Wei Wu’s new book offers a window into a captivating, enigmatic, and mostly unfamiliar aspect of Chinese Buddhism.

by Massimo Introvigne

In the early decades of the twentieth century, as China reeled from imperial collapse and raced toward modernity, a quiet revolution stirred in its monasteries and mountain academies. It wasn’t political, though it was deeply ideological. It wasn’t loud, though its echoes reached Tibet, Japan, and even the West. It was Esoteric Buddhism—reimagined, retranslated, and reborn.

Wei Wu’s “Esoteric Buddhism in China: Engaging Japanese and Tibetan Traditions 1912–1949 “(Columbia University Press, 2024) is not your average academic tome. It’s a portal into a world where ritual meets reform and Chinese monks and intellectuals became spiritual diplomats, negotiating the sacred across borders and centuries.

Forget the stereotype of Buddhism as serene and static. Wu’s research reveals a tradition in motion—charged with nationalism, shaped by geopolitics, and infused with tantric fire. Chinese reformers didn’t just borrow from Japan’s Shingon or Sōtō Zen schools. They turned to Tibet, embracing Vajrayāna rituals and scholastic rigor to craft a distinctly Chinese esoteric revival.

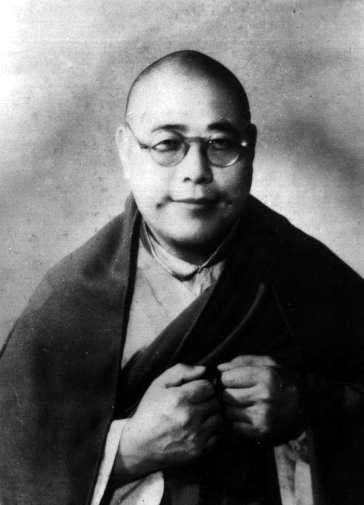

Take Nenghai (1886–1967), a charismatic monk who saw Tibetan tantra not as exotic ornamentation but as a key to restoring China’s spiritual legacy. With a scholar’s precision and a prophet’s passion, he translated texts, adapted rituals, and built bridges between traditions.

Then there’s Fazun (1902–1980), the intellectual powerhouse who translated Indian and Tibetan classics, championed Tsongkhapa’s philosophy, and argued that tantric sex rites—often scandalized by outsiders—were misunderstood and misrepresented. For Fazun, these practices weren’t immoral; they were mystical technologies reserved for the spiritual elite.

Wu’s book takes us to Mount Wutai, where the Sino-Tibetan Buddhist Institute trained monks in tantric liturgy, scripture, and discipline. But this wasn’t blind adoption—it was strategic adaptation. Chinese Buddhists weren’t passive recipients of foreign wisdom; they were curators, editors, and innovators.

And it wasn’t just monks. Lay practitioners, including women, played vital roles as translators, organizers, and even leaders. Wu’s attention to these often-overlooked figures adds texture to a narrative that’s as inclusive as it is intricate.

One of the book’s most provocative threads is how Buddhist reformers defended esoteric rituals against accusations of superstition. In an age obsessed with science and progress, they argued that tantra wasn’t irrational—it was psychologically astute, ethically grounded, and spiritually sophisticated.

Esoteric Buddhism, Wu shows, wasn’t a relic. It was a response. To colonialism. To Christianity. To modernity itself.

This isn’t just a story about monks and mantras. It’s about how traditions survive by transforming. It’s about the power of translation—not just of language, but of meaning. And it’s about how China, in the throes of reinvention, found a mirror for its complexity in the arcane symbols of tantra.

Wu’s book reminds us that the sacred is never fixed. It moves, adapts, and seduces. Sometimes, it takes the form of revolution—unless, as in China today, it is suppressed by an authoritarian regime. But that would be a topic for another book.

Massimo Introvigne (born June 14, 1955 in Rome) is an Italian sociologist of religions. He is the founder and managing director of the Center for Studies on New Religions (CESNUR), an international network of scholars who study new religious movements. Introvigne is the author of some 70 books and more than 100 articles in the field of sociology of religion. He was the main author of the Enciclopedia delle religioni in Italia (Encyclopedia of Religions in Italy). He is a member of the editorial board for the Interdisciplinary Journal of Research on Religion and of the executive board of University of California Press’ Nova Religio. From January 5 to December 31, 2011, he has served as the “Representative on combating racism, xenophobia and discrimination, with a special focus on discrimination against Christians and members of other religions” of the Organization for Security and Co-operation in Europe (OSCE). From 2012 to 2015 he served as chairperson of the Observatory of Religious Liberty, instituted by the Italian Ministry of Foreign Affairs in order to monitor problems of religious liberty on a worldwide scale.