Vampires and comics, death and immortality. The book’s introduction took Catania’s Etna Comics by storm.

by Marco Respinti*

*An Italian version of this article was published in the daily newspaper “Libero” on June 12, 2025, as “Tornano i vampiri eterno mito di vita amore e morte.”

A few days ago, a horde of vampires stormed Catania during the comic convention Etna Comics 2025. Vampires are a deadly serious matter, warns Il Tempio della Nona Arte (The Temple of the Ninth Art), the publishing house-cum-association in Acireale, which also runs a library in Santa Lucia del Mela, in the Messina area, with over 60,000 comic books.

For Etna Comics, the Tempio has unveiled a portfolio in 100 numbered copies with a simple descriptive title, “Vampiri” (Vampires). It includes portraits of classic vampires and notes about their comic book versions: Sheridan LeFanu’s sapphic Carmilla, the bewitching Vampirella by Forrest J. Ackerman, the Twilight saga by Stephanie Meyer, the TV series Buffy the Vampire Slayer by Joss Whedon, the Donald-Duck-like vegetarian vampire Duckula, with ketchup in his vein instead of blood, and others, including, of course, Dracula, the count from Transylvania and the king of vampires.

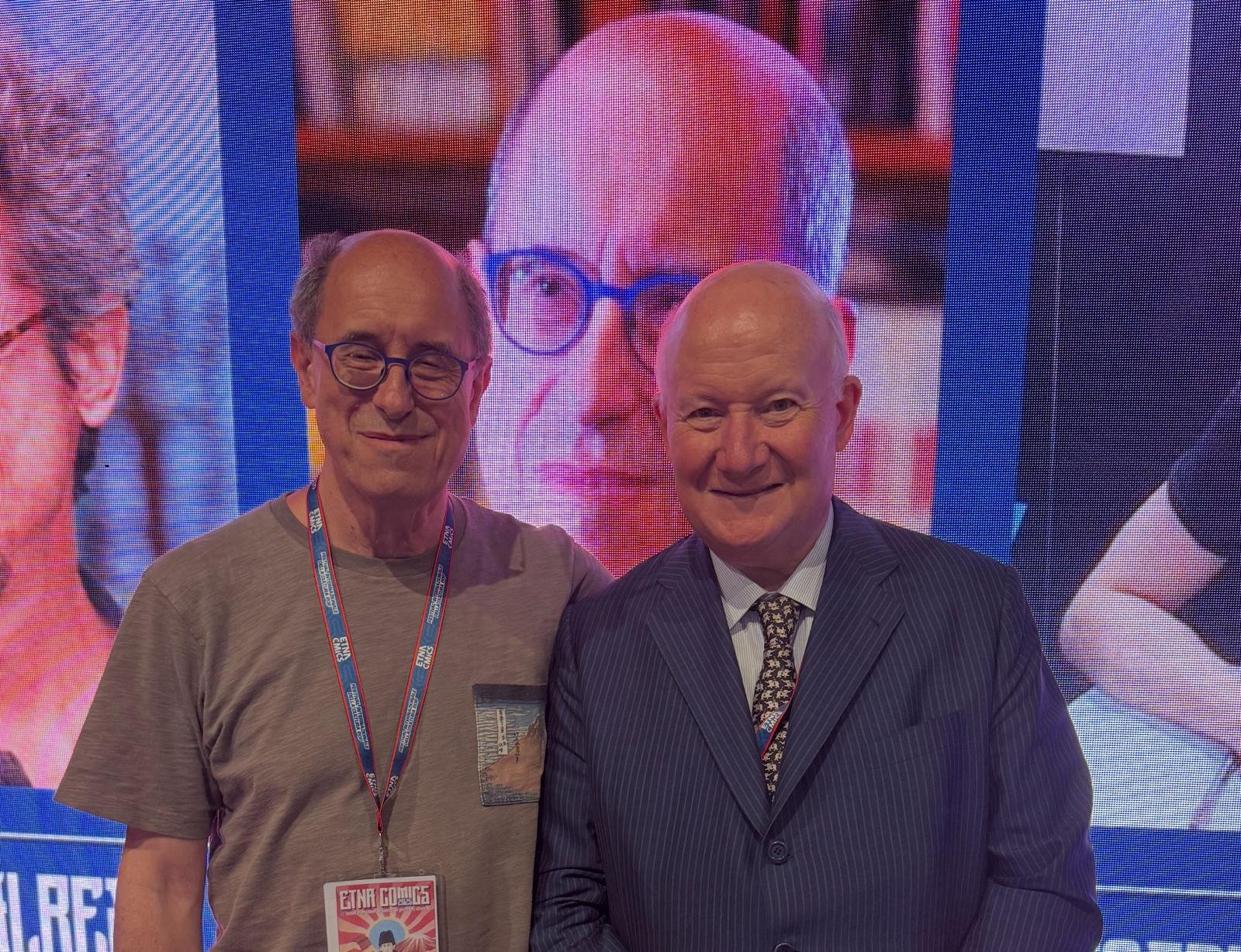

The original illustrations are by Giacomo Porcelli. He is a comic artist and a sculptor who works with the famous ceramics of Caltagirone and lava stone. He designed the logo for the centenary celebrations of Italian special effects designer Carlo Rambaldi, the winner of three Academy Awards, who was born in 1925 and died in 2012.

The texts of “Vampiri” are by Massimo Introvigne. But what does Introvigne, a renowned scholar of religion and one of the world’s leading experts on new religious movements, an academic who has authored some seventy books, have to do with vampires? The answer lies in his book “La stirpe di Dracula” (Dracula’s Progeny, Milan: Mondadori, 1997), a scholarly book on the myth of the vampire, our fear of death, and how we come to terms with the afterlife.

At this point, readers would expect the usual rigmarole about Umberto Eco, the semiotics of pop and vernacular culture, the deformities of communication in the age of the masses, comics as a form of culture and even of democracy. All this remains, of course, relevant. However, in “myth of the vampire,” the operative word is “myth.” It is about a symbolic and stubborn questioning of life, death, the soul, and the divine. In an age of global disenchantment, there have been attempts at eradicating the myth with the exorcisms of the Enlightenment. However, the myth knows how to hide and go underground as a karstic river, only to reappear and spread rampantly in new forms wherever it finds space. These new forms are comics, genre literature, music, cinema, and TV series with a “liturgical” pace, as if everything were always in full swing, even games (card, board, role-playing, and video games).

