The Palestinian Muslim Brotherhood was accused of having wasted twenty years in building mosques rather than organizing terrorist attacks. But the mosques prepared the future success of Hamas.

by Massimo Introvigne

Article 3 of 8. Read article 1 and article 2.

In the previous article of this series, we presented the division in Palestine between the ostensibly secular Fatah and the Muslim Brotherhood, while noting that some of the founders of Fatah had been members of the Brotherhood themselves. In the years immediately following the split, Fatah gained members at the expense of the Muslim Brotherhood, also as a result of the campaign unleashed against the latter in Egypt by President Nasser, which did not fail to have repercussions in Palestine.

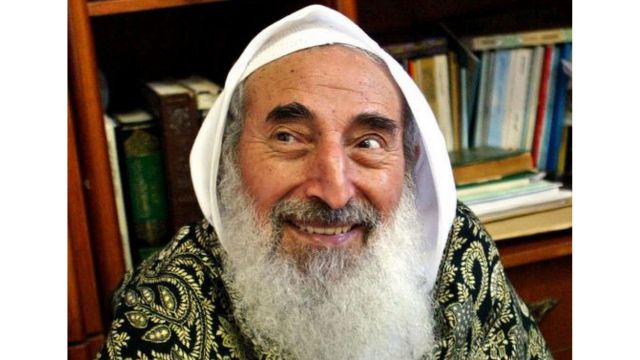

In 1966, Shaykh Ahmad Is’mail Yassin, who was emerging as the main leader of the Palestinian Brotherhood, was arrested by the Egyptian government, and released after a brief detention. In 1967, with the Six-Day War, the situation changed. The Palestinian Muslim Brotherhood took part in the years 1968–1970 in military operations launched against Israel by Jordan, under pressure from the Brothers of other countries (including from Sudan) and in collaboration with Fatah.

The Brotherhood, however, presented the Arab defeat as a chastisement by God upon rulers hostile to them, and reintroduced with renewed conviction the idea that a patient work of Islamization of society was necessary. The movements gathered in the PLO, by contrast, remained convinced of the need for a genuinely national and Palestinian armed struggle that would not depend on the support of foreign armies. Cooperation between the Muslim Brotherhood and the PLO became increasingly difficult, since openly Marxist components emerged in the PLO that proclaimed themselves atheistic and openly mocked religion, much to the scandal of Yassin and the Brothers. The latter will later be accused of having essentially wasted almost two decades, from 1967 to 1987, by abstaining from armed struggle .

However, these were years in which the Muslim Brothers achieved conspicuous results in their project of re-Islamization of Palestinian society. Between 1967 and 1987, mosques increased from 400 to 750 in the West Bank, and from 200 to 600 in the Gaza Strip. The Brothers also controlled, since its founding in 1978, the majority of students at the Islamic University of Gaza, where they consistently won student elections. They had a major presence in other universities, high schools, the sport world, and private clinics. This activity grew until the early 1980s with the tacit consent of Israel, which initially saw the Muslim Brotherhood as an interesting thorn in the side of Arafat and the PLO, and an organization that was primarily concerned with religion and culture and posed little danger from the point of view of armed resistance.

In the early 1980s, however, the organization founded by Yassin in 1973 to coordinate various Brotherhood activities, the Islamic Center (al-Mujamma al-Islami), endowed itself with a more or less clandestine military branch (al-Mujahadoun al-Falestinioun, the “Warriors of Palestine”). The Israeli services initially believed that it was merely a parallel police force charged with cracking down on public sinners (prostitutes, alcoholics, shopkeepers selling pornographic material) in the name of shari’a and settling some scores with rival organizations. When, however, among the sinners to be punished the organization includes collaborationists who openly or clandestinely sided with Israel, and started circulating documents discussing the possibility of a revival of the armed struggle, the Israelis arrested Yassin in 1984 and sentenced him to thirteen years in prison. He was freed in 1985 as a result of a prisoner exchange with the independent insurgent group of Ahmad Jibril (1935–2021).

These episodes reveal a reversal of perspective with respect to the fifteen years following the Six-Day War of 1967. The Muslim Brotherhood and Yassin had criticized Fatah and the PLO for prematurely setting out on the path of arms before society had been Islamized through patient educational and cultural work. Now, they were switching to armed struggle themselves, and were even ready to criticize the PLO from more radical positions. For some, this was a belated admission after nearly thirty years that the Muslim Brothers had been wrong in rejecting the al-Wazir Memorandum and alienating themselves from the armed struggle. The Brothers countered that this was a simple application of the principle of gradualism dear to their founder Hassan al-Banna. The very success achieved over thirty years of propaganda, construction of mosques, and educational and cultural activities had made it possible, in a changed international climate characterized by a strong resurgence of armed Islamic radicalism in several countries, to move on (or return) to the stage of armed resistance.

