In the seventeenth century, the German “nachzehrer” and the Greek “vrykolakas” were precursors of vampires that started interesting theologians and scholars.

by Massimo Introvigne*

*A paper presented at the Occult Convention 2024, organized by the Società dello Zolfo, Parma, September 7, 2024

Article 1 of 5.

The word “vampire” today evokes mostly the vampires of literature, film, and comics. But the literary vampire came into being, in the late eighteenth and early nineteenth centuries, because there was an ongoing discussion, both theological and properly “esoteric” (although this word was not yet in use), about the existence of vampires. In this series we will not talk about the literary vampire, who is almost always aristocratic, handsome, seductive, and sexy. The vampire whose possible existence was discussed between the seventeenth and nineteenth centuries was usually an undead peasant, rather ugly and smelly.

We will not even discuss the question of the origins of belief in vampires—with hypotheses locating them in Siberia, India, China, and Romani folklore—because the theological-esoteric discussion we address has never actually dealt with it.

The prehistory of our discussion is represented by the debate, beginning in Germany in the sixteenth century, whether there was such a thing as the “nachzehrer,” which was strictly speaking not a vampire but one of its precursors. He was a dead man (more rarely a woman) who chewed in his grave. He chewed on the veil, the shroud, the clothes but might also try to bite his own hands and arms. This activity might seem harmless—and even destined to remain unknown forever, at least if the graves were tightly closed—but it was not.

The chewing of the “nachzehrer,” according to popular belief, in fact caused a mysterious draining of energy among those who lived some distance from the grave, who might even die. Moreover, eventually, through the chewing, the “nachzehrer” became stronger, emerged from the grave, and went in search of other things to chew, until he was so strong that he attacked the living. In this case, in other words, he had become a vampire, although the term was not yet used.

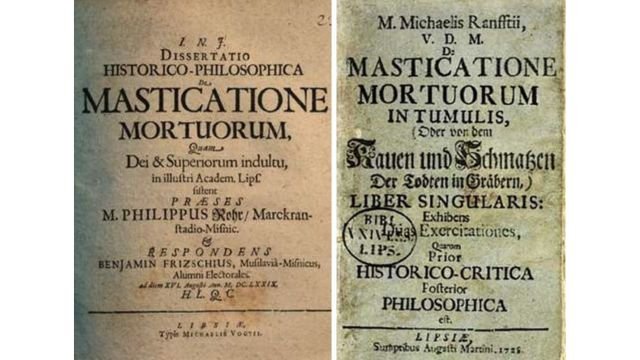

Although even Martin Luther already mentioned the “nachzehrer,” the decisive work for the theological-esoteric debate about its existence was the “Dissertatio historico-philosophica de masticatione mortuorum” delivered at the University of Leipzig by Protestant theologian Philip Rohr and immediately printed in the year 1679. Rohr took for granted that the “nachzehrer” existed. He referred to earlier texts and discarded two hypotheses advanced by seventeenth-century authors: that some deceased people retain an “unknown faculty” that operates after death and that their bodies are possessed by the biblical demonic serpent Azazel. Rohr concluded that the body of the “nachzehrer” was indeed possessed, but by the devil.

But why would the devil waste his time creating these phenomena? Rohr answered that the devil does not attack the dead but the living. He wants to cause terror and confusion among those living near the graves, and also quarrels because it will be said that the “nachzehrer” has become such because of past sins. For Rohr this was generally a slander created by the devil, especially against virtuous women whose chastity some began to doubt after hearing them “chewing” in their graves.

Rohr was answered, also in Leipzig, by another Protestant theologian, Michael Ranft, with his “Dissertatio historico-critica de masticatione mortuorum in tumulis” of 1725, which had several later editions in which he used the word “vampyr.” For Ranft, the devil had nothing to do with the “nachzehrer.” An advocate of the notion of a “natural magic,” neither divine nor devilish, Ranft asserted that in addition to the soul and the body there is in humans a “vegetative soul” that can continue to exist attached to the corpse for some time. One sign that the vegetative soul is still alive in the male corpse is the intact and erect penis. The vegetative soul can also release negative energy against people the deceased hated in life, which explains why they die.

In the seventeenth century, while “nachzehrer” were discussed in Germany, “vrykolakas” were discussed in Greece. The first work of reference was Leone Allacci’s “De quorundam Graecorum opinationibus” (1645). According to Allacci, “the vrykolakas is the body of a man of evil and immoral life, often that of someone who has been excommunicated by his bishop. Such bodies do not decompose after being buried like those of other dead people. Emerging from the grave, the vrykolakas goes to a house and, knocking on the door, calls out by name to one of the people living there. If the person answers, she is lost. She will certainly die the next day. But if she does not answer, she is saved. The vrykolakas, in fact, never calls twice.”

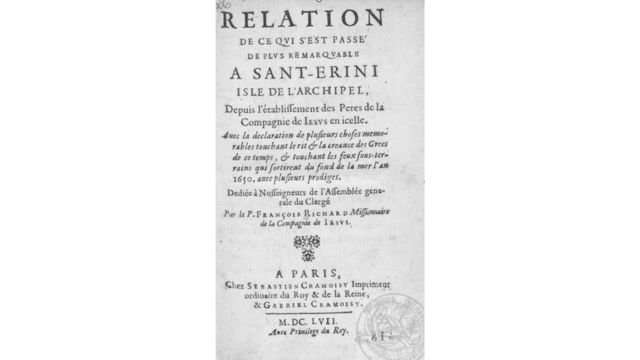

Allacci was not sure that the phenomenon of “vrykolakas” was real; indeed, he believed that it might be mere hearsay. A few years after Allacci’s work, however, an account appeared in Paris by Jesuit François Richard, who had been a missionary to the Greek island of Santorini. For the Jesuit, the phenomenon of “vrykolakas” was absolutely real but it was not about the dead coming out of the tombs and walking around. It was the devil who either assumed their image or even possessed their bodies just as he possesses the living. For the Jesuit, the “vrykolakas” was simply “a special case of diabolic possession.”

In the eighteenth century, treatises on “nachzehrer” and “vrykolakas” began to use the word “vampire” because vampires were being dealt with by the Church, the gazettes and even the police. We will examine this extraordinary phenomenon in the next installment of this series.

Massimo Introvigne (born June 14, 1955 in Rome) is an Italian sociologist of religions. He is the founder and managing director of the Center for Studies on New Religions (CESNUR), an international network of scholars who study new religious movements. Introvigne is the author of some 70 books and more than 100 articles in the field of sociology of religion. He was the main author of the Enciclopedia delle religioni in Italia (Encyclopedia of Religions in Italy). He is a member of the editorial board for the Interdisciplinary Journal of Research on Religion and of the executive board of University of California Press’ Nova Religio. From January 5 to December 31, 2011, he has served as the “Representative on combating racism, xenophobia and discrimination, with a special focus on discrimination against Christians and members of other religions” of the Organization for Security and Co-operation in Europe (OSCE). From 2012 to 2015 he served as chairperson of the Observatory of Religious Liberty, instituted by the Italian Ministry of Foreign Affairs in order to monitor problems of religious liberty on a worldwide scale.