’ Nova Religio. From January 5 to December 31, 2011, he has served as the “Representative on combating racism, xenophobia and discrimination, with a special focus on discrimination against Christians and members of other religions” of the Organization for Security and Co-operation in Europe (OSCE). From 2012 to 2015 he served as chairperson of the Observatory of Religious Liberty, instituted by the Italian Ministry of Foreign Affairs in order to monitor problems of religious liberty on a worldwide scale.