Jack Donnelly’s theory of human rights may be used as a tool to evidence how Tai Ji Men was the victim of an extraordinary injustice.

by Michele Olzi*

*Introduction to the international webinar “The Tai Ji Men Case: Human Rights vs. Human Wrongs,” co-organized by CESNUR and Human Rights Without Frontiers on December 10, 2024, UN Human Rights Day.

Both the ICCPR (International Covenant on Civil and Political Rights) and the International Covenant on Economic, Social and Cultural Rights (ICESCR) refer to a fundamental and universal human right, that is, the right to freedom of thought, conscience, religion, or belief.

Often referred to as “freedom of religion or belief” (FoRB), it is articulated in both the ICCPR and ICESCR, respectively in article 18 and in article 2. I would like to quote some excerpts from both Covenants. Article 18 ICCPR reads: “Everyone shall have the right to freedom of thought, conscience, and religion. This right shall include freedom to have or to adopt a religion or belief of his choice, and freedom, either individually or in community with other and in public or private, to manifest his religion or belief in worship, observance, practice and teaching… Freedom to manifest one’s religion or belief may be subject only to such limitations as are prescribed by law and are necessary to protect public safety, order, health, or morals or the fundamental rights and freedoms of the others.”

Article 2 ICESCR reads: “[…] the rights enunciated in the present Covenant will be exercised without discrimination of any kind as to race, color, sex, language, religion, political or other opinion, national or social origin, property, birth or other status.”

Both excerpts show one crucial component in the endorsement of collective and individual freedom, namely the “right” itself. In the field of Political Theory, the debate over the notion of “right” focuses on its different dimensions and meanings. According to political scientist Jack Donnelly, this notion has both moral and political features. These latter connotations are well represented by the two concepts of rectitude (which might be related to “something being right, or wrong”) and entitlement (which might be related to “someone having [a] right”). “Denying you something that it would be right for you to enjoy in a just world—writes Donnelly—is very different from denying you something […] that you have a right to enjoy.”

Both conceptions concern the relations between people. If we conceive human rights as a “complex and contested social practice that organizes relations, between individuals, society and the state,” then we understand how several implications emerge from this definition. More specifically, we understand that “having a right” means almost nothing—even in modern democracies—if it is not enforced or respected by fellow citizens. At the same time, “being right” might have nothing to do with the respect of human rights within a specific state or under a specific government. To understand how both features can coexist, we need to focus on a specific aspect of this dynamic. As Donnelly argues, human rights regulate relations between individuals and the state.

As citizens, individuals are entitled to affirm their rights. Rights are not just mere ideals, abstract concepts, or values. Values need to be translated in active policies with rigorous standards of political life. In other words, quoting Donnelly again: “Human rights are not just abstract values such as liberty, equality, and security. They are rights, entitlements that ground particular social practices to realize those values. Human rights claims express not mere aspirations, suggestions, requests, or laudable ideas but rights-based demands. And in contrast to other grounds on which goods, services, and opportunities might be demanded—for example, justice, utility, divine donation, or contract—human rights are owed to every human being, as a human being.”

This latter passage introduces two crucial aspects of human rights: their origin and their universality. In Political Theory, since the introduction of Thomas Hobbes’ considerations on natural and civil laws, scholars have discussed the reason why people could/should live together. The question that Donnelly poses here is: “What in (our) ‘nature’ gives us ‘natural rights’?’’ Needs and fear are frequent answers to the question. However, not all political imaginaries and scenarios lie on such principles. Therefore, human rights are not respected—in the two-fold conception previously presented—only because governments are feared, or because protection is needed. According to Donnelly: “A closer examination suggests that human rights rest on our moral nature. They are grounded not in a descriptive account of psycho-biological needs but in a prescriptive account of human possibility. We have human rights not to the requisites for health but to those things ‘needed’ for a life worthy of a human being.”

According to the political scientist, the core of the human nature is characterized by a moral feature. Given the fact that this innermost component grounds human rights, we can say that these latter are closer to a sort of “social project.” Human rights are both an “utopian ideal” and a “realistic practice for implementing that ideal.” The hybrid nature of human rights involves both the limits and potentiality of human society. According to Donnelly, “Human rights constitute individuals as a particular kind of political subject: free and equal rights-bearing citizens.” Therefore, the UN Two Covenants—together with the Universal Declaration of Human Rights—marked a crucial achievement in the process that has been characterized by and through this notion of human rights.

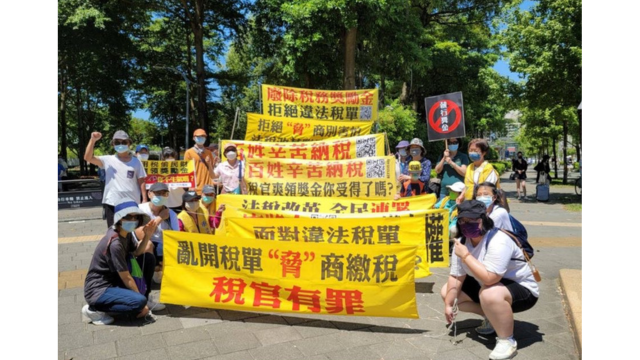

However, much more needs to be done. The Tai Ji Men case is, in this respect, emblematic. Taiwan is not a member state of the United Nations, yet it incorporated the Two Covenants into its domestic law in 2009. The financial persecution by the National Taxation Bureau (NTB) against Tai Ji Men is a blatant violation of the Covenants. Notwithstanding the 2007 decision of the Supreme Court, which declared Tai Ji Men defendants innocent of all charges, including tax evasion, the National Taxation Bureau maintained its unjust tax bills. Finally, after protracted litigation it corrected all of them to zero, except the one for the year 1992, based on a legal technicality.

Because of this fabricated tax bill, another violation of the Covenants occurred in 2020, when—based on the taxes allegedly due for 1992—Tai Ji Men’s sacred land in Miaoli was seized, unsuccessfully auctioned off, and nationalized. Finally, as recently as August 2, 2024, the Two Covenants were violated again when the Taichung High Administrative Court ruled against Tai Ji Men and failed to rectify the injustice vested on them.

The Tai Ji Men case is a blatant example of how freedom of religion or belief, solemnly affirmed by the UN Human Rights Covenants, continues to be violated even in democratic countries. The case calls for an urgent solution.

Michele Olzi is currently teaching assistant to the chair of Political Theory and to the course of Religion and Media at the University of Insubria (Varese and Como). His interests include political theory, collective imaginaries, history of ideas, history of religions, religion & media, new religious movements, “technognosticism,” hyper-real Religions, religions and politics. He is a member of the organizing and scientific committee of the annual conference of Foro di Studi Avanzati Gaetano Massa. He edits the online journal La Rosa di Paracelso.