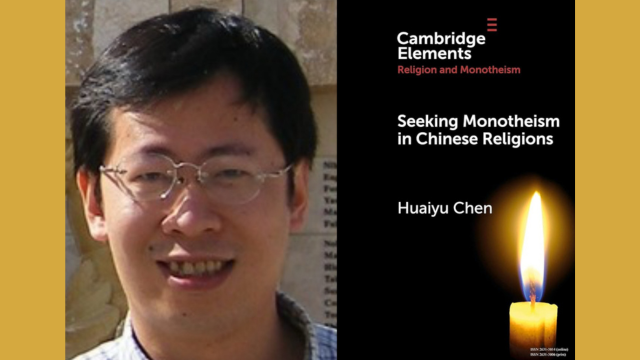

A dazzling little book by Chen Huaiyu shows how Baroque-era Jesuits and 19th-century Protestant missionaries scoured Chinese texts for signs of a pristine monotheism.

by Massimo Introvigne

If Indiana Jones traded his whip for a philological dictionary and swapped ancient tombs for dusty Confucian scrolls, he might resemble Arizona State University scholar Chen Huaiyu in “Seeking Monotheism in Chinese Religions” (Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 2025). This slim but intellectually muscular volume reads like a scholarly whodunit: did ancient China harbor a belief in one Supreme Being, and if so, who buried it beneath layers of ritual, myth, and imperial bureaucracy?

Chen’s central inquiry is deceptively simple: can we find traces of monotheism in the spiritual traditions of China? But the journey he takes us on is anything but straightforward. With the precision of a historian and the flair of a cultural anthropologist, Chen unpacks how, first, the Catholic Jesuits, then 19th– and early 20th-century Protestant missionaries—armed with Christian zeal and European philology—scoured Chinese texts for signs of a singular divine presence. Their goal? To prove that the Chinese, deep down, were proto-Christians waiting to be awakened.

Chen’s narrative centers on a compelling theological idea: the concept of degeneration from monotheism. Missionaries argued that ancient civilizations—from Persia to China—once worshipped a single God, but over time, this belief broke down into polytheistic pantheons.

As Italians were reminded by the most famous song by Franco Battiato (1945–2021; non-Italians can google “Centro di gravità permanente”), “Euclidean Jesuits / dressed like monks to enter the court of the Emperors” from Italy were the first to elaborate the idea of China’s original belief in a monotheistic God. The great Jesuit missionary Matteo Ricci (1552–1610) believed he was called “Shangdi” (the Sovereign on High) or “Tien” (Heaven). Another Italian Jesuit, Giulio (curiously, consistently misspelled in the book as “Guilio”) Aleni (1582–1649), focused on the name “Taiji” (the Great Ultimate). However, it was soon recognized that this term was not found in the older Confucian classics.

Chen effectively links these discussions to the Jesuits’ well-known appreciation for Chinese culture, a perspective not shared by other Catholic religious orders such as the Franciscans and Dominicans. These orders persuaded Pope Clement XI (1649–1721) to issue bans in 1704 and 1715 against the Jesuits’ acceptance of Chinese rites and the usage of the terms “Shangdi” and “Tien” for God. Instead, these terms were replaced by the more Christian-sounding “Tianzhu” (Lord of Heaven). This decision by the Pope deeply upset the Chinese Emperor, leading him to ban all missionaries from China. Missionaries would only return, under the protection of European warships, following the Opium War of 1840–42.

When Protestant missionaries began to enter China, Chen argues that they built upon the studies of the Jesuits, seeking an ancient Chinese understanding of monotheism that they believed had been later corrupted by foreign influences. Despite never visiting China, William Winterbotham (1763–1829) may have been the first Protestant scholar to adopt these ideas. The “Term Question”—concerning which Chinese term for “God” should be adopted to attract converts without compromising orthodoxy—created divisions among Protestant missionaries. They attempted to resolve this issue through conferences, the first of which occurred in Hong Kong in 1843; however, they ultimately concluded that their debates were unproductive.

They had differing opinions on the role of Confucius, the monotheistic aspects of the “state rituals” performed by the Emperors, and the specific forces that led to the degradation of monotheism into polytheism. In contrast to the Jesuits, they generally held a less charitable view of ancestor worship, considering it superstitious and polytheistic. As 19th-century archaeologists began to highlight the cultural exchanges between China and Persia along the Silk Road, Protestant Sinologists hypothesized that ancient Chinese monotheism might have originated from Iranian beliefs, suggesting that Shangdi was equivalent to Ahura Mazda, the highest god in Persian theology.

As Chen explains, missionaries shifted their focus from theology to sociology in the 20th century. They aimed to understand the changes occurring in Chinese society and the rise of nationalism and communism. Meanwhile, the theory of original monotheism continued to influence Western Sinologists and occasionally resurfaces in discussions even within China today.

Chen’s aim is not to determine whether the theory is historically accurate. Instead, he treats it as a cultural artifact, dissecting its assumptions and implications. He shows how these missionary interpretations were shaped not only by religious conviction but also by colonial ambition and orientalist fantasy. The missionaries weren’t just translating, they were transforming.

“Seeking Monotheism in Chinese Religions” is a dazzling little book that punches far above its weight. It isn’t just for theology nerds or Sinologists. It’s for anyone who’s ever wondered how ideas travel, mutate, and survive. Chen’s work reminds us that theology isn’t just about gods—it’s about language, power, and the stories we tell to make sense of the divine.

Massimo Introvigne (born June 14, 1955 in Rome) is an Italian sociologist of religions. He is the founder and managing director of the Center for Studies on New Religions (CESNUR), an international network of scholars who study new religious movements. Introvigne is the author of some 70 books and more than 100 articles in the field of sociology of religion. He was the main author of the Enciclopedia delle religioni in Italia (Encyclopedia of Religions in Italy). He is a member of the editorial board for the Interdisciplinary Journal of Research on Religion and of the executive board of University of California Press’ Nova Religio. From January 5 to December 31, 2011, he has served as the “Representative on combating racism, xenophobia and discrimination, with a special focus on discrimination against Christians and members of other religions” of the Organization for Security and Co-operation in Europe (OSCE). From 2012 to 2015 he served as chairperson of the Observatory of Religious Liberty, instituted by the Italian Ministry of Foreign Affairs in order to monitor problems of religious liberty on a worldwide scale.