“Apostate” is neither an insult nor a synonym of “ex-member.” It refers to the minority of ex-members who become militant critics of their former faith.

by Massimo Introvigne

Article 1 of 4.

On April 30, 2024, four United Nations Special Rapporteurs sent an official letter to the Japanese Government. These included those mandated by the UN for freedom of religion or belief, freedom of education, freedom of association, and freedom of expression. They had been alerted to a troubling situation in Japan. Consequently, they wrote to Japan’s Prime Minister, expressing their “serious concern” regarding what seemed to be “an emerging pattern of attacks and threats” against religious minorities in Japan, following the release of “Q&A on Responses to Child Abuse Related to Religious Belief.”

In Japan, a campaign depicted second-generation members of the Unification Church (currently known as the Family Federation for World Peace and Unification, though often called by its former name) and Jehovah’s Witnesses as “victims” of “religious child abuse” due to their restrictive and unsuitable education. This initiative resulted in regulations limiting parents’ rights to raise their children within conservative religious groups. On July 24, 2025, eight second-generation ex-members whose parents are part of the Unification Church filed a so-called “class action” seeking damages from the church for the alleged “psychological damage” suffered due to their education in the movement.

Although Japan’s situation is severe, it is not unique. An international campaign rekindles outdated anti-cult stereotypes, portraying second-generation members of new religious movements as “victims” who require “rescue.”

Ex-members who left their faith offer widely shared testimonies. This series outlines the scholarly definition of “apostates” and discusses research findings from the 20th century’s “cult wars.” It further contends that there is no justification for believing that second-generation apostates of the Unificatiin Church (and other religions) in Japan (and elsewhere) differ significantly from the first generation.

In its original sense, “apostasy” refers to leaving one religion to embrace another or atheism. This initial definition did not differentiate among the various stances and perspectives of individuals who abandoned a faith. However, with the emergence of modern sociology of religion, a new interpretation of the term “apostate” has developed. This more specific definition asserts that not everyone who departs from a faith qualifies as an apostate; only those who actively oppose their former beliefs and publicly denounce them are considered apostates.

The systematic examination of apostates originated from studies on new religious movements. Scholars in this field, as Stuart Wright pointed out in 1988, made a “curious discovery”: there was a “paucity of data,” and the sociological study of apostates was “astoundingly scant.” While historians had explored prominent 19th-century ex-Catholic and ex-Mormon apostates, sociological theory before the 1970s was somewhat limited.

It is no coincidence that scholars studying new religious movements focus significantly on the issue of apostates. The anti-cult movement systematically leveraged apostates to demonstrate that groups it branded as “cults” were harmful. Although the anti-cult movement failed to gain traction in academia—where only a few scholars accepted its claims that “cults” were not “real” religions and employed brainwashing to attract followers—it found considerable success in the media.

Stories from apostates about religions deemed as “cults” quickly captured the attention of journalists. In contrast to the nuanced analyses of scholars, these narratives offered clear-cut tales featuring identifiable heroes (the apostates and anti-cult activists) and villains (cult leaders and, occasionally, scholars who challenged the credibility of the apostates). These accounts also included sensational tales of abuse, making them particularly engaging.

Building on earlier frameworks established by David Bromley, a renowned academic authority on apostasy, researchers have classified three categories of ex‑members from new religious movements: defectors, ordinary leave-takers, and apostates.

Type I narratives characterize the exit process as defection. According to Bromley, “The defector role may be defined as one in which an organizational participant negotiates exit primarily with organizational authorities, who grant permission for role relinquishment, control the exit process, and facilitate role transition. The jointly constructed narrative assigns primary moral responsibility for role performance problems to the departing member and interprets organizational permission as commitment to extraordinary moral standards and preservation of public trust.”

In Type I cases, the departing members recognize their inability to meet the organization’s standards. They feel a sense of failure attributed to personal challenges and regret not being able to remain in an organization they still regard as benevolent and morally principled.

Type II narratives—ordinary departures—are the most prevalent yet least addressed. Participants leave various organizations daily, but little is discussed about the processes involved unless conflicts arise. Non-contentious exits involve little negotiation among departing individuals, the organizations they leave, and the broader social context.

Modern society often shares a straightforward narrative: as someone transitions from one social “home” to another across different fields, they typically lose interest, loyalty, and commitment to their past experiences while embracing new ones. In this framework, a standard Type II narrative illustrates that ordinary leavers do not maintain strong ties to their previous experiences. Furthermore, ordinary departures usually do not require extensive justification, and there is seldom a thorough investigation into the underlying reasons and responsibilities of the exit process.

Type III narratives outline the function of the apostate. Here, former members significantly shift their allegiances and become “professional enemies” of the organization they abandoned. In Bromley’s terms, “The narrative is one which documents the quintessentially evil essence of the apostate’s former organization, chronicled through the apostate’s personal experience of capture and ultimate escape/rescue.”

The previous organization would label the apostate as a traitor without hesitation. Yet, the apostate, especially after becoming part of an oppositional coalition against the organization, frequently embraces the image of the “victim” or a “prisoner” who did not join willingly. Once socialized into the opposing coalition by anti-cult movements, the apostate discovers various theoretical frameworks, including compelling brainwashing metaphors, that effectively illustrate why the organization is malevolent and how it strips its members of their free will.

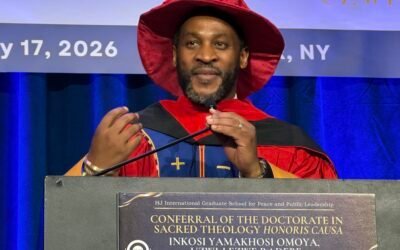

Massimo Introvigne (born June 14, 1955 in Rome) is an Italian sociologist of religions. He is the founder and managing director of the Center for Studies on New Religions (CESNUR), an international network of scholars who study new religious movements. Introvigne is the author of some 70 books and more than 100 articles in the field of sociology of religion. He was the main author of the Enciclopedia delle religioni in Italia (Encyclopedia of Religions in Italy). He is a member of the editorial board for the Interdisciplinary Journal of Research on Religion and of the executive board of University of California Press’ Nova Religio. From January 5 to December 31, 2011, he has served as the “Representative on combating racism, xenophobia and discrimination, with a special focus on discrimination against Christians and members of other religions” of the Organization for Security and Co-operation in Europe (OSCE). From 2012 to 2015 he served as chairperson of the Observatory of Religious Liberty, instituted by the Italian Ministry of Foreign Affairs in order to monitor problems of religious liberty on a worldwide scale.