Most scholars have abandoned a word that has no definition and no borders. It is used only as a derogatory term to stigmatize “the other.” Yet, in Japan it is still current.

by Marco Respinti*

Article 2 of 4. Read article 1.

*Under the title “The Crisis of Religious Freedom and Democracy in Japan,” this paper was presented in different versions at conferences organized and hosted in December 2024 by the International Coalition for Religious Freedom (ICRF) Japan Committee and constituting a lecture tour in Japan that brought the author to speak at Bunka Koryu Kaika, in Hiroshima, on the 6th, at Tokyo City Vision Center in Tokyo Kyobashi on the 8th, at Niterra Civic Hall in Nagoya, on the 9th, and at ACROS Fukuoka, in Fukuoka, on the 10th.

The Unification Church is a new religious movement, founded in South Korea in 1954 by Rev. Moon Sun Myung (문선명, 1920–2012). It has known an important success in this country, Japan, among many others. Particularly after another and different religious group called Aum Shinrikyō perpetrated several crimes, including a lethal terrorist attack with sarin gas against the Tokyo subway in 1995, new religious movements, and sometimes religions and religion in general, are perceived by many Japanese as a problem rather than as a resource.

Those criminal acts by Aum Shinrikyō sparked a sentiment of general hostility against those creeds that are defined—maliciously or for an unbearable ignorance—as “cultic,” “fanatic,” and chronically connected to the idea of violence, even if in most cases those groups are totally peaceful. This is particularly true for new, not well-known, or small religious groups or spiritual schools, even if the three adjectives I just used may not always be present. In fact, a “new religion” can be a small group even if it is well-known, and the reverse is true as well.

New, not well-known, or small religious groups are often also referred to as “cults.” Social agitators part of the so-called anti-cult movement insist their campaigns are against “cults” only. But the fact is, this is not always true. Sentiment against religion in general may well begin by addressing “cults,” but it is soon generalized, and this because “cult” itself is a problematic concept. It is not a scientific word, and most scholars refrain from using it. Indefinite in its meaning and borders, it complicates things rather than simplifying them. What does distinguish in fact a “cult” from a “legitimate” religion? Who draws the line, and based on which criteria? Can a set of laws, a code, or a secular state enter into the complex and sometimes complicated theologies, liturgies, and histories of groups whose mentality they barely understand?

The use of the world “cult” is in fact always derogatory and serves to label rivals or people that an individual or an organization or an institution or a state dislike. It indicates always “the other” and is cast on people and groups without any proof. In sum, a “cult” results always to be what the person, organization, institution, or state using that word against a religious or spiritual group make that word mean.

Also, “cults” are accused of “brainwashing” to control their “victims,” but also this notion has been widely rejected as pseudo-scientific by the vast majority of scholars who study new religious movement in the West, and by courts of law in the U.S. and other countries. Yet, this does not seem to be generally known in Japan, as not very well known is also the opposition by a large part of the scholarly community to the “anti-cult” narrative prevailing in the media. In fact, in Japan there is no parallel to that reaction, as most scholars of religion are afraid to jeopardize their careers by being associated with “cults,” as it happened to some of them who had naively supported Aum Shinrikyō.

It is also important to note that the anti-cult movement in Japan was not born in a vacuum. For historical reasons I have no time to elaborate on here, since the French Revolution, French governments have been suspicious of religion in general and of religious minorities they see as difficult to control in particular.

There are governmental agencies in France whose mandate is to fight “cults” and even to promote the anti-cult ideology internationally. “The Journal of CESNUR” has noted that these agencies and Japanese lawyers hostile to “cults” started meeting since the last decades of the past century. We have also documented, by publishing inter alia the excellent works by Japanese investigative journalist Fukuda Masumi, that these lawyers were not only motivated by greed and by the perspective of easy money to be made by suing “cults.” Most of them were Socialists and Communists and they wanted to target one specific new religion that had been successful in Japan with its anti-Communist campaigns, the Family Federation, then called the Unification Church.

I return now to Prime Minister Abe’s sad assassination. Immediately arrested on the scene, Yamagami, the killer, soon overtly confessed his murder to the local police. When Abe was officially declared dead, Yamagami was formally accused of murder. As more accusations against him were brought forth in the following months, as of March 30, 2023, and up to this day, the total charges against the self-confessed assassin reached the number of four. He risks also the death penalty, even if in similar previous cases it was commuted into life imprisonment.

One element is quite noteworthy here. The killer Yamagami has made clear that he had nothing against Abe’s political orientation, ideas, or party, and did not assassinate him for any reason directly or indirectly, openly or secretly, connected to politics. Yamagami said he had killed an innocent man and a prominent leader of this country, whether or not one is sympathetic to his political view and policies, only and manifestly out of his deep resentment and hate for the Unification Church/Family Federation.

He in fact underlined that he had been previously trying to kill Dr. Moon Hak Ja Han (한학자), the widow of Reverend Moon and the co-founder of the Unification Church, only to later decide to give up because of the difficulties in getting close enough to her. So, he turned to Abe, a politician known to be sympathetic to the Unification Church. Yamagami was never a member of the Unification Church, but his mother was and is. Yamagami claimed that because of her excessive donations to the Church her mother went bankrupt, and this condemned him and his siblings almost to starvation, pushing his brother to commit suicide and him to attempt it.

