The great academic debate on vampires of the eighteenth century was restarted by some nineteenth-century demonologists—but it was soon marginalized.

by Massimo Introvigne*

*A paper presented at the Occult Convention 2024, organized by the Società dello Zolfo, Parma, September 7, 2024

Article 5 of 5. Read article 1, article 2, article 3, and article 4.

After Calmet and after the pronouncements of state and church, of Maria Theresa and Benedict XIV, the skeptic party that did not believe in the existence of vampires quietly established itself as dominant. In the nineteenth century, however, there was a revival, on a more modest scale, of the eighteenth-century discussion, due to two successive events, which led to a renewed belief in the direct action of the devil in historical events. The first was the French Revolution, which many considered impossible to explain by merely human causes. The second was the equally surprising rise of Spiritualism.

Nineteenth-century demonology started with the voluminous work by German Protestant theologian converted to Catholicism Johann Joseph von Görres, “Die Christliche Mystik.” Görres distinguishes between three types of “mysticism”: divine, natural, and diabolic. Vampirism was discussed in the context of “natural mysticism” with reference to a “vital principle,” which corresponded, as had happened for the eighteenth-century neo-Paracelsians, to the nutritive or “vegetative” soul. In vampires, Görres argued, there is no longer a “human life,” but there is a “vegetative life” that circulates in the blood and prevents corruption of the body. Vampires do not come out of the graves or suck the blood of the living, but their “vegetative life” creates a negative energy that escapes from the grave and causes illness and hallucinations in the living.

Curiously, while Görres is sometimes presented today as too credulous, a certain French demonology that flourished after the mid-nineteenth century criticized him on the contrary for being too skeptical. It accused him of having sought natural or dangerously esoteric explanations of what was instead the work of the devil.

The two leading French demonologists of this period were Marquis Jules Eudes de Mirville and diplomat Henri-Roger Gougenot des Mousseaux, the latter remembered today mainly as an anti-Jewish theorist. For both, vampires are corpses that come out of the graves and kill, and they do so because they are possessed by the devil. Why does the devil do this? Because his nature is murderous. “Blood, blood!” wrote Gougenot, “This is their best cry: all devils are vampires, and why? Because they are the Homicidal Spirits of the abyss.”

In the twentieth century, there were no longer scholars of theology or academic esotericism who believed in vampires as undead human beings coming out of the graves and sucking the blood of the living. What persisted, and even grew, was the belief in the existence of the psychic vampire, which is, however, a different figure.

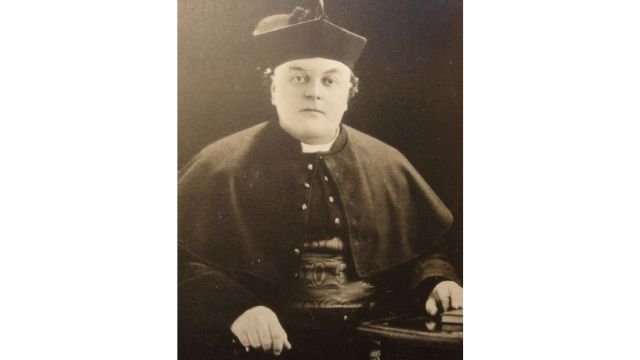

Those who still believed in blood-sucking undead were fringe figures such as Montague Summers who, after passages in the Anglican and Catholic Churches, continued a career in the world of the “wandering bishops” (who claim a more or less real apostolic succession from Catholic or Orthodox bishops but are not in communion with either Rome or the canonical Orthodox Churches; in general, they also have a very limited number of followers).

Summers had no doubts about the real existence of vampires, undead who really came out of their graves by the work of the devil. He only left open the question whether the devil animated the dead as if they were dummies, or whether the activities of the deceased during life had anything to do with their becoming vampires after death.

