Denied by some art historians, the influence of the Theosophical Society (which in turn rejected his artistic theories as too complicated) remained crucial until the Dutch painter’s last days.

by Massimo Introvigne

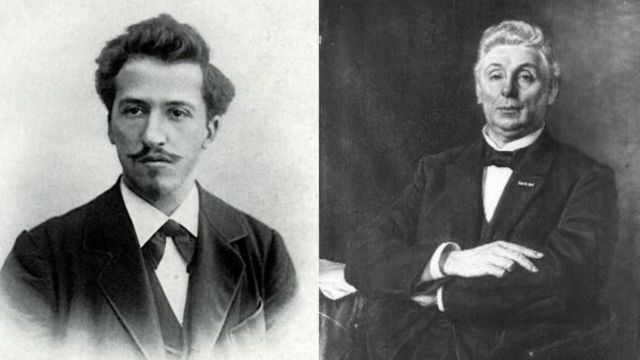

Piet Mondrian (1872–1944) joined the Theosophical Society on May 14, 1909. Early interpreters minimized its influence on the Dutch painter, with Yve-Alain Bois in 1990 claiming that “the Theosophical nonsense with which the artist’s mind was momentarily encumbered” quickly vanished from his work. However, Mondrian himself credited Theosophy for significantly shaping his art. In 1918, he told Theo van Doesburg (1883–1931) he “got everything from ‘The Secret Doctrine’” by Madame Helena Blavatsky (1831–1891). By 1921, Mondrian argued in a letter to Rudolf Steiner (1861–1925), that Neo-Plasticism was the “art of the foreseeable future for all true Anthroposophists and Theosophists.” When Steiner did not respond, Mondrian reiterated this view by writing to van Doesburg in 1922 that “it is Neo-Plasticism that exemplifies Theosophical art (in the true sense of the world).”

Mondrian’s theoretical writings are difficult to grasp without understanding their Theosophical roots. His first attempt to express his abstract art ideas was an article written for the Dutch Theosophical journal “Theosophia” in 1913–1914, but it was deemed too complex and rejected by the Theosophists, and got lost. However, two sketchbooks for the article compiled in Paris at that time survive. They reveal that Mondrian believed Theosophy could distill art into universal elements like colors and lines, capturing its essence beyond representation.

Dutch historian Carel Blotkamp suggested that Mondrian should be seen as a man of the Belle Époque. In 1919, Mondrian wrote from Paris about his excitement for the book “Comment on devient fée” by Joséphin Péladan (1858–1918). “You will find much of me in this work,” Mondrian wrote; “he takes inspiration from the same ancient sources (occult).” Although the book represented 19th-century occultism, which was seen as outdated by then, Mondrian still valued it.

The Dutch artist first encountered occultism and Theosophy while studying at Amsterdam’s Rijksacademie between 1892 and 1897. Among Mondrian’s classmates was Karel de Bazel (1864–1932), a prominent Dutch architect who joined the Theosophical Society in 1894 and co-founded its Vahana Lodge in Amsterdam in 1896. Fellow architects Johannes Lauweriks (1864–1932) and Hermanus Johannes Maria Walenkamp (1871–1933) were also members. From 1903, another notable Dutch architect, Michiel Brinkman (1873–1925), chaired the Rotterdam Theosophical Lodge.

Around 1900, Mondrian experienced a religious crisis, prompting him to leave his parents’ Calvinist Protestant faith and explore Theosophy and Edouard Schuré’s (1841–1929), book “The Great Initiates,” which he continued to study throughout his life.

In 1909, influenced by fellow painter Cornelis Spoor (1867–1928), Mondrian developed an interest in yoga and finally joined the Theosophical Society. Several of his paintings, such as “Devotion” (1908) and the triptych “Evolution” (1911), are linked to Theosophy, as Mondrian confirmed in his notebooks and letters. Scholar Robert P. Welsh (1932–2000) suggested that “Evolution” represents the three stages of Theosophical enlightenment.

When Mondrian went to Paris in 1912, he stayed at the French Theosophical Society’s headquarters before moving to his studio. In the Netherlands, he kept a portrait of Madame Blavatsky in his Laren studio.

