The forgotten meeting between the Victorian novelist and the South African religious and political activist—and Simon Magus’ excellent book on Haggard.

by Massimo Introvigne

Some months ago, while researching a book I co-authored on African spirituality (Massimo Introvigne and Rosita Šorytė, “The Revelation Spiritual Home: The Revival of African Indigenous Spirituality,” Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 2025), I found myself standing in the quiet, sun-drenched grounds of the Ohlange Institute in Inanda, near Durban, South Africa—a site steeped in history and memory. The museum devoted to John Langalibalele Dube, the first president of the South African Native National Congress, later to be renamed African National Congress, and a towering figure in African intellectual life, who coined the expression “African independent churches,” had drawn me in with its quiet dignity and powerful legacy.

Due to a remarkable coincidence, within just a few square miles around Inanda, three influential figures in South Africa’s religious and political history lived before World War I: Dube at the Ohlange School; Isaiah Shembe, who is at the origins of a whole family of African religious movements, in his holy city of Ekuphakameni, from 1911; and Mohandas K. Gandhi, the future Mahatma, at the Phoenix settlement he established in 1904 after moving to South Africa in 1893 and only leaving when he returned to India in 1914.

While the panels at Ohlange School and Gandhi’s nearby Phoenix settlement, now a museum, depict the three men, who knew each other, almost as friends, historians point out a less idealized reality. Dube shared anti-Indian sentiments with some of his political allies, and Gandhi was aware of this. Dube also saw Shembe as an intriguing but heretical founder of a new religious movement. Shembe met Dube several times but criticized his conservative theology and even questioned his moral integrity.

