2025 marks the 100th anniversary of Kafka’s “The Trial.” This book’s essence resonates profoundly with the experience of Tai Ji Men.

by Massimo Introvigne*

*Introduction to the webinar “The Tai Ji Men Case: Tragedy and Triumph,” co-organized by CESNUR and Human Rights Without Frontiers for the 18th anniversary of Taiwan’s 2007 Supreme Court decision in favor of Tai Ji Men, July 13, 2025.

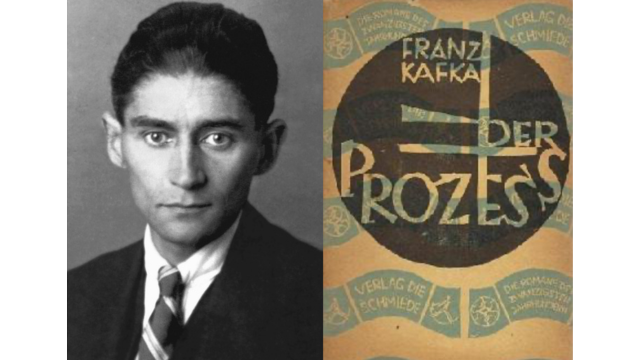

As we celebrate the 18th anniversary of Tai Ji Men’s historical victory at Taiwan’s Supreme Court, literary historians around the world are also commemorating another significant milestone: the one-hundredth anniversary of the posthumous publication of Franz Kafka’s novel “The Trial” in 1925.

Franz Kafka began writing “The Trial” in 1914, but his work was interrupted by World War I. He had not finished the book by the time of his death in 1924. Kafka often destroyed his unpublished manuscripts, but fortunately, his friend Max Brod saved “The Trial” and published it a year after Kafka’s passing. Today, the novel is considered one of the most influential works in Europe’s literary and cultural history.

This novel introduced the term “kafkaesque” to the English language, describing the surreal, confusing, and frightening experiences of individuals facing the seemingly irrational actions of judges and bureaucrats. This concept precisely reflects the situation of Tai Ji Men in Taiwan.

“The Trial” is a haunting exploration of bureaucracy, guilt, and the elusive nature of justice. The story follows Josef K., a respectable bank clerk who finds himself arrested one morning without being informed of the charges against him. Despite his efforts to understand his situation and defend himself, he becomes entangled in an opaque legal system that provides no clarity, resolution, or escape. The novel concludes with Josef’s execution, still without him ever discovering the nature of his alleged crime.

At its core, “The Trial” is a parable about the individual’s powerlessness when faced with an impersonal and impenetrable authority. Kafka’s portrayal of the legal system does not depict overt tyranny, but rather maddening ambiguity. The court operates without explanations; its officials are anonymous and contradictory, and its procedures remain obscure. Josef K.’s attempts to navigate this system—through lawyers, experts, and even romantic relationships—only deepen his confusion and despair.

What makes “The Trial” enduringly relevant is its depiction of a world where processes overshadow purpose, and the machinery of justice and bureaucracy becomes an end in itself. In today’s context, many citizens encounter legal and bureaucratic systems that feel similarly arbitrary and inaccessible. Particularly in tax cases, individuals can find themselves caught in procedures that seem to operate according to their own logic, detached from transparency or accountability.

Kafka’s vision resonates especially in instances where courts or state agencies make decisions that appear quirky, inconsistent, or irrational. Confronted with the contradictory behavior of Taiwanese judges and tax authorities, the dizi (disciples) of Tai Ji Men felt as bewildered and powerless as Josef K. The novel captures the psychological toll such encounters impose on the dizi: the sense that their fates are being determined by unjust forces beyond their comprehension.

Kafka’s almost clinical prose intensifies the sense of dread. He does not indulge in melodrama; instead, the horror lies within the mundane. The guards who arrest Josef are polite. The court officials are not sadistic; they are simply indifferent. This subtle, bureaucratic violence is what makes the novel chilling—and all too familiar for those acquainted with the Tai Ji Men case.

“The Trial” remains a powerful allegory for the kafkaesque condition faced by those who encounter legal and bureaucratic injustices, as experienced by Tai Ji Men. Kafka speaks to the dizi who feel overwhelmed by systems they cannot comprehend or influence. While he does not offer solutions, Kafka provides recognition—and in that, a form of solidarity.

Josef K.’s bewilderment is not solely his own; it reflects the predicament of the dizi, and it resonates with all of us.

Massimo Introvigne (born June 14, 1955 in Rome) is an Italian sociologist of religions. He is the founder and managing director of the Center for Studies on New Religions (CESNUR), an international network of scholars who study new religious movements. Introvigne is the author of some 70 books and more than 100 articles in the field of sociology of religion. He was the main author of the Enciclopedia delle religioni in Italia (Encyclopedia of Religions in Italy). He is a member of the editorial board for the Interdisciplinary Journal of Research on Religion and of the executive board of University of California Press’ Nova Religio. From January 5 to December 31, 2011, he has served as the “Representative on combating racism, xenophobia and discrimination, with a special focus on discrimination against Christians and members of other religions” of the Organization for Security and Co-operation in Europe (OSCE). From 2012 to 2015 he served as chairperson of the Observatory of Religious Liberty, instituted by the Italian Ministry of Foreign Affairs in order to monitor problems of religious liberty on a worldwide scale.