In 1948 with Montague Summers disappeared the last intellectual—however marginal and controversial —willing to argue in favor of the existence of vampires as deceased but “undead” human beings. As already mentioned, many—and certainly many esoteric orders—think that psychic vampires exist who drain others of their energy, but they are living rather than deceased human beings. Various religions and movements believe that there are evil demons acting as incubi and succubi, but they are not human. And certainly sociologists, not to mention police officers, know that there are “vampires” who influenced by literature try to drink their partner’s blood—usually before discovering that it is emetic—or even criminals who are cannibals or drinkers of their victims’ blood or both. But these too are living human beings, not dead coming out of the graves.

Many are familiar with Marx’s quote that history repeats itself the first time as tragedy and the second time as farce. Today there remain vampire stories that seem more farce than tragedy. For example, in the world of fundamentalist Christians who denounce the “danger of the cults,” a curious character is the American William Schnoebelen. After having been part of the “wandering bishops” underworld, an adept of various esoteric orders, and a Mormon, he now presents himself as a Christian fundamentalist. He proposes sensational revelations that there are vampires in “cults” such as the Ordo Templi Orientis (OTO). He himself claims to be a vampire converted by Jesus. A slogan of his campaigns reads, “If Schnoebelen, crazed by blood lust and headed for murder, could be changed by Jesus Christ, ANYONE can!”

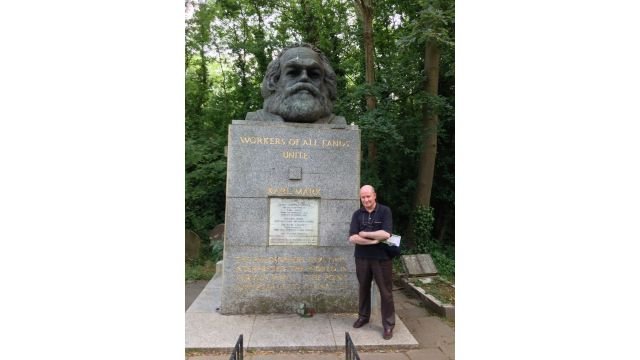

Another story that has a flavor of farce—but delighted London tabloids for decades—is the one that there is a vampire in the Highgate Cemetery, the very one where Marx is buried. The story began in 1968 and quickly became a feud between two colorful characters from London’s occult underworld, Sean Manchester (a “wandering bishop” and self-proclaimed disciple of Summers) and David Farrant (a candidate for the British Parliament in 1978 for his Wicca Workers Party, which called for freedom to walk around naked in the streets and state brothels at subsidized rates). Each claimed to know the truth about the Highgate vampire and that his rival was a waffler and a fraud. Farrant ended up in prison when corpses buried in Highgate were pulled from the graves and beheaded, although he denied all charges. After his death in 2019, interest in the Highgate vampire greatly diminished.

Do vampires exist? Perhaps to this question it would be more romantic and amusing to answer “yes,” but an objective examination of centuries of discussions, which were more serious than one might think, induces us to conclude that no, there are no deceased “undead” humans in the real world who suck the blood of the living. However, vampires do exist in the world of imagination, which has its own consistency and “reality” and certainly determines social effects. Studying the mythology of the undead may also be useful for understanding the discussions on “psychic vampires” and for exploring the multiple dimensions of the human aspiration for immortality.

Massimo Introvigne (born June 14, 1955 in Rome) is an Italian sociologist of religions. He is the founder and managing director of the Center for Studies on New Religions (CESNUR), an international network of scholars who study new religious movements. Introvigne is the author of some 70 books and more than 100 articles in the field of sociology of religion. He was the main author of the Enciclopedia delle religioni in Italia (Encyclopedia of Religions in Italy). He is a member of the editorial board for the Interdisciplinary Journal of Research on Religion and of the executive board of University of California Press’ Nova Religio. From January 5 to December 31, 2011, he has served as the “Representative on combating racism, xenophobia and discrimination, with a special focus on discrimination against Christians and members of other religions” of the Organization for Security and Co-operation in Europe (OSCE). From 2012 to 2015 he served as chairperson of the Observatory of Religious Liberty, instituted by the Italian Ministry of Foreign Affairs in order to monitor problems of religious liberty on a worldwide scale.