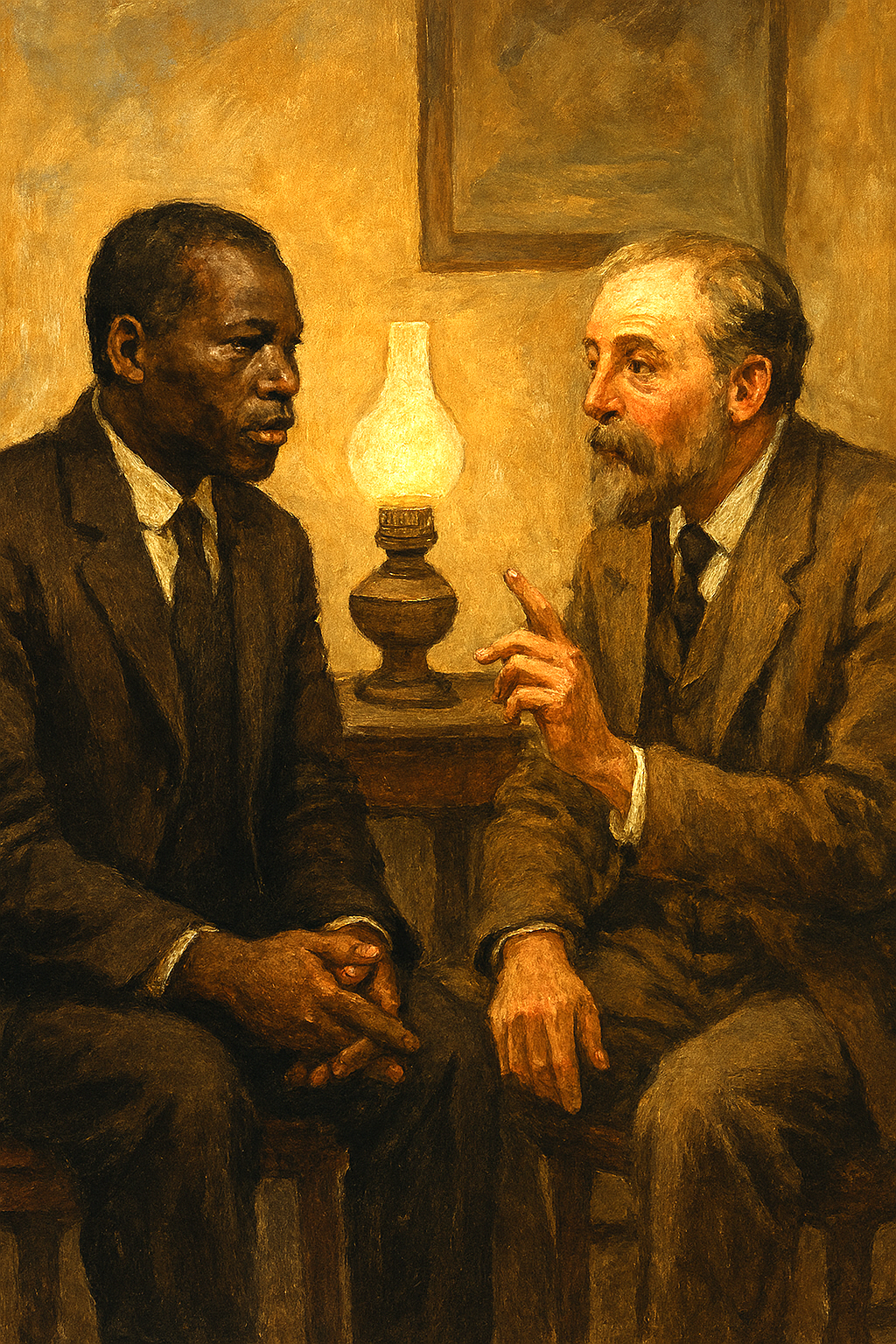

Something we mentioned in a first draft of our book but couldn’t include there because of space limits was the surprising and little-known meeting between Dube and English novelist Henry Rider Haggard in April 1914, mentioned on one of the museum’s panels and studied in depth by French scholar Patricia Crouan-Véron. Haggard, touring South Africa as part of the Royal Dominion Commission, met Dube at a politically tense moment—just after the Natives Land Act of 1913 was passed, which greatly restricted Black South Africans’ rights to own or rent land. Their conversation, though only briefly recorded, was symbolically meaningful: two men from very different worlds—one a colonial novelist steeped in esoteric lore, the other a Zulu intellectual and Christian minister (who also wrote novels)—talking about land, race, and identity in a country about to undergo significant change.

For Dube, the meeting offered a chance to articulate the grievances of Black South Africans to a prominent British figure with influence in imperial circles. Although Dube’s writings do not mention the meeting—likely due to the erasure of archives under apartheid—Haggard’s diary reveals that Dube expressed the deep pain and injustice felt by his people. It resonated with meetings Haggard had with other Zulu leaders, one of whom famously told him, “We black people are forced to eat the soil.” This powerful metaphor underscored the desperation caused by land dispossession. The exchange with Haggard may have reinforced Dube’s resolve to pursue political advocacy and education as tools for empowerment and resistance.

Haggard, known for his romanticized depictions of Zulu culture in fiction, was confronted with the real consequences of colonial policies. The meeting appears to have deepened his ambivalence about imperialism and prompted reflection on the moral contradictions of British rule. Though Haggard did not mention the encounter in his autobiography (but reported it at length in his journal for 1914, published in 2001 by Stephen Coan), Crouan-Véron suggests it influenced his later writings and public statements. The dialogue between these two men—one a colonial insider, the other a nationalist visionary—foreshadowed the long struggle for land restitution and racial justice in South Africa.

Another panel at the Inanda museum highlights that Dube played a key role in persuading F.L. Ntuli to translate Haggard’s novel “Nada the Lily” into isiZulu. He also wrote a preface, though his views on King Shaka differed from those of the British novelist. The same panel then questions whether Dube’s novel “Insila kaShaka,” which centers on Jeqe, Shaka’s bodyservant, and became a staple of Zulu literature, was influenced by Haggard’s literary style.

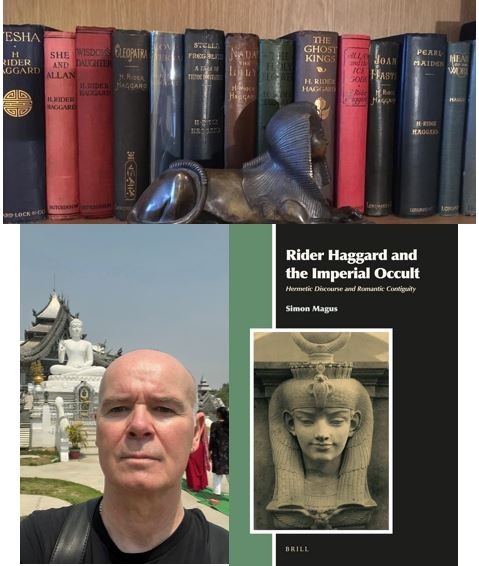

The visit to the Dube museum prompted me to return to Simon Magus’s “Rider Haggard and the Imperial Occult” (Leiden: Brill, 2021), a richly textured, intellectually daring study that perhaps slipped under many radars when it first appeared. I read it when it was published, and I was waiting for reviews by specialists of English literature who would be more conversant with Haggard than I am. I felt frustrated that the book didn’t receive all the reviews it merited.