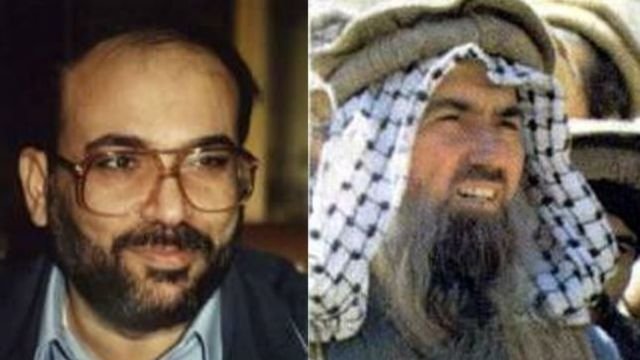

The Palestinian Brotherhood was returning to the armed struggle at a time when the Egyptian Brotherhood seemed to have abandoned it in favor of the work of Islamization through the building of civil society institutions, of which Yassin in Palestine himself had been a pioneer. Paradoxically, the two developments are not unrelated to each other. Since the late 19th century, many young Palestinians had studied in Egyptian universities. There the Muslim Brotherhood had influenced one generation. There, a later generation encountered in the 1970s and 1980s the movements that split from the Muslim Brotherhood after its neo-traditionalist choice that followed the execution of Qutb. Some in this generation will later flow into the Egyptian Islamic Jihad and other groups that were part of the al-Qa’ida network led by Osama bin Laden (1957–2011). In 1980, upon returning to Palestine, some of these students left the Brotherhood organization (as their Egyptian inspirers had done) and founded the Palestinian Islamic Jihad, a group led by Fathi Shaqaqi (1951–1995) that will be noted for its radicalism, It succeeded in taking some members away from the Muslim Brotherhood.

Another form of radicalism that was emerging in Palestine was that of Shaykh Abdullah Azzam (1941–1989). Azzam was born in 1941 in Seelet al-Hartiyeh, in the West Bank, and attended various Jordanian schools before receiving an academic degree in Islamic Law from Damascus University in 1966, followed in 1973 (when he was already a professor at the University of Jordan in Amman) by a doctorate from al-Azhar University in Cairo. Azzam participated in PLO activities but did not appreciate its nationalism. In search of what he called “true Islam,” he emigrated to Saudi Arabia in 1976 and became a professor at King Abdul Aziz University, where he taught an Islamic radicalism with strong millenarian overtones. Beginning in 1979, he alternated between academic work and guerrilla warfare in Afghanistan. It was an adventure for which he aroused the enthusiasm of several of his students, including Osama bin Laden. The future leader of al-Qa’ida became his spiritual son and heir although, when Azzam and two of his sons were killed in an attack in Peshawar, Pakistan, in 1989, several intelligence services suspected the hand of bin Laden, now jealous of his old mentor’s popularity.

In the 1980s, the émigré Azzam became a point of reference for many young Palestinian radicals, though not for the Islamic Jihad. For Azzam, the Palestinian issue was one of the fronts on which the Muslim umma was engaged in its struggle against the worldwide conspiracy that opposed Islam. Other issues were equally important. In fact, Azzam prioritized the Afghan issue, which seemed to him to offer better prospects for an immediate victory. The Palestinian Islamic Jihad, on the other hand, believed that, for theological rather than political reasons, the Palestinian issue should retain priority over any other Islamic problem, and on this point it separated itself from Azzam.

However, Azzam and the Islamic Jihad were united in their criticism of what was then the neo-traditionalism of the Muslim Brothers. Yassin’s reaction was different from that of the Egyptian Brotherhood. While the latter condemned terrorism, Yassin sought to avoid the hemorrhage brought about by Islamic Jihad and Azzam’s disciples by competing with them on his own ground in a process that led to the founding of Hamas.

The Muslim Brotherhood always pursued different strategies according to different national situations. In Palestine, Yassin believed that the foreign occupation, the attitude of the PLO, and the strength achieved by the Brotherhood movement created a different situation from that in Egypt. The Palestinian context justified the choice of armed struggle, which had always been present in the range of options considered by al-Banna well before Qutb tried to elevate it to the movement’s unique strategy.

Massimo Introvigne (born June 14, 1955 in Rome) is an Italian sociologist of religions. He is the founder and managing director of the Center for Studies on New Religions (CESNUR), an international network of scholars who study new religious movements. Introvigne is the author of some 70 books and more than 100 articles in the field of sociology of religion. He was the main author of the Enciclopedia delle religioni in Italia (Encyclopedia of Religions in Italy). He is a member of the editorial board for the Interdisciplinary Journal of Research on Religion and of the executive board of University of California Press’ Nova Religio. From January 5 to December 31, 2011, he has served as the “Representative on combating racism, xenophobia and discrimination, with a special focus on discrimination against Christians and members of other religions” of the Organization for Security and Co-operation in Europe (OSCE). From 2012 to 2015 he served as chairperson of the Observatory of Religious Liberty, instituted by the Italian Ministry of Foreign Affairs in order to monitor problems of religious liberty on a worldwide scale.