Threats by extremist Tehreek-e-Labbaik made it impossible to release in Pakistan what critics hailed as one of the best Pakistani movies of recent years.

by Massimo Introvigne

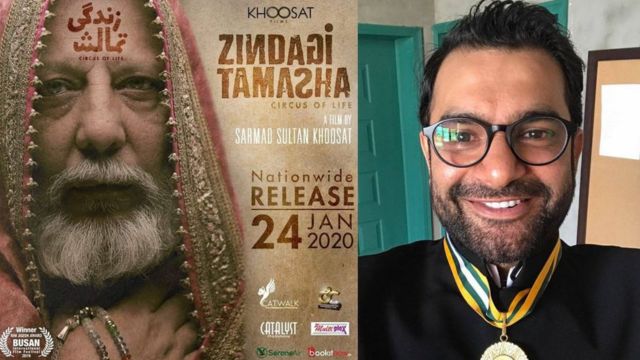

In 2020, “Zindagi Tamasha,” a film by acclaimed Pakistani director Sarmad Khoosat, was the Pakistani Oscar nominee for the 93rd Academy Awards. Yet, Pakistanis cannot see it in theaters. Last month, after years of failed negotiations and court cases, the director gave up and decided to release the film online only. He said it would not be the same as seeing it on large screens in theaters, but at least Pakistani citizens (and anybody else) can finally access it.

Basically, this is yet another instance in which the authorities are scared enough by the extremist movement Tehreek-e-Labbaik Pakistan, which had proved that it is capable of paralyzing the country with long riots, that they decide to humor it rather than risking a confrontation. The government surrendered to Tehreek-e-Labbaik on the admittedly more deadly matter of a stricter enforcement of anti-blasphemy laws. It is not surprising that it surrenders again when “only” a film is under attack.

Why the attack against “Zindagi Tamasha”? The beautiful film, whose title has been translated in English as “Circus of Life,” is about an elderly man, who is a pious Sunni Muslim and a respected real estate agent. One day, he attends a wedding and decides to engage in a humorous dance. A guest captures the dance on video and uploads it on social media.

Netizens start attacking the man as “effeminate,” claiming he is probably gay (he is not, as his bedridden wife can testify). The video goes viral and is even discussed on television. The old man’s life and career are ruined. He is attacked and threatened by local fundamentalists, and shunned even by relatives and friends.

Although no movement is named, fundamentalists such as the leaders of Tehreek-e-Labbaik can easily feel targeted. They do not understand that the film is not really about extremist Islam. It is about the obnoxious power of social media haters, who can destroy a life and a reputation, a problem that does not exist in Pakistan only.

What is peculiar to Pakistan, however, as a few independent voices have bravely noted, is that art and culture are not free, no matter how high is their quality and how respectful they are of the Islam (as the film is). Groups such as Tehreek-e-Labbaik are officially condemned, yet in fact they keep an entire country hostage, and the government is too weak to resist them.

Massimo Introvigne (born June 14, 1955 in Rome) is an Italian sociologist of religions. He is the founder and managing director of the Center for Studies on New Religions (CESNUR), an international network of scholars who study new religious movements. Introvigne is the author of some 70 books and more than 100 articles in the field of sociology of religion. He was the main author of the Enciclopedia delle religioni in Italia (Encyclopedia of Religions in Italy). He is a member of the editorial board for the Interdisciplinary Journal of Research on Religion and of the executive board of University of California Press’ Nova Religio. From January 5 to December 31, 2011, he has served as the “Representative on combating racism, xenophobia and discrimination, with a special focus on discrimination against Christians and members of other religions” of the Organization for Security and Co-operation in Europe (OSCE). From 2012 to 2015 he served as chairperson of the Observatory of Religious Liberty, instituted by the Italian Ministry of Foreign Affairs in order to monitor problems of religious liberty on a worldwide scale.