Mondrian was already influenced by Theosophy before he met Mathieu Hubertus Josephus Schoenmaekers (1875–1944) around 1914 or 1915. Schoenmaekers, a former Catholic priest and Theosophist, developed his own “Christosophy” and significantly impacted Mondrian’s worldview, art, and the foundation of De Stijl in 1917. Schoenmaekers coined the term “Nieuwe Beelding” (Neo-Plasticism) in 1916. Initially, Mondrian was deeply influenced by Schoenmaekers, but by 1918, he viewed him negatively, believing any valuable ideas Schoenmaekers had were derived from Blavatsky. Mondrian argued that cosmic harmony, truth, and beauty could be represented by a vertical male line and a horizontal female color and background.

Theosophy influenced Mondrian’s development of Neo-Plasticism and his collaboration with, and eventual split from, van Doesburg in 1924–1925. Commonly, this split is linked to van Doesburg’s use of diagonal lines versus Mondrian’s horizontal and vertical preference. However, another factor was that van Doesburg, not a member of the Theosophical Society, began to criticize Mondrian’s “rigid” Theosophy and the shift of Neo-Plasticism into what he perceived as a religious movement.

Michel Seuphor (1901–1999) claimed that Mondrian’s beliefs evolved from Calvinism to Theosophy and ultimately to Neo-Plasticism, which replaced Theosophy as a comprehensive worldview. For Mondrian, especially after his 1930s debates with Dutch philosopher Louis Hoyack (1893–1967), Neo-Plasticism was a revolutionary project aimed at societal transformation. He believed Neo-Plastic painting eliminated old art forms to create new ones, and this philosophy could similarly reform state, Church, and family into simpler, better structures. His paintings were manifestos for this vision. Mondrian stated that “The rectangular plane of varying dimensions and colors visibly demonstrates that internationalism does not mean chaos ruled by monotony, but an ordered and clearly divided unity.”

Many Theosophists dismissed these utopian concepts and failed to grasp Mondrian’s art. He felt the leaders in the Theosophical Society were “always against my work.” Although his vision of global reform had similarities with Masonic ideas, he wrote in 1932 that his application to become a Freemason was ignored by the Dutch lodges.

Despite the painful rejections, Mondrian didn’t sever ties with Theosophy. Upon moving to London in 1938, he requested a transfer to the local Theosophical Society. Notably, his close friend in London was Winifred Nicholson (1893–1981), a Christian Scientist, whose metaphysical Christianity intrigued many Theosophists despite differing from Theosophy.

As Charmion von Wiegand (1896–1983), the American painter who was Mondrian’s closest associate and perhaps lover in the last years of his life, noted, after relocating to New York in 1940, Mondrian ceased his active involvement with the Theosophical Society, although remaining a member. She explained that he “had gone beyond organizations or groups […]. To him, they represented limitations, a division in the total unity he sought to achieve.” Nonetheless, von Wiegand asserted, he had not rejected Theosophy but had made it “implicit to his life.”

Mondrian considered himself an “old soul,” meaning he had gone through multiple reincarnations. Theosophy often states that old souls are misunderstood by their peers. Theosophists did not appreciate Mondrian’s Neo-Plasticism, expecting Theosophical art to feature specific symbols or “thought-forms”—the shapes and colors perceived by clairvoyants like Annie Besant (1847–1933) and Charles Webster Leadbeater (1854–1934). For many Theosophists, this was true Theosophical art, and Mondrian’s wasn’t. Mondrian, however, believed that pure Theosophical art was in fact Neo-Plasticism.

Massimo Introvigne (born June 14, 1955 in Rome) is an Italian sociologist of religions. He is the founder and managing director of the Center for Studies on New Religions (CESNUR), an international network of scholars who study new religious movements. Introvigne is the author of some 70 books and more than 100 articles in the field of sociology of religion. He was the main author of the Enciclopedia delle religioni in Italia (Encyclopedia of Religions in Italy). He is a member of the editorial board for the Interdisciplinary Journal of Research on Religion and of the executive board of University of California Press’ Nova Religio. From January 5 to December 31, 2011, he has served as the “Representative on combating racism, xenophobia and discrimination, with a special focus on discrimination against Christians and members of other religions” of the Organization for Security and Co-operation in Europe (OSCE). From 2012 to 2015 he served as chairperson of the Observatory of Religious Liberty, instituted by the Italian Ministry of Foreign Affairs in order to monitor problems of religious liberty on a worldwide scale.