During its long history, the Shrine met with problems and scandals but became also extremely popular for his philanthropic activities.

by Massimo Introvigne

Article 2 of 3. Read article 1.

Having fun, drinking and taking part in grand parades were some of the reasons for the Shrine’s extraordinary success among American Freemasons, to which Fleming’s first successor, Sam Briggs (1841–1904), made a major contribution. There were 340,000 members in 1938 and over a million in the 1960s. Four US presidents—Warren G. Harding (1865–1923), Franklin Delano Roosevelt (1882–1945), Harry Truman (1884–1972) and Gerald Ford (1913–2006)—and four Mexican presidents—Porfirio Díaz (1830–1915), Pascual Ortiz Rubio (1887–1963), Abelardo Rodriguez (1889–1967) and Miguel Alemán Valdés (1900–1983)—were Shriners. President Ronald Reagan (1911–2004) accepted the title of Honorary Shriner. Among the ranks of Shriners were several generals, judges and actors—including Harold Lloyd (1893–1971), who was even Imperial Potentate in 1949-1950. Early Shriner actors included Roy Rogers (1911–1998), Red Skelton (1913–1997) and Dick Powell (1904–1963). John Wayne (1907–1979) and Clark Gable (1901–1960) were also Shriners, as was Buffalo Bill (William Cody, 1846–1917).

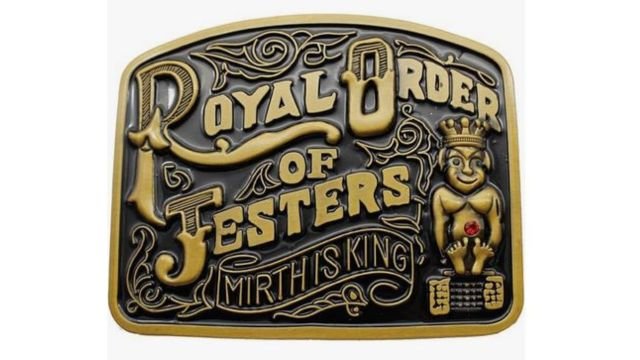

Excessive amusements and liquors, and the presence of dancers at Shriner meetings, repeatedly provoked reactions from the Masonic authorities. The most serious problems concerned the “Royal Order of Jesters,” a rather exclusive inner circle of the Shrine founded in 1911 to keep the pure spirit of amusement above any esoteric involvement. The Jesters, to whom the Shrine’s highest dignitaries have traditionally belonged, have been implicated several times in prostitution cases, notably in the 2000s in connection with “fishing trips” to Brazil, where some of them allegedly visited under-age prostitutes.

During its long history, the Shrine met with problems and scandals but became also extremely popular for his philanthropic activities.

Understandably, the Shriners’ women were quick to ask to participate in their activities. Two auxiliary organizations for Shriners’ wives and daughters were born, the “Ladies Oriental Shrine of North America” in 1903, and the “Daughters of the Nile” in 1913. The Shriners initially opposed these organizations, as they considered the Shrine spirit and sociability typically masculine, but eventually accepted them.

Despite its problems, the Shrine is extremely popular in the USA for its charitable activities. It was Imperial Potentate W. Freeland Kendrick (1873–1953), future mayor of Philadelphia, who established the Shriners Hospitals for handicapped children in 1920. Today there are 22 hospitals in North America, particularly specialized in the treatment of childhood burns. Their assets were valued at $9.3 billion in 2013, but have since shrunk as a result of the international economic crisis. Charity American soccer matches are organized by the Shrine, which also has its renowned circuses, where tickets devolve to hospitals. And Shriners learn to put on clown shows, which they then offer to children in their hospitals.

The Shrine is also involved in artistic initiatives, especially on the theme of peace. In 1930, it presented the City of Toronto with the Peace Memorial, created by American sculptor Charles Keck (1875–1951), himself a Shriner. During the Cold War era, the Shrine played an active role in anti-Communist campaigns. Encouraged by FBI Director John Edgar Hoover (1895–1972), an active and enthusiastic Shriner as was President Truman, the order even formed secret units to denounce anti-American infiltration into the USA.

Today, the Shrine has shrunk from over a million members to just 300,000. It has responded by trying to establish itself outside North America, and in 2010 changed its name to Shriners International. The change of name dropping “Ancient Arabic Order” and the elimination of some of the Islamic-sounding trappings was also due to the unpopularity of Islam after 9/11, which even led to Shriners be mistaken for Muslims and attacked in the streets as such.

Since 2000, all you need to become a Shriner is to be a Master Freemason, whereas previously you had to be a 32nd or 33rd degree Freemason (or a Knight Templar in the York Rite). But Freemasonry in the USA has also shrunk in membership in the US, and it’s increasingly difficult to get young people interested.

Where’s Islam in all this? The architecture of Shrine sanctuaries, where temples often have names like Mecca, Al Koran or Medinah, retains its Arabizing style, and there’s always a bit of Quran in the rituals, notwithstanding the post-9/11 “de-Arabization.” The official (mythical) history of the order stated that it “does not profess Mohammedanism as a sect, but teaches here the same respect for God as in Arabia.” For the good Protestants who are the majority of Shriners, Islam was merely a symbolic language, and today perhaps not even this. But there have been exceptions in the African-American version of the Shrine, as we will see in the next article of this series.

Massimo Introvigne (born June 14, 1955 in Rome) is an Italian sociologist of religions. He is the founder and managing director of the Center for Studies on New Religions (CESNUR), an international network of scholars who study new religious movements. Introvigne is the author of some 70 books and more than 100 articles in the field of sociology of religion. He was the main author of the Enciclopedia delle religioni in Italia (Encyclopedia of Religions in Italy). He is a member of the editorial board for the Interdisciplinary Journal of Research on Religion and of the executive board of University of California Press’ Nova Religio. From January 5 to December 31, 2011, he has served as the “Representative on combating racism, xenophobia and discrimination, with a special focus on discrimination against Christians and members of other religions” of the Organization for Security and Co-operation in Europe (OSCE). From 2012 to 2015 he served as chairperson of the Observatory of Religious Liberty, instituted by the Italian Ministry of Foreign Affairs in order to monitor problems of religious liberty on a worldwide scale.