Sir Henry Rider Haggard (1856–1925) was a British novelist best known for “King Solomon’s Mines” and “She,” two wildly popular adventure tales that helped define the “lost world” genre. Born in Norfolk, Haggard spent formative years in colonial South Africa, where he served as a government official and witnessed the annexation of the Transvaal. These experiences infused his fiction with imperial grandeur, exotic landscapes, and a fascination with ancient civilizations.

But Haggard was more than a spinner of yarns. He was a man haunted by metaphysical questions, drawn to the mystical and the arcane. His novels often feature immortal queens, secret initiations, and ancient wisdom hidden beneath the sands of empire. He was influenced by a constellation of esoteric thinkers and movements, including Egyptosophy (the belief that the ancient Egyptian religion contained esoteric and even proto-Christian truths), Theosophy, the British occult revival, but also Anglican scholasticism and the theological debates that questioned biblical literalism and opened the door to more symbolic readings of scripture.

Magus’s book explores how these influences shaped Haggard’s literary imagination, turning his adventure stories into allegories of spiritual quest and imperial anxiety.

Magus argues that Haggard’s fiction is best understood as part of the “imperial occult”—a cultural matrix in which colonial expansion, religious speculation, and esoteric traditions converged. Haggard’s protagonists don’t just explore Africa; they penetrate veils of illusion, encounter hidden truths, and undergo initiations that echo Hermetic rites.

Magus shows how Haggard reimagined ancient Egyptian religion through a Victorian Christian lens, creating a hybrid theology that fused resurrection myths with imperial ideology. He also traces how Haggard’s characters undergo spiritual transformations modeled on alchemical and Gnostic traditions. Ayesha, the immortal queen of “She”, becomes a symbol of hidden nature and initiatic death.

Magus deploys a dazzling array of theoretical tools—mnemohistory, narratology, reception theory—to illuminate Haggard’s texts as sites of cultural negotiation and spiritual yearning. He treats Haggard not as a relic of imperial kitsch but as a serious thinker whose works reflect the spiritual ferment of his age.

The book also resonates with contemporary debates about the role of esotericism in shaping modernity. It reminds us that the boundaries between religion, science, and fiction were far more porous than we often assume—and that adventure novels can be vehicles for profound metaphysical inquiry.

My encounter in Inanda with memories of Haggard’s meeting with Dube added a poignant layer to Magus’s book. It revealed Haggard not just as a spinner of imperial fantasies but as a man grappling with the moral contradictions of empire. Dube, meanwhile, emerged as a figure whose spiritual and political vision challenged the very foundations of colonial ideology. Their meeting, forgotten by most biographers and historians, deserves to be remembered—not only for its historical significance but for the way it illuminates the deeper currents of esoteric and political thought that Magus so deftly explores.

Magus’ book should have sparked deeper conversations across literary studies, religious history, and esotericism. If you missed it in 2021, now’s the time to catch up. It’s a richly rewarding read and a reminder that sometimes the most illuminating journeys begin with forgotten maps.

Massimo Introvigne (born June 14, 1955 in Rome) is an Italian sociologist of religions. He is the founder and managing director of the Center for Studies on New Religions (CESNUR), an international network of scholars who study new religious movements. Introvigne is the author of some 70 books and more than 100 articles in the field of sociology of religion. He was the main author of the Enciclopedia delle religioni in Italia (Encyclopedia of Religions in Italy). He is a member of the editorial board for the Interdisciplinary Journal of Research on Religion and of the executive board of University of California Press’ Nova Religio. From January 5 to December 31, 2011, he has served as the “Representative on combating racism, xenophobia and discrimination, with a special focus on discrimination against Christians and members of other religions” of the Organization for Security and Co-operation in Europe (OSCE). From 2012 to 2015 he served as chairperson of the Observatory of Religious Liberty, instituted by the Italian Ministry of Foreign Affairs in order to monitor problems of religious liberty on a worldwide scale.