The most famous anti-Masonic hoax is a cautionary tale to keep in mind when examining claims by anti-cult scholars about Satanic or “cultic” abuse.

by Massimo Introvigne

Article 1 of 4.

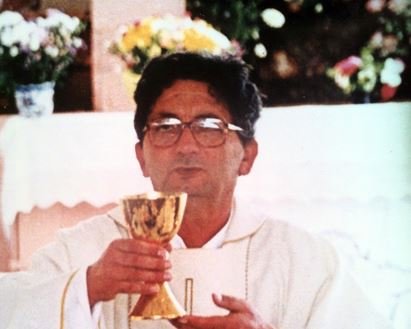

In the summer of 2025, an unexpected book reignited public interest in one of Italy’s most disturbing episodes of judicial overreach: the Satanism scare that led to the prosecution—and tragic death in 2000—of Father Giorgio Govoni. The case, once buried under layers of media sensationalism and prosecutorial zeal, had resurfaced thanks to a popular podcast by journalist Pablo Trincia.

The tragic episode unfolded in the 1990s in the province of Modena, where Father Govoni, a Catholic parish priest, became the target of extraordinary and unfounded accusations. A social worker, interpreting conversations with a four-year-old boy named Davide Tonelli Galliera, concluded that Govoni was leading a Satanic cult involving parishioners, in which children were sexually abused and murdered. No bodies were ever found, and no children were reported missing. Yet the social worker insisted that the “cult” used unregistered infants—allegedly born to “breeders”—as sacrificial victims.

I was called to serve as an expert witness for the Diocese of Modena, which was convinced of Father Govoni’s innocence. My analysis showed that the social worker’s claims mirrored sensational narratives drawn from questionable North American literature on ritual abuse, rather than anything grounded in local reality. Despite this, the prosecutor pursued the case with fervor. His closing argument was so aggressive that Father Govoni suffered a fatal heart attack in court and died shortly thereafter.

Although a few of the priest’s supposed accomplices were convicted in the first trial, both the appellate court and the Supreme Court of Cassation later issued rulings that implied Govoni had been wrongfully accused. The Diocese honored him as a martyr, and the town where he had served named a street after him. In 2017, a major Italian newspaper produced the Trincia podcast recounting the case, in which I was portrayed by an actor and consulted as a source.

Ultimately, the higher courts confirmed my argument: the accusations were baseless, and the social worker and prosecutor had erred. Tragically, this vindication came too late to save Father Govoni’s life.

In 2025, Davide Tonelli Galliera—the four-year-old “child zero” involved in the case of the 1990s, now an adult—published a sensational memoir revealing that he had been manipulated and threatened by the social worker as a child, and confirming that the alleged abuses had never occurred.

The Govoni case is emblematic of a broader international phenomenon, where ritual abuse scares led to the prosecution of innocent individuals. In Govoni’s situation, the existence of real sexual abuse cases involving other priests in the region unfairly colored perceptions. But the crimes attributed to Father Giorgio—and the supposed Satanic cult—were entirely fictional. This was one of those rare instances where an expert versed in Satanism and the anatomy of moral panics could help clarify the truth. Sadly, the truth arrived too late to prevent a tragedy, though it did restore Father Govoni’s honor posthumously.

While journalistic in tone, Trincia’s podcast and a companion book he wrote are refreshingly respectful of scholarly contributions. He praises those of us who, armed with archival rigor and a healthy skepticism, helped dismantle the myth of widespread Satanic ritual abuse. He also laments the role of certain scholars and activists who poured gasoline on the fire rather than cooling the flames.

Among those whose work inspired Father Govoni’s accusers and deserves a second look is Canadian sociologist Stephen Kent. Kent’s career has long been intertwined with the rhetoric of “dangerous cults,” and his early writings on Satanic ritual abuse (SRA) helped shape public perceptions in Canada and beyond. His recent evolution—from anti-cult scholar to outspoken critic of religion itself—has been documented in “Bitter Winter,” while his sweeping indictment of sacred texts as sources of abuse raised eyebrows even among secular academics. Kent’s trajectory invites a reexamination of his earlier claims, particularly those linking Satanism to deviant interpretations of religious scripture.

One historical case that comes to mind when assessing Kent’s work is that of Léo Taxil, the French provocateur whose elaborate hoax in the late 19th century convinced much of Europe that Freemasonry was a front for Satanic worship. Taxil’s story is not merely a cautionary tale—it is a blueprint for understanding how sensationalism, pseudonymous “eyewitnesses,” and ideological fervor can conspire to create a moral panic.

I’ve spent years researching Taxil, building on the foundational work of Jean-Pierre Laurant and Eugen Weber, and supplementing it with archival discoveries, culminating in my 2016 book “Satanism: A Social History” (Leiden: Brill, 2016). The chapter on Taxil offers what reviewers have called a near-definitive treatment of the affair (although I acknowledge that the brilliant thesis by Robert Rossi, “Léo Taxil [1854-1907]: Du journalisme anticlérical à la mystification transcendante,”also published in 2016 [Marseille: Quartiers Nord Éditions], adds further details).

