The final session of the conference “Nation Building and Cultural Diversity in East Asia” at Vytautas Magnus University explored unsolved Taiwanese issues of freedom of religion or belief.

by Daniela Bovolenta

Is there freedom of religion in Taiwan? Many would say the answer is not difficult, as Taiwan is often presented, in contrast with Mainland China, as a beacon of human rights and religious liberty in East Asia.

Yet, the question is less obvious than it may seem, as evidenced by the final plenary session of the international conference “Nation Building and Cultural Diversity in East Asia: Challenges, Narratives, Perspectives,” held on October 18–19, 2024 at the prestigious Vytautas Magnus University in Kaunas, Lithuania. It was the fourth conference of the Baltic Alliance for Asian Studies, and the first held after COVID. Although Japan, South Korea, and Mainland China were also discussed, the conference had a special focus on Taiwan and was supplemented by a photographic exhibition about the island.

The last session was devoted to “New Religious Movements in Taiwan, During and After the Martial Law Period.” Massimo Introvigne, an Italian sociologist and the Managing Director of CESNUR, the Center for Studies on New Religions, opened the session with a paper on the repression of the large Chinese new religious movement Yiguandao during the Martial Law period in Taiwan. Severely persecuted in China during the Chairman Mao era, thousands of Yiguandao members escaped to Taiwan, hoping to find religious liberty there.

However, they were disappointed. The Kuomintang authorities regarded Yiguandao as a superstitious “cult” escaping the control of the government, banned it, launched a slander media campaign against its leaders falsely accusing them of sexual improprieties, and arrested thousands of members. However, Yiguandao continued to exist clandestinely and even grew, thanks to the protection of some Kuomintang politicians whom the movement supported in local elections, which were introduced in Taiwan well before political elections and the end of the Martial Law.

Introvigne then compared the authoritarian repression of Yiguandao and the post-authoritarian repression of Tai Ji Men. Obviously, the latter has been less severe: Yiguandao maintains that some of its leaders were killed during the White Terror, and certainly there were cases of massive arrests and torture. Physical violence, Introvigne said, is however not the only form of violence. Ultimately both the Yiguandao and the Tai Ji Men cases demonstrate the prevalence in Taiwan of the idea that spiritual movements are expected to actively support the powers that be, and are repressed if they fail to do so. Another element of similarity in the two cases was the use of media slander by prosecutors to create a climate of hostility against the movements they wanted to persecute.

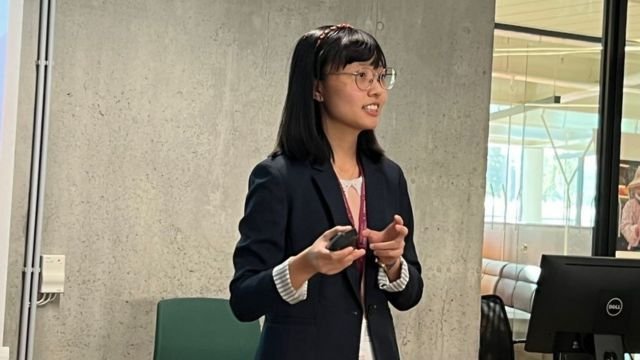

Yowting Shueng, a Ph.D. student at the Department of Religious Studies of National Chengchi University in Taipei, focused precisely on the use of the media as a tool for discrimination. Just as at the beginning of the Tai Ji Men case more than 400 media articles repeated the false arguments of the prosecutor, causing discrimination and harassment of the dizi (disciples), recently the Netflix documentary “In the Name of God” caused serious problems for the more than 4,000 members of the Christian Gospel Mission (CGM) in Taiwan.

The Taiwanese CGM, she said, is organized autonomously although it recognizes the theological authority of the Korean CGM, also known as Providence. In Korea, Providence’s leader has been sentenced to long jail terms in two sexual abuse cases (although the second is not concluded). Whatever the truth and the outcome of these cases in Korea, Shueng observed. Taiwanese CGM members are not accused of any crime, yet after the Netflix series their names were exposed, a media campaign followed, and some lost their jobs or were otherwise harassed.

Speaking via video from Italy, Rosita Šorytė, a former Lithuanian diplomat and a member of the scientific committee of FOB, the European Federation for Freedom of Belief, asked the question whether there is an anti-cult movement in Taiwan, similar to the ones existing in France or Japan. Indeed, European anti-cultists have lamented themselves that establishing solid anti-cult organizations has proven impossible in Taiwan. This is true, commented Šorytė, mentioning the failure of Prosecutor Hou Kuan-Jen, the man who created the Tai Ji Men case, when he tried to create a fake “association of victims.” However, she said that four comments should be added.

First, Taiwan shares with Mainland China the idea dating back to Imperial times that religious and spiritual groups are expected to actively support the political power and are punished if they are supposed not to do it. This is what happened to Tai Ji Men after the 1996 Presidential elections, when it was suspected not to have supported the Kuomintang candidate who was eventually elected. Second, Taiwan was not always a democracy. There was no real religious liberty during the Martial Law period, and the consequences of what happened then are still felt now. Third, the post-authoritarian transition to democracy in Taiwan was slow and difficult, as proved by the fact that as late as 1996 there was a politically motivated crackdown on religious and spiritual movements, which also created the Tai Ji Men case. Fourth, a tradition of hostility by several media to minority religious and spiritual movements continue, as evidenced by other papers in the session.

Liu Yin-Chun, a Tai Ji Men dizi with a degree in Slavic Studies, currently managing a bio-technology company in the Netherlands, presented the last paper of the session. In the first part, she described the achievements of Tai Ji Men, also known as “the Energy Family,” in spreading the teachings of an ancient menpai (similar to a “school”) of martial arts, Qigong, and self-cultivation, and at the same time promoting global initiatives centered on peace education and the emphasis on conscience.

In the second part, Liu summarized the Tai Ji Men case, based on the false argument that Tai Ji Men is a “cram school” with the consequence that the monetary offerings by dizi to their Shifu (Grand Master) were considered taxable tuition fees rather than non-taxable gifts. This argument was rejected by courts of law in Taiwan, up to the Supreme Court, but maintained by the National Taxation Bureau (NTB) to issue ill-founded tax bills. Finally, all the bills were corrected to zero, with the exception of the one for the year 1992, based on a technicality. The 1992 bill was the basis in 2020 for seizing, unsuccessfully auctioning off, and nationalizing sacred land where Tai Ji Men intended to build a self-cultivation center and educational institutions. The matter was lived as a painful injustice by Tai Ji Men dizi in Taiwan and internationally.

Liu offered a legal and economical analysis of the Tai Ji Men case. Legally, it was built from its very beginning by Prosecutor Hou on massive violations of both domestic law and the universal principles of international law. Economically, it did not only damage Tai Ji Men. Both by justifying tax abuse and making reforms more difficult and by tarnishing the international image of Taiwan it created economic damages affecting all Taiwanese.

During the vibrant Q&A session, the speakers confirmed that the level of religious discrimination in present-day Taiwanese society cannot be compared either to Mainland China or to the years of the White Terror and the Martial Law in Taiwan. Yet, as the Tai Ji Men case and certain attitudes by the media demonstrate, not all problems are solved, and efforts are still needed to fully align Taiwan with the international standards of freedom of religion or belief.