CAN’s anti-cult predecessor, the Citizens Freedom Foundation, already got in trouble for its clandestine association with illegal deprogramming.

by Anson D. Shupe (†) and Susan E. Darnell

Article 4 of 10. Read article 1, article 2, and article 3.

It is worth examining several pieces of information on the Cult Awareness Network (CAN)’s predecessor, CFF (Citizens Freedom Foundation), and the brief period of CFF’s transition into CAN since any changes made were plainly cosmetic and, more importantly, CAN continued CFF’s corporate crime policy of facilitating and even encouraging street crime (coercive deprogramming).

CFF had a close but at times ambivalent relations with deprogrammers. Early CFF brochures admired the coercive practice as a necessary, even heroic evil and endorsed it: later, CFF and CAN disassociated the organizations from deprogramming at least on paper. Both groups, however, served as conduits for referrals to deprogrammers.

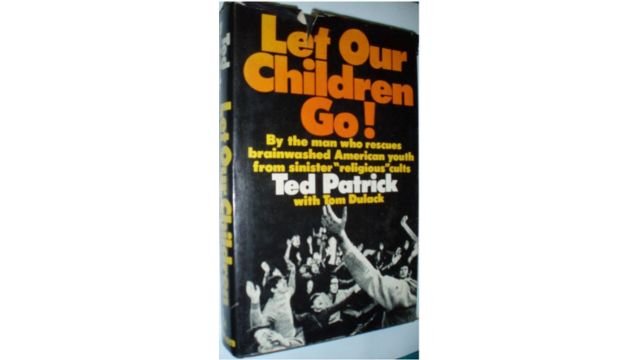

Kent E. Vaughn, a member of the CFF board of directors from 1983-84 and certainly no “cult apologist” (having two adult daughters involved with The Way International), recalled gaining a definite sense that CFF (shortly before it became CAN in the mid-1980s) had a Janus-like public persona very different from its real operations He was made particularly uneasy by deprogrammers’ regular contact with CFF officers: “I was involved in many discussions with other board members about the name change [to CAN]. I believe the general consensus of the board was to change the name to avoid negative references to the organization caused by the arrest of deprogrammers, such as Ted Patrick. Patrick had been affiliated with CFF since it was first started.”

One of those CFF officers was Shirley Landa, CFF president, who participated in a deprogramming. Vaughn found his fellow board members turned deaf ears to his unease, and he began to feel cut off from the decisions made by the organizational leadership. He was disturbed by CFF’s apparent right-wing partisanship and the casual, even irresponsible spending of scarce monies. He also made the board itself uneasy when he brought up the subject of some sort of ethical rein to hold deprogrammers accountable: “At the July 16–17, 1984 New York City board meeting, I got the subject of ethics in counseling put on the agenda. Although I was not fully appraised of CFF–CAN’s activities, I had heard and seen enough to realize that CFF–CAN was connected to involuntary deprogrammers, and that this issue needs to be dealt with. I began the discussion by talking about deprogrammers who were taking large amounts of money from the families of cult members and using violent methods to accomplish the deprogrammings. I told the board that I felt this was very wrong and that we needed to do something about it. After I completed my comments, only I—H—made a comment that supported my position. The rest of the board remained silent. I was aware of deprogrammings, both voluntary and involuntary, that were taking place across the country. I knew the other board members were also aware of these matters. As far as I was aware, there were never any ‘official’ discussions about these issues at prior board meetings. This upset me greatly, and I felt it was a further indicator that there were things going on within the board that I did not know of.”

Vaughn also observed the familiarity with which known coercive deprogrammers “made the rounds” of CFF–CAN conventions, speaking and advertising their services: “I recall that on several occasions at our annual conferences, I would see persons who I knew were active involuntary deprogrammers meeting in small groups with other board members and affiliates. These meetings usually took place during the breaks at the conferences and were often held at a corner table in the lounge at whatever hotel were using. It appeared to me that these activities were deprogrammings of some type being planned. I concluded that the rest of the board members chose to ignore this activity, or pretend that it wasn’t happening, because it was a legally and ethically sensitive issue.”

Vaughn persisted in raising such issues, was warned by a CFF-CAN member that his membership on the board was really a “set up” (his words) and was advised by this person: “After several discussions, she warned me that my life could be in danger if I continued to pursue my investigations into the activities of the board.” This warning was given to him twice. After serving a year and a half of his two-year term on CFF’s board, Vaughn resigned in frustration: “I concluded that anyone who went against the ‘inner clique’ agreements within CAN would be shunned or ostracized.”

In fact, as early as 1980 CFF-IS (Citizens Freedom Foundation Information Service) was troubled internally by its relationship to deprogrammers. Wrote former executive director John Sweeney to several ACM activists: “Scarcely a week goes by without some parent calling and complaining about a deprogrammer. They did not counsel. They did not show up. They overcharged. etc. etc. etc. CFF-IS is an educational foundation. We try to help parents and still educate the public. Deprogramming is not one of our services. Yet we all realize that we are involved in this area of great concern to our members. So like it or not, a problem with deprogramming is a CFF-IS problem.”

That problem continued. Sweeney was dissuaded by the CFF’s lawyer (who must have had some idea of how rapaciously some deprogrammers were behaving) from pursuing an ethical code of behavior for deprogrammers. Sweeney got no further on this count that did Vaughn several years later. The CFF board also rejected the idea. However, Sweeney reports he was greatly disturbed by what he styled (his words) “Quick Pay” methods and maintained that CFF “should not support the money grabbing, amateur kooks that claim to want to help parents but end up ripping them off for thousands of dollars.”

On April 29, 1980, Sweeney wrote to another ACM activist: “We have to continue to stress pre-education as the best antidote to destructive cults. We cannot get in bed with the deprogrammers UNLESS we control the actions of these deprogrammers” (Letter of John M. Sweeney, Jr. to Adrian Greek, April 29, 1980, CAN files).

Sweeney once had a plan to ride herd on the deprogrammers’ worst excesses and simultaneously gain legitimacy for the practice. He wanted to establish an accredited deprogramming facility accepted in both legal and medical worlds, “a facility so renowned that no judge would hesitate issuing an order to have a cultist remanded to that center for a number of weeks. …At least we would make deprogramming and rehab so legitimate that Blue Cross would pick up the bulk of the tab” (mentioned in the same letter). Jokingly, he wrote in a letter to a CFF friend named Allan (n.d.): “On the surface CFF is not involved in deprogramming. Yet if you eliminated every CFF member who had been involved in deprogramming or rehab or rescue work you and I would be the only CFF members left.”

Finally, like Vaughn, Sweeney quit CFF in disgust. Recalling the circumstances of his resignation, he made mention of another disturbing pattern in CFF-endorsed activities: “Many deprogrammers had sex with their victims and used drugs during the deprogrammings.” (More on these actions later in the series.)

Anson D. Shupe (1948–2015) was an eminent American sociologist of religions. A professor of Sociology at Indiana-Purdue University in Fort Wayne, Indiana, Shupe published seminal studies of new religious movements, the anti-cult movement, deprogramming, and clergy misconduct and sexual abuse. He also studied domestic violence. Apart from his academic activities, he was also a martial arts expert possessing second degree black belts in Judo and Karate.