Taxil, born in 1854 as Marie Joseph Gabriel Antoine Jogand-Pagès, began as an anticlerical journalist before orchestrating a grand mystification involving thousands of pages of fabricated testimonies, forged documents, and invented characters—most famously, the fictitious ex-Satanist Diana Vaughan.

Taxil’s hoax was so elaborate that it fooled the public and segments of the Catholic hierarchy. His books described secret Masonic rituals involving child sacrifice, sexual orgies, and invocations of Lucifer. These tales were presented as firsthand accounts, often attributed to anonymous or pseudonymous “survivors.” This would sound familiar to readers of Kent and other true believers in the 20th-century Satanic conspiracy, particularly because Kent even revived stories of ritual abuse by Freemasons.

Two lessons from the Taxil affair are particularly relevant to Kent’s work. First, the danger of taking sensational stories by alleged eyewitnesses at face value. Taxil’s “survivors” were figments of his imagination, yet their tales were accepted as gospel by those eager to believe. Second, not everything in Taxil’s corpus was fabricated. In a pre-Internet era, even hoaxers relied on existing printed sources. Taxil copied liberally from earlier literature, some containing kernels of truth. The problem was not the presence of factual elements, but their interpretation—twisted to fit a narrative of global Satanic conspiracy.

Kent’s writings on Satanism exhibit a similar pattern. He draws on historical precedents, religious texts, and survivor testimonies to construct a theory of “deviant scripturalism,” wherein sacred books are misused to justify abuse. In his two articles “Deviant Scripturalism and Ritual Satanic Abuse,” published in “Religion” in 1993, Kent argues that fringe groups have interpreted passages from the Bible and other religious texts to legitimize sexual violence. He cites the story of Lot and his daughters as a “classic scenario for incest.” He suggests that references to God as a heavenly father can be twisted to entrap followers in destructive faiths.

This line of reasoning, while provocative, is fraught with methodological pitfalls. It assumes a causal link between scripture and deviant behavior when the very existence of that behavior has not been proved. It also risks pathologizing religion itself—a tendency that has become more pronounced in Kent’s recent work, where he portrays several religions as breeding grounds for mental illness and abuse rather than multifaceted human phenomena.

Kent’s reliance on disgruntled ex-members to critique groups like the Church of Scientology and the Family Federation for World Peace and Unification (formerly the Unification Church) mirrors his approach to Satanism. He privileges anecdotal evidence over empirical rigor in both cases, constructing sweeping theories from isolated testimonies. This is not to say that all incidents referenced by Kent are false, just as not all of Taxil’s sources were invented. But the interpretive leap from individual experience to systemic pathology requires more than conviction; it requires evidence.

The parallel with Taxil becomes even more striking when we consider Kent’s views on Freemasonry. In interviews and articles, Kent has suggested that Masonic rituals may be linked to Satanic abuse—a claim that echoes Taxil’s most lurid inventions. While Kent stops short of endorsing a global Masonic conspiracy, his willingness to entertain such connections raises questions.

To be clear, Kent is not a hoaxer like Taxil. He is a credentialed academic. But like Taxil, he operates in a space where ideology can overshadow evidence, and where the allure of uncovering hidden evil can distort the lens of inquiry.

In this series, we will explore Kent’s role in the Satanism scare, his controversial theories, and the scholarly responses they have provoked. We will examine how his work influenced public policy, may have contributed to wrongful convictions, and shaped the discourse on religion and abuse. And we will ask whether Kent, like Taxil before him, has allowed the pursuit of truth to be eclipsed by the seduction of narrative.

The ghosts of the Father Govoni case remind us that ideas have consequences. When scholars lend credence to moral panics, they do more than misread history—they risk becoming part of it. Kent’s journey from sociologist to activist is a story worth telling, not because it is unique, but because it is emblematic of a broader tension between scholarship and sensationalism. After all, when the devil is in the details, the scholar must be doubly vigilant.

Massimo Introvigne (born June 14, 1955 in Rome) is an Italian sociologist of religions. He is the founder and managing director of the Center for Studies on New Religions (CESNUR), an international network of scholars who study new religious movements. Introvigne is the author of some 70 books and more than 100 articles in the field of sociology of religion. He was the main author of the Enciclopedia delle religioni in Italia (Encyclopedia of Religions in Italy). He is a member of the editorial board for the Interdisciplinary Journal of Research on Religion and of the executive board of University of California Press’ Nova Religio. From January 5 to December 31, 2011, he has served as the “Representative on combating racism, xenophobia and discrimination, with a special focus on discrimination against Christians and members of other religions” of the Organization for Security and Co-operation in Europe (OSCE). From 2012 to 2015 he served as chairperson of the Observatory of Religious Liberty, instituted by the Italian Ministry of Foreign Affairs in order to monitor problems of religious liberty on a worldwide scale.