After more than two years from that murder, many shadows remain on the case. But the key element here is that, as a result, while the assassin still remains with no trial and sentence, the FF has been overloaded with accusations, as if it were the perpetrator rather than the victim. The FF is being punished, not the criminal. Abe paid a high price, the FF is paying a high price, but the villain was solely the assassin. No one else but him should be made accountable for that heinous crime. Yet, as I said, the contrary is happening.

The whole thing displays a twisted logic, that can be summed up into four main points.

First, let me repeat that the assassin was not and had never been a member of the Unification Church or the Family Federation.

Second, his mother declared bankruptcy in 2002. After her brother-in-law complained, two Church members returned in installments 50% of the donations.

Third, Abe was not a member of the Unification Church/Family Federation either, although many FF members undoubtedly supported him and voted for him in the elections. He did participate by remote to a 2021 event, and sent a message to another event in 2022, of the Universal Peace Federation, an NGO founded by the leaders of the Unification Church. But so did Donald Trump, two times president of the United States, former European Commission presidents José Manuel Barroso and Romano Prodi, and dozens of other politicians of all persuasions. I have attended myself similar events where I listened to the speeches and messages of politicians of different leanings.

Fourth, why did the assassin kill Abe in 2022 when his mother declared bankruptcy twenty years before, in 2002? While I am certainly not blaming the anti-cult movement for the crime, “The Journal of CESNUR” has also documented that in the last years before the assassination Yamagami started participating in anti-cult Internet fora, which may have excited his feeble mind.

In the face of these elements, the least one can say is that this is a cloudy situation.

Those four points makes it clear that Yamagami, the killer of Abe is, as some Western scholars have suggested, one of the most successful political assassins in history. His stated aim was to create trouble for and possibly destroy the Family Federation. While many political assassinations backfire, and the criminals do not achieve their aims, so far Yamagami is being remarkably successful. Of course, he is successful because he clouds his crime with several lies.

I am of course not the prosecutor of Yamagami, not intend to be. I do not want to anticipate any court of law of this honorable country. I just try to do my work as an observer and a reporter. I just used the word “lies” because Yamagami’s claim on the supposed guilt of the FF is evidently false, a fact that can be demonstrated in many ways. For the sake of our argument today, and above all for the sake of truth, I want to indulge for a moment now in the mental mechanisms that brought the assassin to his wrong conclusion.

As said, the assassin committed his criminal act having decided that the Unification Church and even politicians who showed some sympathy to it needed to be punished because the church’s doctrines and teachings led his mother to a specific behavior he condemns. Basically, the assassin thinks that the Unification Church/Family Federation is an evil “cult.”

It is certainly true that for the international anti-cult movement that defined the word, the Unification Church was the quintessential and even stereotypical “cult.” Definitions of “cults” we may find in dictionaries do not apply to the FF. But this is, while interesting, politically irrelevant since the anti-cult movement has hijacked the world, including in Japan, and has imposed its own definition and its list of “cults” to the media.

In the West, the academia, courts of law, and at least some quality media have abandoned this derogatory and discriminatory terminology. This does not seem to be the case in Japan. On December 13, 2022, radically modifying its previous case law, in the decision “Tonchev and Others v. Bulgaria,” the European Court of Human Rights stated that governments, national and local, cannot use the word “cult” and parallel expressions in other languages to stigmatize religious minorities in official documents and campaigns, since this is inherently discriminatory and may even generate violence. Again, as far as I know, this decision that created great international interest has rarely been discussed or even mentioned in Japan. In this country, it seems that the authorities continue on the dangerous path of stigmatizing religious minorities by calling them “cults” or “anti-social” organizations.

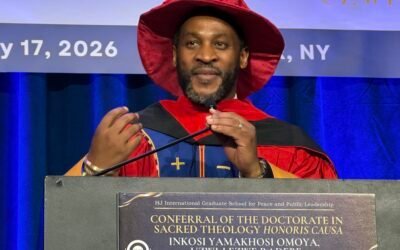

Marco Respinti is an Italian professional journalist, member of the International Federation of Journalists (IFJ), author, translator, and lecturer. He has contributed and contributes to several journals and magazines both in print and online, both in Italy and abroad. Author of books and chapter in books, he has translated and/or edited works by, among others, Edmund Burke, Charles Dickens, T.S. Eliot, Russell Kirk, J.R.R. Tolkien, Régine Pernoud and Gustave Thibon. A Senior fellow at the Russell Kirk Center for Cultural Renewal (a non-partisan, non-profit U.S. educational organization based in Mecosta, Michigan), he is also a founding member as well as a member of the Advisory Council of the Center for European Renewal (a non-profit, non-partisan pan-European educational organization based in The Hague, The Netherlands). A member of the Advisory Council of the European Federation for Freedom of Belief, in December 2022, the Universal Peace Federation bestowed on him, among others, the title of Ambassador of Peace. From February 2018 to December 2022, he has been the Editor-in-Chief of International Family News. He serves as Director-in-Charge of the academic publication The Journal of CESNUR and Bitter Winter: A Magazine on Religious Liberty and Human Rights.