Scandalously heretic amid the well-ironed folds of modernity, the myth of the vampire provokes us between remorse, redemption, and our yearning, often in vain, to be loved.

The vampires do not reflect in the mirror, nor can they be photographed, because nobody knows where their souls ended up. Introvigne maintains that the vampire inhabits countries devoid of the liberating notion of Purgatory. In Catholic countries, there is only a minimal mythology of the vampire because the souls not good enough for Paradise nor bad enough for Hell have a place to go, Purgatory. In Protestant and Orthodox countries, there is no Purgatory—and there are plenty of vampires. Bram Stoker, the author of “Dracula,” was Irish but not Catholic.

Perhaps dealing with the myth of the vampire today is a practical and even ascetic exercise. We try to avoid myths, but then we end up at the analyst’s. Because, as the portfolio book explains, vampires can only enter our homes if we invite them in.

Marco Respinti is an Italian professional journalist, member of the International Federation of Journalists (IFJ), author, translator, and lecturer. He has contributed and contributes to several journals and magazines both in print and online, both in Italy and abroad. Author of books and chapter in books, he has translated and/or edited works by, among others, Edmund Burke, Charles Dickens, T.S. Eliot, Russell Kirk, J.R.R. Tolkien, Régine Pernoud and Gustave Thibon. A Senior fellow at the Russell Kirk Center for Cultural Renewal (a non-partisan, non-profit U.S. educational organization based in Mecosta, Michigan), he is also a founding member as well as a member of the Advisory Council of the Center for European Renewal (a non-profit, non-partisan pan-European educational organization based in The Hague, The Netherlands). A member of the Advisory Council of the European Federation for Freedom of Belief, in December 2022, the Universal Peace Federation bestowed on him, among others, the title of Ambassador of Peace. From February 2018 to December 2022, he has been the Editor-in-Chief of International Family News. He serves as Director-in-Charge of the academic publication The Journal of CESNUR and Bitter Winter: A Magazine on Religious Liberty and Human Rights.