The strong experiences of the Australian artist with the Theosophical Masters and her involvement in the Leadbeater case led her to spend twenty years in a psychiatric hospital.

by Massimo Introvigne

Theosophy had a strong influence on several leading modern artists. Many of them, including Piet Mondrian (1872–1944), who remained a member of the Theosophical Society until his death, were criticized for their involvement with a movement that art historians rarely understood and often simply dismissed as a “cult.”

For some, the Theosophical passage and the societal criticism of Theosophy had tragic consequences. This was the case of one of the leading Australian artists, Florence Fuller (1867–1946).

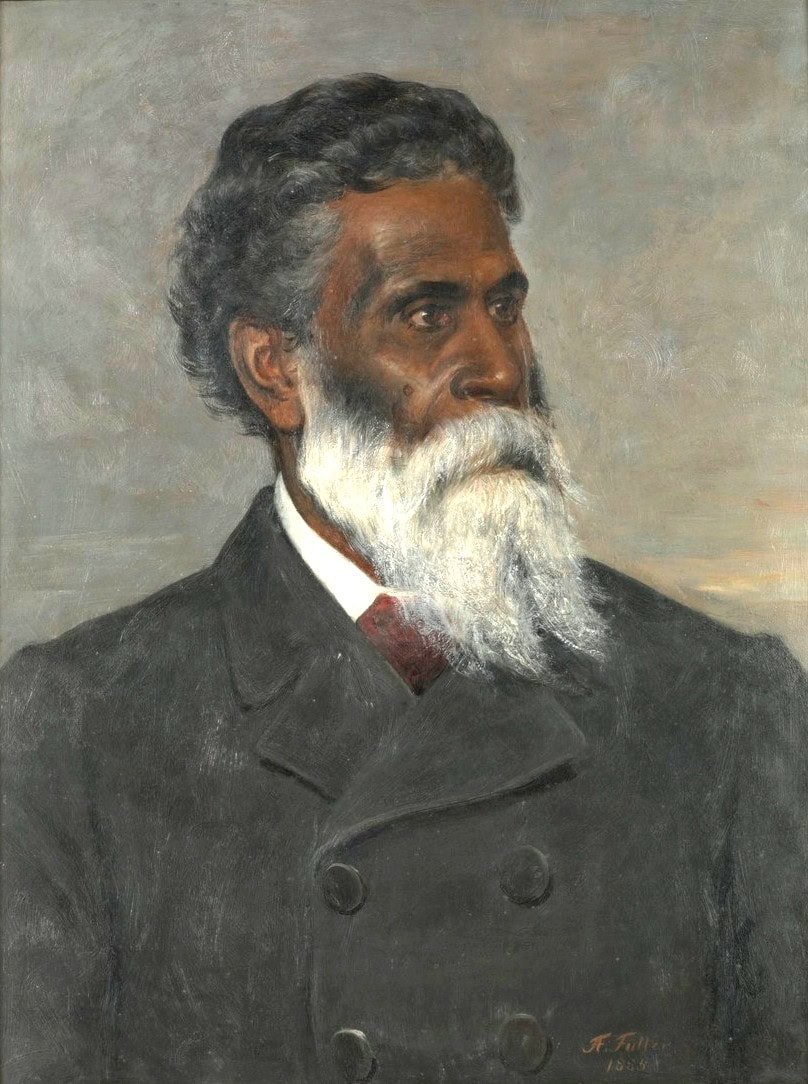

As a teenager artist in Australia, Fuller was considered a child prodigy. Her fame as a portraitist was established when, at the age of 17, she painted a famous depiction of the Aboriginal chief William Barak (1824–1903). She left Australia in 1892 to South Africa, Paris, and London. Her work was hailed by critics and exhibited at the Paris Salon and the Royal Academy. She returned to Australia in 1904, at age 37.

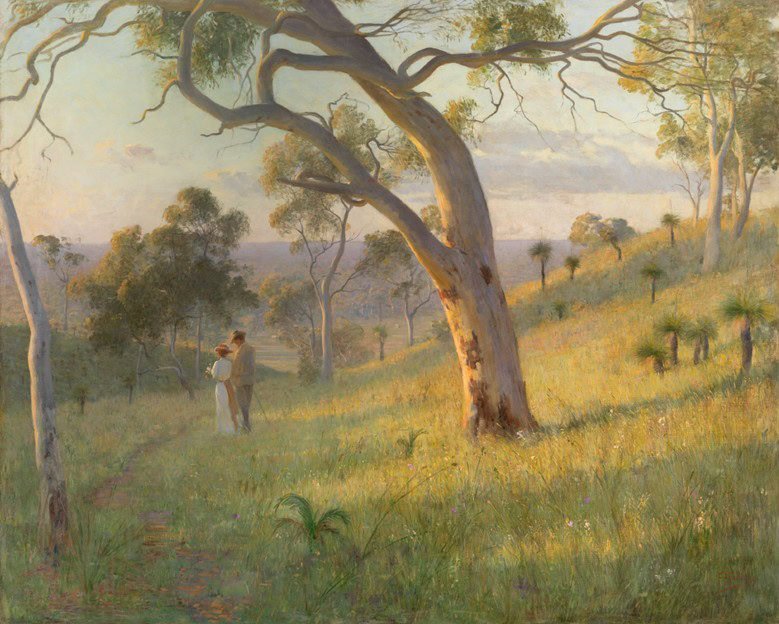

In 1905, Fuller painted “A Golden Hour,” now housed in the National Gallery of Australia in Canberra and considered one of the country’s national masterpieces. But in the same year, 1905, as the press celebrated her triumph, Fuller became an associate of Charles Webster Leadbeater (1854–1934), the leader of the Theosophical Society who had taken up residence in Australia and decided to devote her life to Theosophy.

