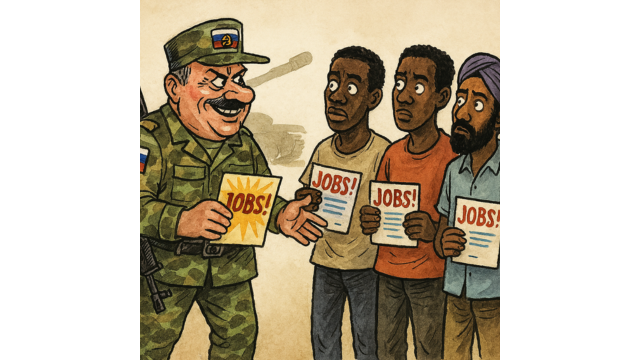

Recruited in their countries and told they will work in construction or domestic security, deceived immigrants from Africa and Asia are compelled to fight in the Ukrainian War.

by Massimo Introvigne

It’s not every day that a major European newspaper breaks a story that reads like a dystopian screenplay penned by a cynical bureaucrat with a taste for geopolitical theater. A few days ago, the Italian daily “Repubblica” did just that. It peeled back the curtain on what can only be described as a transcontinental scam of tragic proportions: the Kremlin’s recruitment—through deceit—of hundreds of men from Africa and Asia, who now find themselves trapped on the front lines of Russia’s war in Ukraine.

They were promised jobs. Construction work. Security gigs. A better life. Instead, they were handed rifles and sent to the trenches. Some were lured with contracts in Dubai or Moscow, only to be rerouted to military barracks. Others were offered Russian citizenship—a passport to nowhere—in exchange for service in a war they neither chose nor understood. The result? A Babel of conscripts from 106 countries, now prisoners of war in Ukraine, with no clear path home.

Let’s pause here. Because this isn’t just a story about war. It’s a story about branding. About how the Kremlin, ever resourceful, has turned the global South into a recruitment pool for cannon fodder—all under the guise of opportunity. It’s the militarized version of the bait-and-switch, with a dash of imperial nostalgia and a generous helping of moral bankruptcy.

And while the West frets over TikTok disinformation and AI-generated propaganda, Russia appears to have perfected the art of analog coercion. No bots required. Just a few forged contracts, a handful of recruiters, and the promise of escape from poverty—all leading to the same destination: the muddy fields of Donetsk.

These are not mercenaries. They are victims. Many come from countries with fragile economies and limited diplomatic leverage. Their governments, often unaware or unwilling to intervene, have left them stranded in a geopolitical limbo—pawns in a war that is increasingly outsourced, globalized, and grotesquely efficient.

And let’s not pretend this is new. Colonial powers have long recruited soldiers from the periphery to fight wars at the center. But what makes this moment particularly obscene is the scale and the opacity. There is no formal declaration, no recruitment office, no Geneva Convention briefing. Just a plane ticket, a promise, and a battlefield.

The irony? Russia, which rails against Western imperialism, is now running its own version—complete with a multinational army of the deceived. It’s the Kremlin’s answer to diversity: a front line that looks like the UN General Assembly, minus the consent.

Meanwhile, the men who survive—and are captured—sit in Ukrainian detention centers, bewildered and broken. Some speak of being forced to sign contracts under duress. Others recount being told they were joining a peacekeeping mission. One can only imagine the Kafkaesque realization that they were not building roads, but digging trenches.

And what of accountability? The Kremlin, predictably, denies everything. The recruiters vanish. The paperwork evaporates. And the international community, ever cautious, issues statements of concern. But concern doesn’t bring these men home. Nor does it prevent the next wave of deception.

This is not just a Russian problem. It’s a global failure. A failure of oversight, of diplomacy, of basic human decency. When war becomes a business model, and soldiers are sourced like cheap labor, we are no longer in the realm of politics. We are in the realm of trafficking.

So yes, let’s thank journalists who shine a light on this sordid chapter. But let’s also ask the hard questions. How many more are out there? How many recruiters are still operating? And how long before this model is replicated elsewhere by other regimes, in other conflicts?

Because if we don’t act, the next war won’t be fought by citizens. It will be fought by the duped, the desperate, and the disposable.

And that is not just a scandal. It’s a crime.

Massimo Introvigne (born June 14, 1955 in Rome) is an Italian sociologist of religions. He is the founder and managing director of the Center for Studies on New Religions (CESNUR), an international network of scholars who study new religious movements. Introvigne is the author of some 70 books and more than 100 articles in the field of sociology of religion. He was the main author of the Enciclopedia delle religioni in Italia (Encyclopedia of Religions in Italy). He is a member of the editorial board for the Interdisciplinary Journal of Research on Religion and of the executive board of University of California Press’ Nova Religio. From January 5 to December 31, 2011, he has served as the “Representative on combating racism, xenophobia and discrimination, with a special focus on discrimination against Christians and members of other religions” of the Organization for Security and Co-operation in Europe (OSCE). From 2012 to 2015 he served as chairperson of the Observatory of Religious Liberty, instituted by the Italian Ministry of Foreign Affairs in order to monitor problems of religious liberty on a worldwide scale.