Basically, anti-cultists and deprogrammers regarded as a “cult” any group that had as members children of parents willing to pay for deprogramming them.

by Anson D. Shupe (†) and Susan E. Darnell

Article 6 of 10. Read article 1, article 2, article 3, article 4, and article 5.

It is now known that when K.T., mother of three United Pentecostal sons for whom she sought deprogrammings, contacted CAN, neither the ultimate chief deprogrammer (“Bible-based expert”) Rick Ross nor anyone at CAN had ever heard of the Tabernacle Life Church or its parent body, the United Pentecostal Church International. This turned out to be a matter of irrelevance since CAN cast an enormously wide net to monitor possible “cults” and in entrepreneurial fashion assumed most groups inquired about were ones justifying “interventions” for families. The array of alleged “cults” expanded exponentially as the ACM and CAN continued into the 1990s. J. Gordon Melton, director of the Institute for the Study of American Religion, estimates that while the ACM was mostly concerned with about fifteen NRM—and of those, only five consistently over the year—as many as 75 to 100 received some attention (J. Gordon Melton, “Encyclopedic Handbook of Cults in America,” New York: Garland Press, 1986, 4–5).

In fact, the array demonstrated an increasing inclusiveness over the years. As one-time CAN associate Garry Scarff told two journalists in a post-Jonestown interview, trying to draw an analogy between the Unification Church and the Peoples Temple for suicide potential: “Whenever you’re dealing with religious categories like resurrection and birth, you begin to blur categories between life and death” (J. Carroll and B. Baker, “Suicide Training in the Moon Cult,” “New West,” January 29, 1979, 68). Such reasoning expanded considerably the number of groups of which to keep track. It bred distrust and guaranteed a growth industry of anticultists in the American religious marketplace. Traditional groups, such as the Christian Scientists and Mormons, over which evangelical counter-cult watchers had fretted for years, were of course invited to sit at the secular anticultists’ table of lists. So were variations of the Buddhist, Islamic, and Hindu world religions.

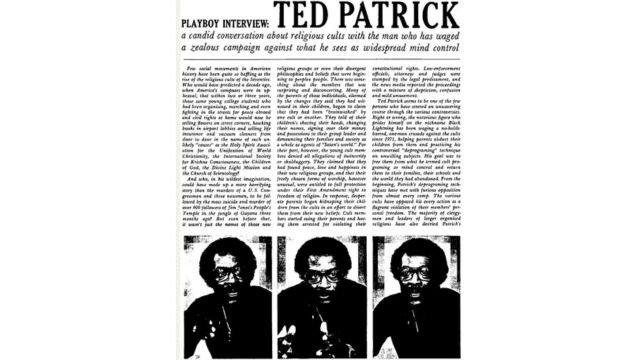

The game of identifying cults took on the nature of a binge, and at times ranged from the silly to the absurd. Momentum only increased from the 1970s into the 1990s. For example, taking his own home-spun wisdom to heart (i.e., “The Bible will drive you crazy if you take it literally”), deprogrammer Ted Patrick went on in a free-wheeling “Playboy” interview to claim that evangelist Ruth Carter Stapleton, president Jimmy Carter’s sister, was “one of the biggest cult leaders in the nation,” albeit a “good cult leader.” The Rev. Billy Graham was thrown in for good measure.

The net kept widening. Observed two sociologists: “At the end of the decade of the 1970s there were even indications that the ACM might take on television evangelists as well” (Anson D. Shupe, Jr. and David G. Bromley, “The New Vigilantes: Deprogrammers. Anti-Cultists and the New Religions,” Beverly Hills, CA: Sage, 1980, 115). Then came an alleged satanic underground network, and even quasi-religious corporations, such as Amway and Mary Kay, were accused of exhibiting cultic tendencies.

There seemed to have been an unspoken agreement among ACM participants, exemplified by CAN, to wit: “I’ll consider your group a cult if you’ll do the same for mine.” Deprogrammers’ parallel understanding seemed to be: “Any group referred to us, or disturbing to someone, requires intervention.” The result was an open season on not just NRMs but on any organization that smacked of enthusiastically accepted discipline, self-mastery, self-improvement, self-refection, and deeply held spiritual beliefs.

But the net widened still. By the mid-1990s, the high point of CAN, files were kept on a total of 1505 groups: from Amway, the Amish, and the Anti-Reformation League; to chiropractic, Roman Catholics, and Campus Crusade for Christ; from the makers of the board game Dungeons and Dragons to the Democratic Workers Party; to the First Baptist Church of Hammond, Indiana (America’s largest Protestant congregation) and the Full Gospel Business Men’s Fellowship International to the San Francisco rock band The Grateful Dead; on to the Inter-Varsity Christian Fellowship and the International Workers Party; to Klanwatch, the Ku Klux Klan, Lutherans, Mormons, Shirley MacLaine and the National Association of Evangelicals; on to the Oklahoma City bombings and Opus Dei; then to the Order of the Solar Temple, Protestants, Peoples Temple, Promise Keepers, and Jim/Tammy Faye Bakker’s’ PTL Club; to the Rockford Institute, the Rutherford Institute, and the Rajneeshees; to Soka Gakkai, Scientology, and Santeria; to “Teen” magazine, Transcendental Meditation, and the charismatic Toronto Blessing; to Urantia and the United Pentecostal Church; from the Worldwide Church of God and the Wycliffe Bible Society to Women Aglow and Youth for Christ.