She formally became a member of the Theosophical Society on May 29, 1905. Fuller might have been unaware of rumors of child sexual abuse surrounding Leadbeater in various countries, which led him to resign from the Theosophical Society in the following year 1906, although he was reinstated in 1908.

Fuller, a well-known artist in Australia at the time, assumed increasing responsibilities within the Australian and international Theosophical Society, and in 1907 moved to the Society’s world headquarters in Adyar, where she painted her portraits of Theosophy’s co-founder Madame Helena Blavatsky (1831–1891) and the then President of the Theosophical Society, Annie Besant (1847–1933).

In Adyar, Fuller became involved in the case of Jiddu Krishnamurti (1895–1986), a young Indian in whom Leadbeater and the Theosophical Society saw the vehicle of the “World Teacher.” Fuller imparted art lessons to Krishnamurti, and Leadbeater “saw” through clairvoyance that the artist and the young Indian, who will eventually publicly renounce his role as messiah, had already known each other in past lives.

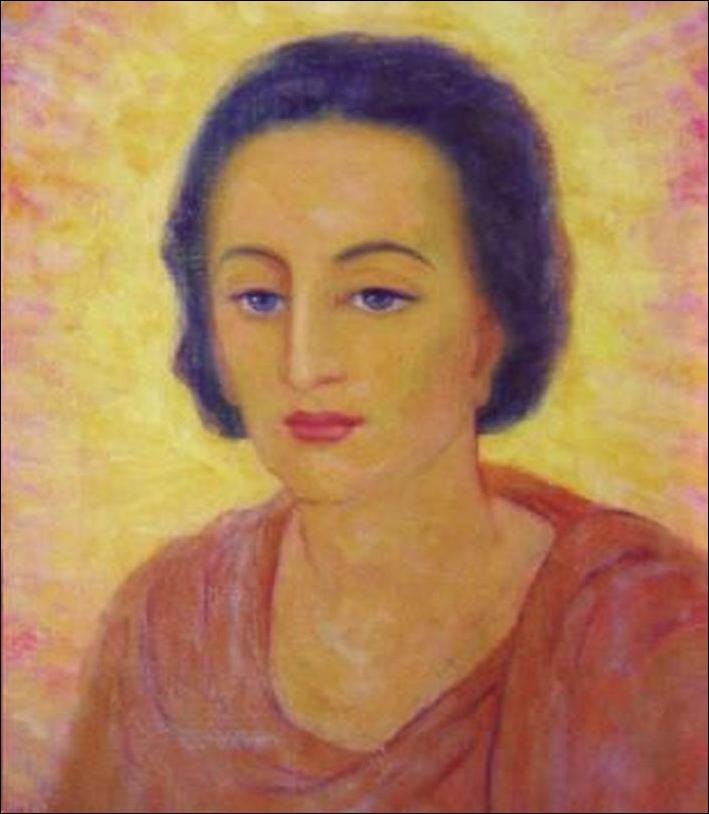

The Theosophical Society claims to be led by the Masters, figures who have acquired supernatural powers but remain on earth to help humans. Between 1908 and 1911 in Adyar Fuller was reportedly allowed to see the Masters herself and to paint them. These portraits remain secret to this day, except for that of Master Buddha, which was published in 1949 by an Australian Theosophical magazine.

Fuller described her personal encounter with the Masters as shocking and never totally recovered from the strong emotions of these years. She returned to Australia with Leadbeater in 1916. But she was no longer the popular Australian artist of the previous decade. The now public accusations of pedophilia against Leadbeater and the Krishnamurti affair contributed to her exclusion from respectable artistic circles and finally to her being considered insane.

In 1927, at age sixty, she was committed to Sydney’s Tarban Creek Lunatic Asylum. Fuller spent the last twenty years of her life in the psychiatric asylum, later known as the Gladesville Mental Hospital, where she died on July 17, 1946.

For almost eighty years, her name was more or less erased from Australian art history. She was rediscovered by Australian art historian Joan Kerr (1938–2004), and has now recovered her well-deserved status as a leading Australian painter. There is, however, a risk that Fuller is celebrated as an artist who achieved greatness “notwithstanding” her deep involvement in Theosophy. In fact, her artistic experience is inseparable from her Theosophical passage.

Massimo Introvigne (born June 14, 1955 in Rome) is an Italian sociologist of religions. He is the founder and managing director of the Center for Studies on New Religions (CESNUR), an international network of scholars who study new religious movements. Introvigne is the author of some 70 books and more than 100 articles in the field of sociology of religion. He was the main author of the Enciclopedia delle religioni in Italia (Encyclopedia of Religions in Italy). He is a member of the editorial board for the Interdisciplinary Journal of Research on Religion and of the executive board of University of California Press’ Nova Religio. From January 5 to December 31, 2011, he has served as the “Representative on combating racism, xenophobia and discrimination, with a special focus on discrimination against Christians and members of other religions” of the Organization for Security and Co-operation in Europe (OSCE). From 2012 to 2015 he served as chairperson of the Observatory of Religious Liberty, instituted by the Italian Ministry of Foreign Affairs in order to monitor problems of religious liberty on a worldwide scale.