If, as religious historian Philip Jenkins argues eloquently in “Mystics and Messiahs: Cults and New Religions in American History” (New York: Oxford University Press, 2000, 5 and 7): “Extreme and bizarre religious ideas are so commonplace in American history that it is difficult to speak of them as fringe at all,” and the existence of NRMs is a “persistent theme of American religion.” CAN was oblivious to this fact. In reality, CAN was informed by few if any knowledgeable historical, sociological, theological, or psychological experts.

Slanted information on NRMs was CAN dissemination policy. Several deposed testimonies from CAN leaders illustrate this tendency. For example, CAN employee Marty Butz revealed:

“A. People do contact CAN with their concerns.

Q. And you give them derogatory information about cults, correct?

A. I don’t think “derogatory” is a fair term.

Q. Well, isn’t it a CAN practice to only give derogatory information and not positive information about groups that you consider to be cults?

A. We give a lot of information that’s responsive to the concerns of the individuals.

Q. Well, see, that doesn’t answer my question. My question is: Isn’t it a CAN policy to give derogatory information and specifically not to give positive information about groups that CAN deems cults?

A. Our focus deals with the critical or controversial aspects of these organizations that people have concerns about.

Q. Well, you never provide positive information. You don’t ever seek out positive information to give people about groups you consider to be cults.”

[Butz admitted this was true after some verbal meandering] (“Cynthia Kisser vs. The Chicago Crusader et al.” October 26, 1994. County of Cook, Illinois. Case No. 92. L 08593).

CAN’s Cynthia Kisser (in tortuous prose) admitted that CAN’s policy was to never disseminate information in requested mailed packets about any NRM that could be considered non-threatening or non-destructive: “It’s a general policy for any packet, not necessarily just [on] Scientology… that the information in the packet is information other than that which is provided by the groups [themselves], since that information presumably is readily available to anybody from the group itself. And so the purpose of this is to provide information that’s in the public domain but not already published by the group, you know.”

Kisser’s and CAN’s approach in defining “cults” was laissez-faire, which is to say that they let any inquiries from distraught/worried family members define what was a “destructive cult,” broadening their definitional umbrella. There was no hesitation about establishing “balance” in CAN information, even if the standards seem inconsistent in the same breath, according to the former President of CAN’s Board of Directors: “Most of the information that we receive about groups—actually if we do receive information that has positive information about that group, as well as negative, we don’t try to withhold the positive information… But we don’t endeavor to balance the positive with the negative… I think that our purpose is to collect information that’s been written about an organization. There is plenty of—as counsel said, there’s plenty of positive information that usually people have seen on the organization. They haven’t had access to a balanced view of it. And it’s our job to provide information that gives [a] more critical view of the group.

CAN’s indiscriminate approach to defining and acting against NRMs can be illustrated twice. We provide anecdotal evidence of the rather cavalier attempts to identify “destructive cults” and/or their practices.

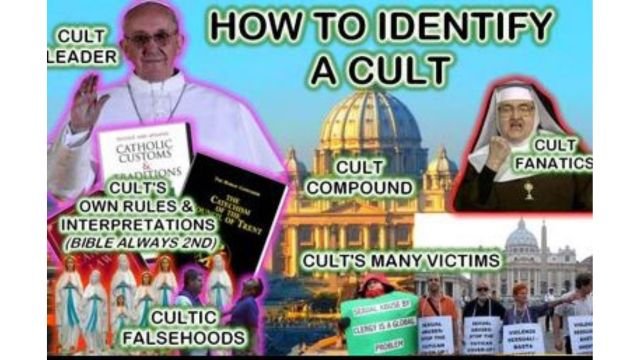

First, in a deposition by CAN’s executive director Cynthia Kisser in which she attempts to deal with the implications of an inclusive definition of cult:

“Q. What’s your definition of cult?

A. Just of a cult?

Q. Yes.

A. It’s—a cult is an organization—an organization can be large or small; size is not the determinant—that has expressive devotion to a leader, principle or idea.

Q. Is the Catholic Church a cult?

A. Under that broad definition, yes.

Q. Is the Democratic Party a cult?

A. Under this definition of cult above, yes.”

Second, in an unpublished manuscript draft deprogrammer Rick Ross interprets charismatic glossolalia as an alleged link to “mind control”: “It seems obvious that the ‘gift’ of tongues is a facet of fundamentalist mind control. It is dehabilitating [sic–there is no such word.] and have [sic] severe side effects. Disassociative [sic] behavior and premature senility have become repeated symptoms” (Excerpt from an unpublished draft of Rick Ross’s book “Mind Control—The Fundamentalist Syndrome,” CAN files).

The most interesting aspect of Ross’ interpretation is that he has little clue as to the difference between a fundamentalist Christian and a charismatic Christian. Likewise,

Cynthia Kisser agreed about glossolalia in analyzing the Christian sect called The Way International: “The Way’s practice of speaking in tongues” is “classic hypnosis” (Joseph Neff, “Adoption Battle Gets New Life from Court,” “News & Observer” [Raleigh, NC], 9/8/1993). But then these sorts of confusions and misunderstandings were mere nuances of little import to deprogrammers and ultimately to CAN.

Anson D. Shupe (1948–2015) was an eminent American sociologist of religions. A professor of Sociology at Indiana-Purdue University in Fort Wayne, Indiana, Shupe published seminal studies of new religious movements, the anti-cult movement, deprogramming, and clergy misconduct and sexual abuse. He also studied domestic violence. Apart from his academic activities, he was also a martial arts expert possessing second degree black belts in Judo and Karate.